As art educators, there are many ways to define and conduct research. From initial investigations for an upcoming lesson to diving deeper into our artistic processes and then to compose a formal report of classroom findings. There are a variety of ways information and data gathering can inform practice.

Research is essential for your own classroom, as well as the field at large.

Whether you are conducting an informal study in your classroom as you look at assessment data, facilitating a self-study on artistic growth, or completing a culminating research project for a master’s degree program, here are eight tips and tricks to help you stay organized, motivated, and successful from experienced researchers.

1. Start early.

Say you need to complete a project for a program of study, or you just have the “researcher itch,” starting the process early is key. You may not have an ironed-out topic or specific research questions in mind, and that’s okay! Begin with your timeline.

It is often helpful to work backward. When do you want to complete your research? Do you want to present at a future conference or submit a paper for a special issue of your favorite publication? Identify a target date for your final work, and then set reasonable targets along the way — budget plenty of time for each phase of your work, including initial exploration and state-of-the-union-research. Then, dive into the web at large. Read about topics of interest to you. Attend related professional development opportunities. Document your learning each step of the way.

Download Your Research Timeline

2. Set a focus.

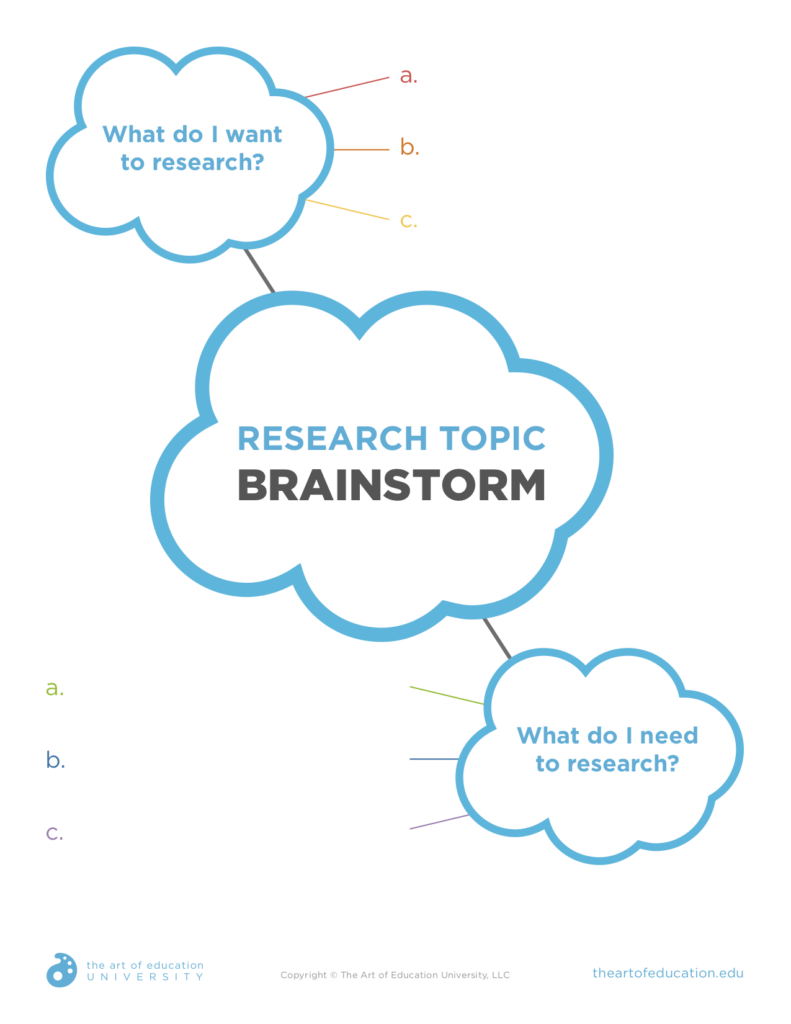

As you dive headfirst into your general area, you will start to see patterns in knowledge. You may even begin to gravitate toward specific voices in the field. After reading a powerful publication, you might find yourself looking to the reference listing for more reading material on the topic. These are signs you are getting closer to setting a focus for your research and establishing some research questions. As you approach this phase of your research, consider the following:

- What do you want to know?

- What do you need to know?

Download this Research Topic Brainstorm

What you want to know may vary from your school’s initiatives or other pressures you might be feeling from your community. If you still aren’t sure what your research focus should be, try answering these two questions:

- Do you want to fill a gap in the literature?

- Do you want to add to current knowledge?

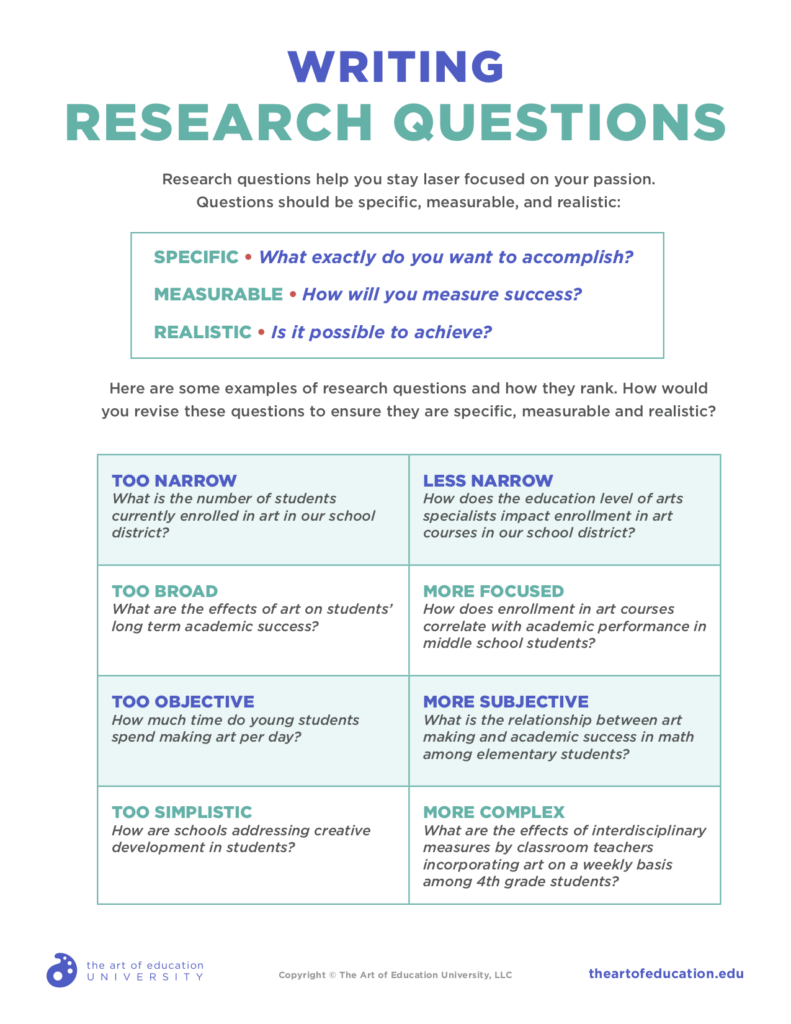

Many researchers work toward presenting new knowledge to their respected communities, while others find joy in contributing additional perspective on current insights. Regardless of your end-game, you want to set a focus that you are passionate about and won’t tire of researching. Research questions help you stay laser-focused on your passion.

Download Writing Research Questions

Voices from the field

- Dr. Alexandra Overby, “The power of asking questions is the catalyst for engaging research.”

- Dr. Wynita Harmon, “It’s important that you are passionate about your research because you are going to live and breathe that information for a long time. You are going to become an expert because you will have read numerous books and articles over your topic.”

- Dr. Sarah Hale Keuseman, “It’s important that you are passionate about your research. That’s why I explore topics that are close-to-home for me, like topics that impact my teaching, my creation process, or my everyday life.”

3. Work out organizational systems.

You’ve set your focus. You have specific, measurable, and realistic research questions. You are ready to dive deeper into your research! Whether you are looking at what others have done in the past, adapting their strategies in your classroom and reflecting, or collecting data from an established pool of consenting participants, you want to set organizational structures early on.

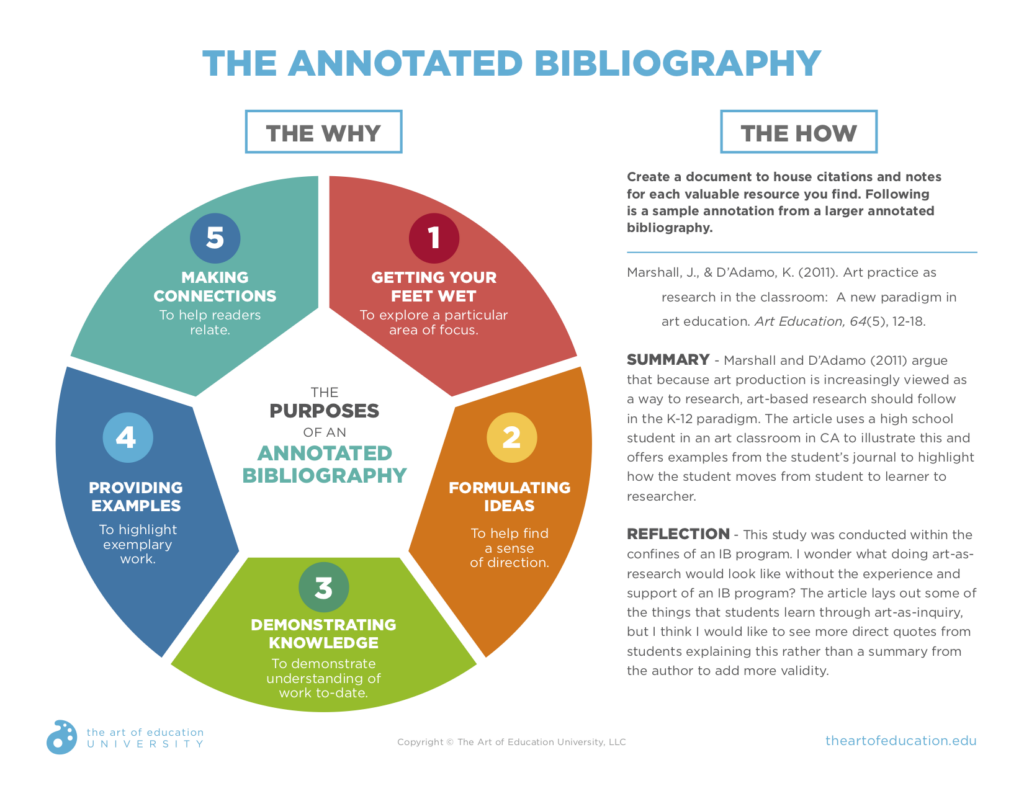

Regardless of your end goals, you will be looking at a lot of work-related to your topic of interest. It is essential to document internet and library searches, so you can retrieve content when needed. Following is a helpful resource when starting an annotated bibliography of your own.

Download The Annotated Bibliography

As you think about organizing reading material, consider how those same systems can support you when organizing and filing data. Regardless of the type and format of data you are collecting, consider your organization. Clearly label all files from day one of your research. This will save you time and anguish in the long-term.

Voices from the field

- Dr. Sarah Hale Keuseman, “My #1 piece of advice is to STAY ORGANIZED! Save your searches, keep detailed notes!”

4. Work in productive spaces.

It is important to identify productive places where you can work on your research. I am not talking about where you collect your data, or where you might collaborate with other researchers. I am referring to the places you sit, think, reflect, write, re-write, and write some more.

During my own doctoral research, I had many conversations with peers who reported that every time they sat down to work on their research they would be overcome with the insatiable desire to clean, usually their refrigerator. What may seem like a downright silly response can be a very natural reaction to prolonged work. Know yourself and your best working conditions, and do your best to minimize distractions.

Voices from the field

- Dr. Christine Woywod Veettil, “My favorite place for reading, writing, and diving into others’ research is in a hotel room. No joke! When I am separated from my regular demands and get to be around exciting people and ideas, I want to run with that momentum!”

- Dr. Wynita Harmon, “During my dissertation process, my ideal working space was a bit of organized chaos. You could always count on seeing the APA manual as well as stacks of articles labeled with sticky notes that correlated to themes in my paper.”

- Dr. Alexandra Overby, “My ideal working space is one that has a big table to lay out all my files and images as well as a blank wall to post and organize my thoughts. This ideal space would not need to be cleaned up at the end of my working session to be used for another purpose.”

5. Prioritize your research and tasks.

The first part of prioritizing seems simple enough, but it can be quite difficult. That is prioritizing your research at large. How often have you started a project, only to fall victim to distraction? We’ve all been there at one point or another. It’s okay! However, when you find the perfect topic you are passionate about, with buy-in from key supporters, you must follow through. Defend and protect your research time. Be sure to share your research agenda with colleagues, superiors, friends, and family, so they understand and respect your goals.

Strategically prioritize the tasks you don’t want to do early on. For example, you might need permission to observe or collect particular data, especially when working with children in public school settings. Some requirements and documentation can be lengthy and time-consuming. Do these types of tasks first so you can jump into your research and data collection.

Voices from the field

- Dr. Alexandra Overby, “In my busy life, I have to prioritize time to do any research. This means I have to plan a week or two ahead of time to ensure that I meet all my responsibilities at work and home, set up a playdate for my children, and limit distractions during my research time (silence my phone, close out all email apps, etc.).”

- Dr. Rachael Ayers-Arnone, “I like research (mostly). It is like a scavenger hunt. It is exciting to find interesting things to work into my writing. The hunt is made more difficult, however, if there is little to no research directly related to my topic. Figuring out how to diversify what I search for was one of the hardest parts of the process.”

6. Practice self-care.

You’ve selected a research agenda you are passionate about. You’ve communicated your goals with those around you. Once immersed in your work, it is easy to get sucked in. Soon you might feel like every fleeting moment is dedicated to research. You might even start dreaming about data. This might be a sign you need a brief break from your work. When sitting down to your research calendar, work in strategic pauses from your project. Timeframes vary from person to person. Sometimes I need just an afternoon away from the computer. Sometimes I need a day or two to do something entirely different. This helps me recharge and also come back to the research with a fresh lens. Listen to your body. Stay in-tune with your brain and carefully watch your response to stress. Your work can afford some time away on occasion, especially if it leads to stronger output in the long run.

7. Connect with others.

No matter what phase of research you are in, it is crucial to ask for outside insight and opinion. As Dr. Sarah Hale Keuseman puts it, “Research can be very isolating. This is why it’s so important to develop connections with those who are going through the same process as you.”

When you are in the middle of research, it is easy to immerse yourself in the mission. You have, hopefully, selected a topic you are passionate about investigating. That being said, sometimes you aren’t the best person to objectively critique your own work. I have a group of colleagues and fellow art education researchers I can lean on to share evolving work. I also make it a point to share with those outside of the field entirely. While it might pain him to do so, my husband is an excellent set of eyes, as well as my mother. These two read for comprehension, while others in the art education field read for content.

Voices from the field

- Dr. Rachael Ayers-Arnone, “I had others read my research often throughout the process. I have a learning disability. Part of my disability is that I cannot read something as long as my dissertation (over 300 pages) and know if it is coherent. I had fellow teachers read sections and advise me. My advising professor also read my work often. I sent her a chapter at a time. I also hired a former teacher from my school to edit my work. She had seen first-hand many of the projects I wrote about. She also understood research, the need for me to state why I was doing what I was doing, and back it up with other’s research.”

- Dr. Christine Woywod Veettil, “My #1 piece of advice for researchers just starting out is to work with a strong mentor: someone with whom you work well, who is invested in your success, and who will to show you what kinds of things you can and should do as a researcher so others can benefit from your work. Bring your best effort and energy to the situation, and when it’s time, do your part to mentor others! “

- Dr. Alexandra Overby, “Seek out opportunities to ask peers questions! Many times I find myself thinking too narrowly about a particular topic, and talking with my peers helps me open my perspective up to other solutions.”

8. Celebrate regularly.

One of my favorite teachers of all time called exams “celebrations of learning.” This was coming from a statistics professor during my Ph.D. program at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. That phrase has followed me ever since. Each class for this instructor was a success if we asked meaningful questions and sought powerful answers. If each class was a party, our final exam was a relative gala. While we didn’t break out the red carpet attire for summative assessments, we certainly celebrated progress. This transformed the learning experience.

Celebrate regularly when it comes to your research endeavors. Work little celebrations into your research calendar. You’ve collected and coded all of your data! That earns you a latte at your local coffee shop. Then, back at it. It can be something big or small—you choose.

Then, upon completion of your work, share your findings with your community. This could include presenting to the art teachers in your district or leading a session at your state or national conference. You might find yourself writing an article for a local or even national publication. Perhaps your work leads you to create a display of work. Celebrate your learning meaningful ways.

Voices from the field

- Dr. Alexandra Overby, “Share your work with peers at professional development days or conferences. A personal goal is to get back into publishing my work for a larger audience.”

After you relish in your fine work, consider, what’s next? The art world needs ongoing research! Hopefully, these tips and tricks help you get started and stay motivated when it comes to your research interests.

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.