This article is part one of a two-part series on using color theory to deconstruct race. Part two can be seen here.

Race is something students recognize from their earliest ages. They learn right away that they belong to a certain race and that their race is completely different than all others. Society has used different colors to categorize people with labels such as black, white, yellow, red, and brown. The theory I challenge students with each year is this: no human being is actually white, black, yellow, or red, but we are all variations of brown. In color theory terms, all human skin colors are different hues and values of brown.

The Hues and Values of Brown Theory

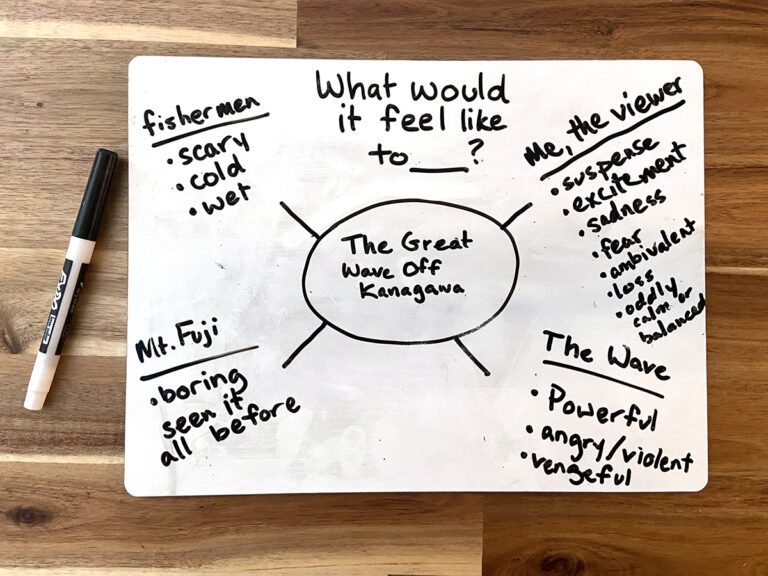

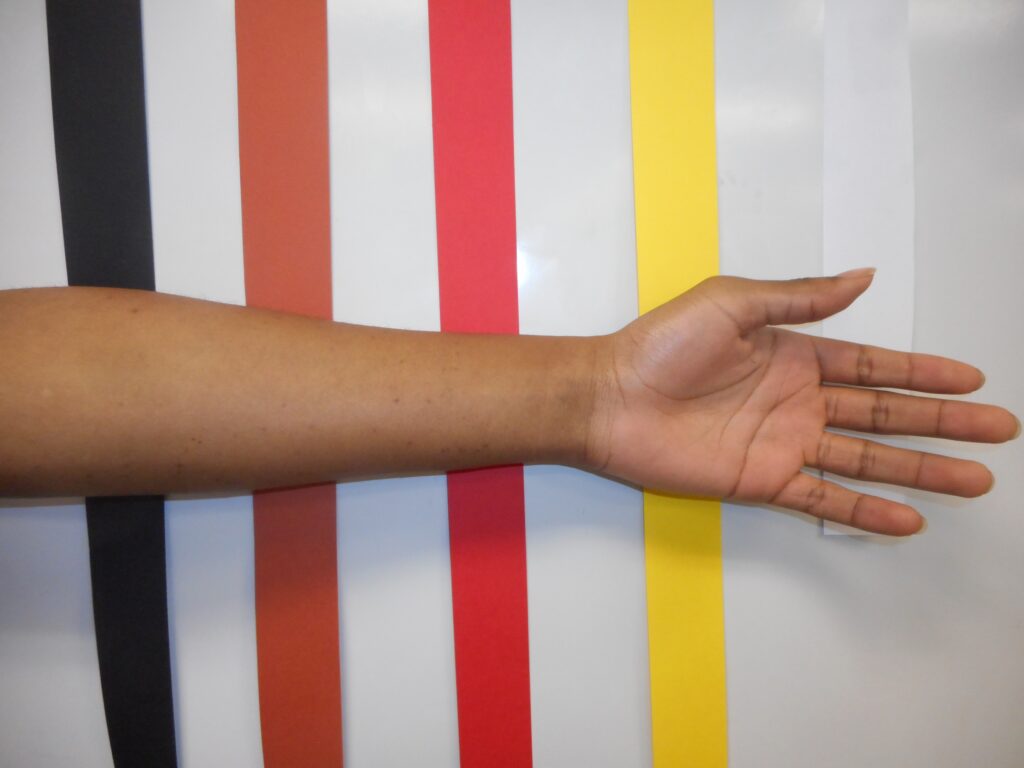

I explain this theory in my classroom by breaking it up into two parts: the introduction, and matching skin colors with paint. Today’s article will focus on the introduction, and tomorrow’s article will describe how we mix paint. The introduction begins like this: there are five pieces of colored paper at the front of the class, one for each of the racial color categories. Students are asked to name each of these colors together. A class consensus on each color name is immediate.

I then ask students if there are any black or white students in the room. Many hands shoot up. I politely invite them to compare their skin color to the colors on the board that we identified as black and white. Once one or two volunteers agree to compare their skin to each color, it is obvious their skin colors and the actual agreed upon colors do not match up.

At this point, I present my theory to students and challenge them to try and disprove it. I say, “This is my theory on human skin color. I have tested it with students for over ten years and not a single person has been able to disprove it. Nobody is black, nor white, nor yellow, nor red. We are all different hues and values of brown.”

Examining the Spectrum of Skin Color

Students will not feel comfortable at first when their identities are confronted. There can be instant responses like, “I know this person who is literally black!” or “What about albinos?” To address the exceptions students will eagerly present, an evidence-based slideshow accompanies the next piece of the discussion. The slideshow contains images of the darkest skinned and lightest skinned people found through a Google image search. Those images are examined. What students first need to know are the definitions of black and white. I ask my classes if there is any color darker than black, and they respond that there is not. The same question is posed if there are colors lighter than white, and the same answer is given. The essential definition of white and black is that they are the extremities of light and dark. No color is lighter than white, and no color is darker than black.

Now it is time for the shocker. When looking at people with the darkest skin colors, compare their skin color to their hair color. Which is darker, the skin or the hair? The hair will be darker every time. By definition, if the hair is darker than the skin, the skin cannot be black. The same test works for light skin. Compare the whites of the eyes or the color of the teeth to the skin…or hold up a piece of paper next to the image. Is there a color that is lighter than the skin? If there is, by definition, that skin is not white.

When comparing people of Asian and Native American descent to the racial category colors of yellow and red, the fallacy of racial categorization is even clearer. No matter which image you use, there are no human skin colors that match yellow. There are no skin colors that match red. This lesson presents a great opportunity to apply color theory terms such as shade, tint, hue, tone, and value. While people do have skin colors with varying hues and values, the color that encompasses all human skin is brown.

The final test is to ask the class if anyone in the room has ever been classified as brown. Often times several students will raise a hand. A volunteer can come up and compare their skin color with a brown piece of construction paper or a painting of some kind. Usually, it is easiest for students to notice that the brown is the best representative of human skin color. Human skin colors represent the entire spectrum of brown, but brown is our shared heritage.

Critical Questioning

After examining the racial color categories that have confined us for centuries, there are more questions that can be asked. For example, challenge your classes to contemplate why this system of color categories exists. Who benefits from the population dividing itself into color categories? What are the effects of seeing differences between groups before seeing any similarities?

Even though the range of human skin colors is a vast spectrum from dark to light, skin itself does not quite reach the polar opposites. There is true power to exploit from this insight. We have learned throughout time that people belong to color groups such as black, white, yellow, red, and brown. These colors have nothing in common with each other. Black and white are complete opposites. Yellow and red are primary colors and share absolutely no pigment in common. The only color that actually can be made by mixing black, yellow, red, and white is brown.

While there is importance to identify culturally or through experience with a racial group, it is equally important to dissolve the illusion that helps keep us separated. If we are able to see each other as different hues and values from a common brown, perhaps we could help cultivate more empathy and compassion in our students.

Part two of this series details how students can use the color mixing process to match their skin color, making the spectrum of brown even more obvious and illuminated.

What issues or challenges come up when thinking about discussing racial topics in art class?

What projects or lessons have you implemented that examine race?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.