The following article is written by an art educator working in a district that supports marginalized members of the community. The article is written from that experiential lens. We recognize that it may not be safe or permissible to engage in these discussions at your school. We encourage you to keep your safety, your students’ safety, your district regulations, and the parents in your community in mind at all times.

Many marginalized students share a similar experience entering a new classroom: they walk in, scan their surroundings, cautiously interact with new people, and assess if you and your room are a safe space. Whether it’s from their own personal experiences and/or societal norms, some students feel their identity is not welcome in your art room. As student populations shift in our country at a much more rapid rate than the teaching population, understanding marginalized identities and implementing teaching strategies to support them in the classroom is critical to being a good teacher.

What is a marginalized identity?

The first step to supporting students is understanding your marginalized students. A student’s identity is made up of several factors and has many layers. The extent to which a student is impacted by each of their identities also varies based on their lived experience.

According to Charter For Compassion, a marginalized identity is anyone who feels or is, “underserved, disregarded, ostracized, harassed, persecuted, or sidelined in the community.” Possible groups include but are not limited to:

- Immigrants, refugees, and migrants

- Women and girls

- Victims of human trafficking

- People struggling with mental illness

- Children and youth

- People of differing sexual orientations (LGBTQ+ community)

- People of differing religions

- People with developmental delays

- Those with a physical disability

- Incarcerated people (and their families)

- People released from incarceration

- People of low socioeconomic status

- Unemployed people

- People of a particular ethnicity/country of origin

- People with a differing political orientation

What can teachers do?

Being nice isn’t enough. Students deserve a teacher who is actively honoring their identity in the classroom. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs illustrates the importance of students feeling safe, physiologically and physically, before they can learn and reach their potential. What’s required for personal safety is dependent on the person. But to get you started, here is a list of common approaches you can immediately implement in your classroom.

Hang classroom visuals.

One of the easiest and most technical approaches is to fill your space with imagery and messaging supportive of the identities of your students, particularly your marginalized students. Students develop their first impression as they look around your classroom and wait for you to begin class. Before you even have a chance to speak to the class, students are internalizing the messaging in your room.

So, help their first impression be a supportive one by hanging posters and graphics that affirm their identity and send the right message. Students can connect with images of artists, subject matter, historical images, or images of support like the Hate Has No Home Here graphics. Scan your room and ask, “Can each of my students connect personally with something in this room? What messages do the images in my room send and to whom?”

Use supportive language.

Words matter. The words you use and don’t use with students play a critical role in supporting their identity. While you might initially think about direct conversations with students, marginalized students can be equally impacted when they overhear a teacher’s comment to another student. Or, if they observe no action by the teacher for student comments. Help students by being aware and informed of the various sub-groups students can represent. Be able to identify stereotypical or biased imagery in student work or reference materials and address them accordingly. Have an understanding of their culture, so you use appropriate language and terminology.

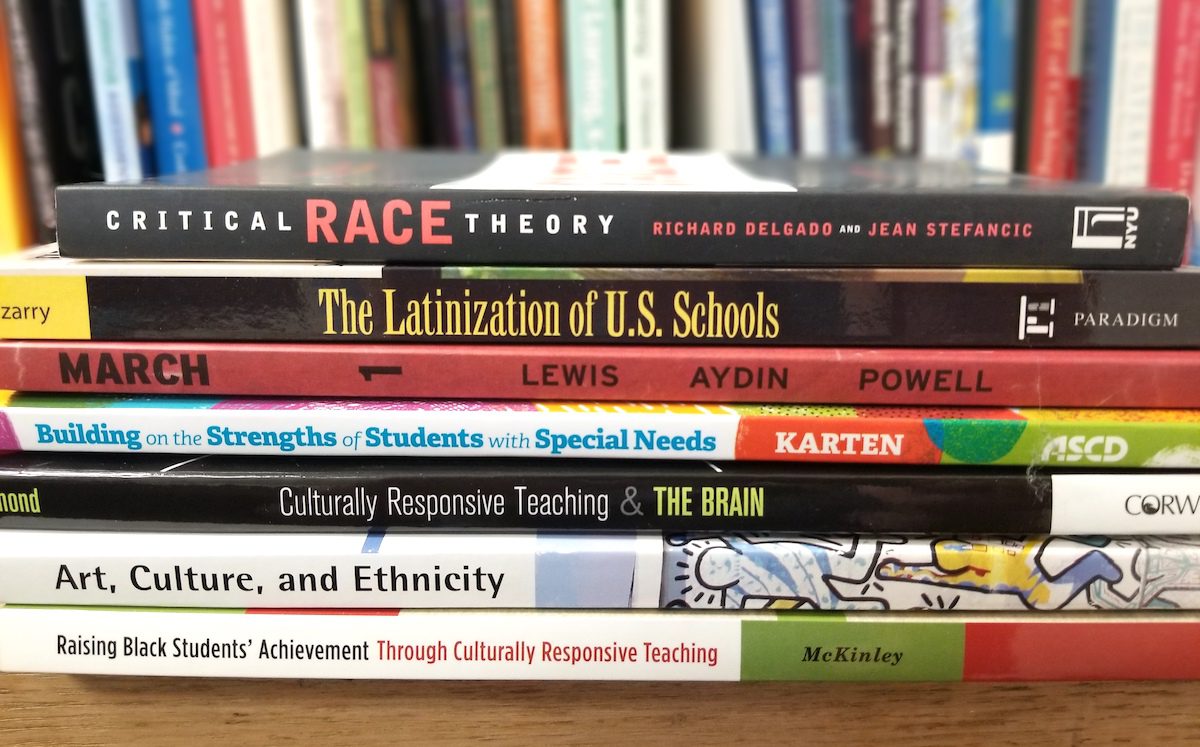

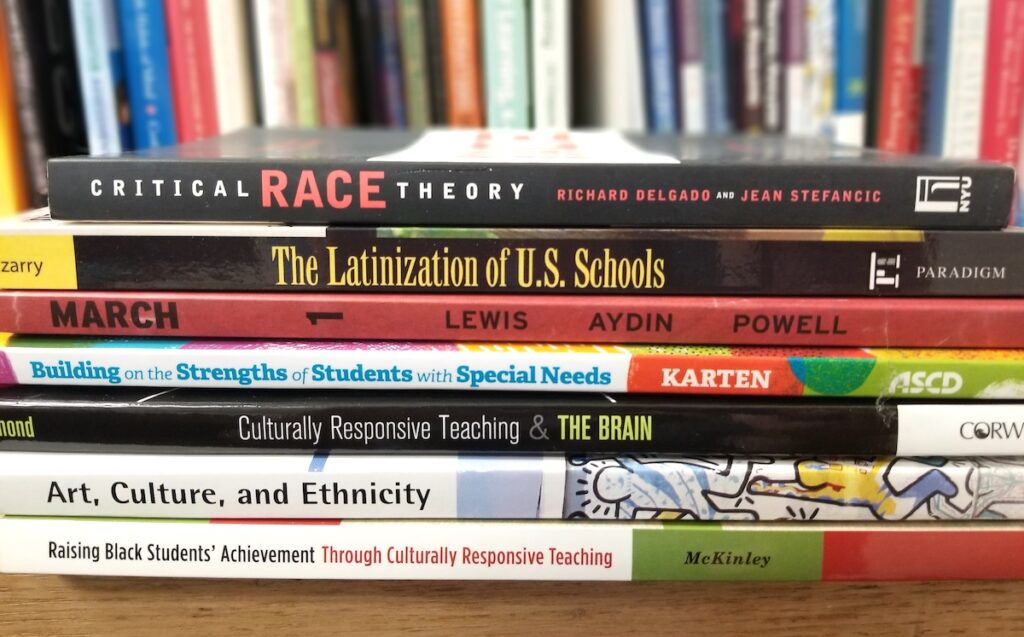

Provide a culturally relevant curriculum.

Honoring and acknowledging the identities of your students is a year-long responsibility and not only reserved for identified months like Black History Month or Pride Month. Use your curriculum to help all students see themselves in art by introducing them to a diverse group of artists and artwork. Provide choice and options for prompts with all of your projects to increase engagement and help as many students as possible connect with their art. When you limit students to one prompt, you’re assuming every student has a positive connection and you might be unaware of potential triggers. For example, the concept of memories can sound positive, but not for students with trauma.

To give you a head start, check out these articles for a list of Black Female Artists and LGBTQ+ Artists you should know.

Remove existing barriers.

Rather than focusing on the students in your room, consider who is missing and try to identify potential barriers blocking their access. One approach is to compare how your art student population aligns with the rest of the building and identify any gaps. You could also review any policies or practices to see how those could be unintentionally blocking access for students. For example, lab or material fees could be impacting your students with financial struggles. Or if art is scheduled at the same time as reading or a support class, those students are now prevented access. Once you have recognized a potential barrier, strategize the best approach for change and include supporting data for your administration.

Make the art room fully accessible.

Proactively making your classroom accessible and inclusive for students with special needs can send a more welcoming message to a whole population of students. Start by making sure your physical space is open and free of clutter to help students with physical challenges better navigate your room. Then, review your curriculum and develop new projects through a lens of universal design, which includes common accommodations in the lesson construction. Once you’re prepped and ready, meet with your administrator and a special education representative to share your enthusiasm and preparations for teaching all students.

The art room should be a safe and inclusive space for all students. Unfortunately, this is not the case for many students as they enter your room with a lifetime of messaging and experiences that say their identity is not welcome. However, intentionally supporting your students by honoring who they are can help your art room become a safe space. As you implement these new ideas, continue to seek out additional resources and opportunities to learn about the cultures of the various sub-groups represented in your room to help you be a better teacher for your students.

How can schools help teachers better understand the identities of their students?

What resources exist to help teachers learn about new artists from other cultures?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.