One step to creating an inclusive curriculum is to look at cultural appropriation in the art classroom. It’s no surprise that artists create what we know; for centuries, humans reflect what we see, then combine, modify, adapt, and borrow. However, when it comes to reflecting cultures other than our own, we must be intentional and sensitive to the cultural contexts of colors, symbols, and techniques we use.

As art educators, not only do we need to look carefully at how our students are appropriating cultures in their own artwork, but we must also reflect on how we might unintentionally be teaching students through cultural appropriation.

Artistic Appropriation vs. Cultural Appropriation

As art teachers, we talk about appropriation all the time. Appropriation is when an artist takes a well-known image and uses it specifically for the social construct it carries to make a statement in a new way.

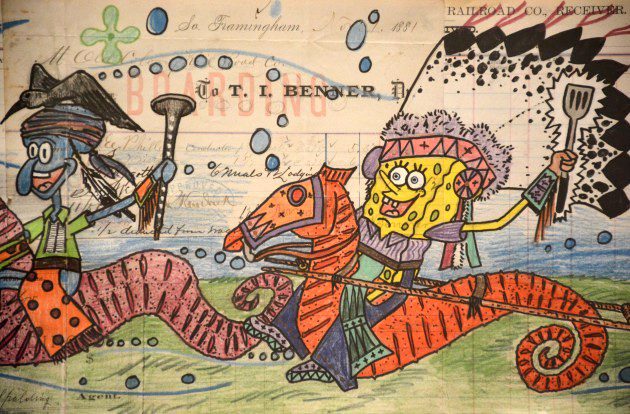

For example, when a student looks at Spongebob and directly replicates Spongebob in all his glorious cartoon nuances, your student is copying. When a student looks at Spongebob and creates artwork about sea life in a cartoon style, your student is using Spongebob as inspiration. When your student looks at Spongebob, creates a new subject that looks similar to Spongebob, is perhaps an olive color instead of bright yellow, manipulates the character in other manners, and creates a polluted environment, your student is appropriating Spongebob for the happy-go-lucky context we all know and love to tell a story about sea pollution. Just Googling “Spongebob Appropriation” brings up a myriad of playful examples.

Cultural appropriation, according to Lexico.com is, “The unacknowledged or inappropriate adoption of the customs, practices, ideas, etc. of one people or society by members of another and typically more dominant people or society.” Cultural appropriation is a topic that is either explicit or implicit in our classrooms and one that must be acknowledged and addressed in our artmaking practices. Interestingly enough, Spongebob Squarepants has been accused of cultural appropriation.

Cultural appropriation in the classroom is tricky.

To ignore teaching a variety of cultures in art is to deny the very essence in which art is created. However, when we teach a project specifically based on a specific culture, we are teaching our students that it’s okay to appropriate that culture, but we also miss an opportunity to connect students with applying a specific technique to express their interests.

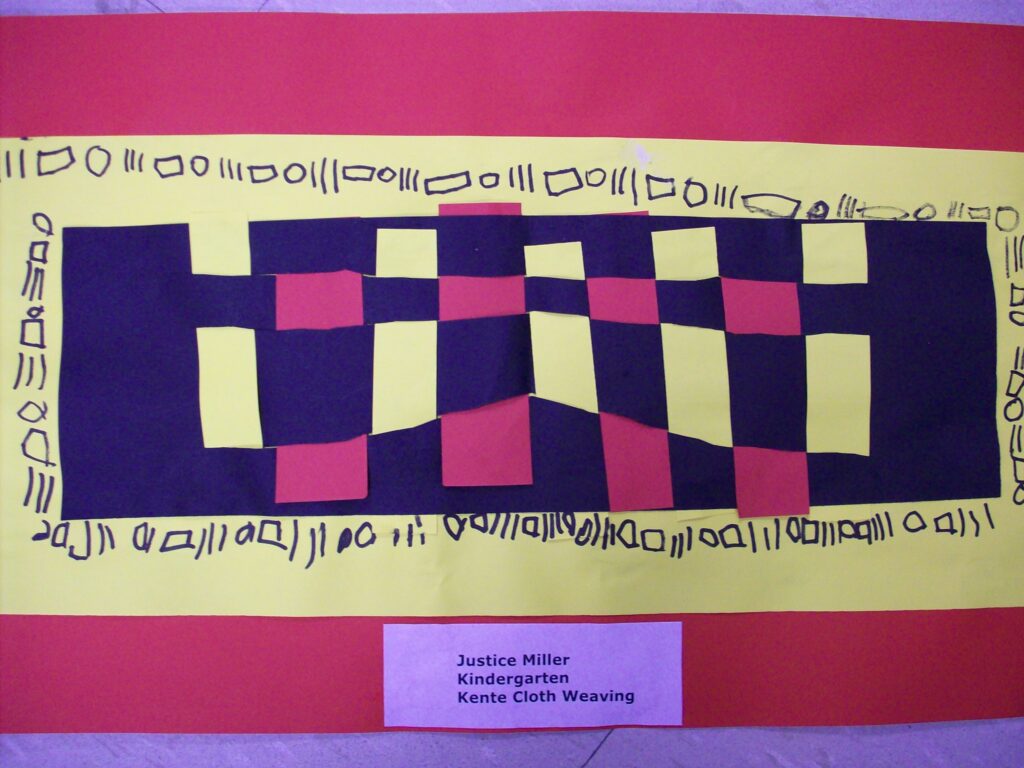

For example, consider teaching weaving to elementary students. Teachers will often teach paper weaving and have students create a colorful and geometric weaving project reflecting kente cloth. As a teacher, you are probably teaching about the rich history of kente cloth to your students. Students practice weaving and create beautiful paper weavings.

You might be thinking, what’s wrong with this? As a teacher, we are exposing our students to cultures through artmaking. However, it is important to acknowledge the responsibility we bear to consider the ways we teach cultural and artistic connections.

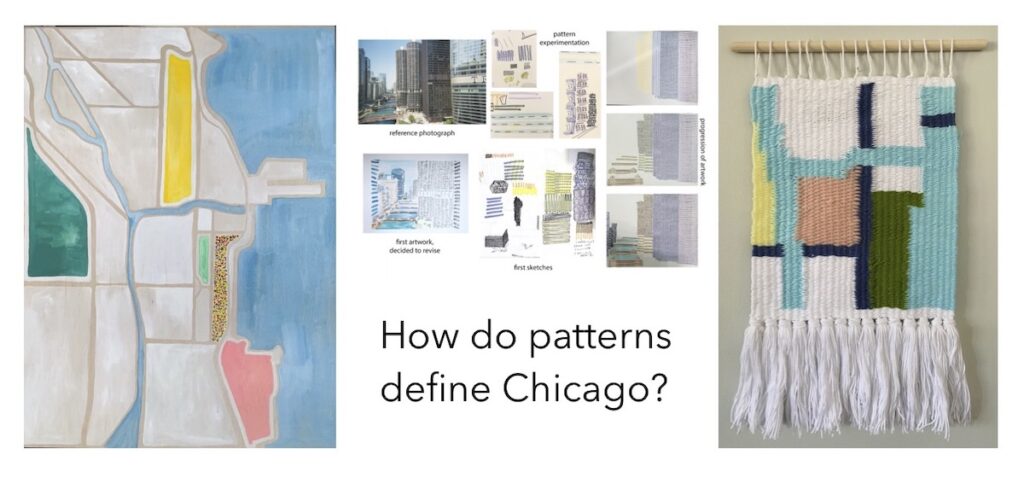

In our kente cloth weaving project, we are missing an opportunity to teach weaving in a way that explores important qualities and identities cultures form through their textiles. Instead of replicating specific colors and patterns to teach weaving techniques, we can ask our students to connect with ways artists make intentional choices in their fibers to tell a meaningful story.

Instead of using kente cloth to teach weaving, teach weaving to introduce kente cloth.

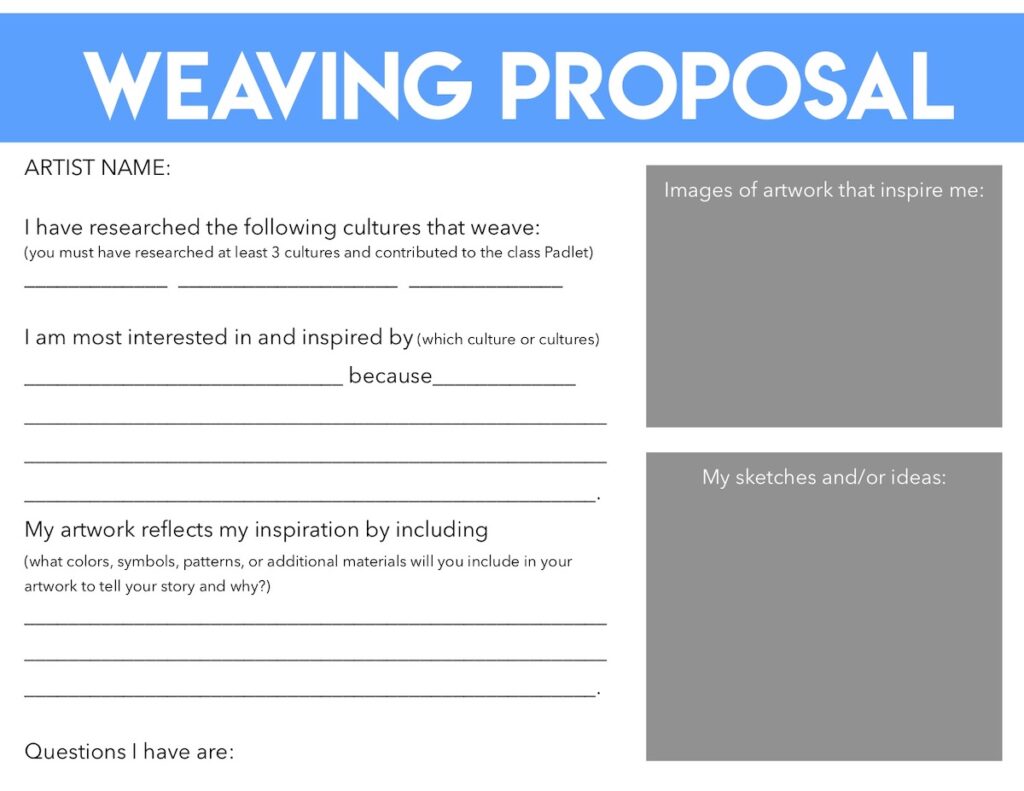

- Teach students how to weave with paper or other materials.

- Let them practice techniques, explore various materials, and identify colors and patterns that interest them.

- Introduce your students to a variety of cultures that use textiles in meaningful ways.

- Ask students to identify what they notice about each culture’s textiles and the significance behind each.

- Discuss connections and the significance of function, colors, and design demonstrated in each culture.

- Guide students to draw their own personal connections to begin creating a personal textile.

- Talk to students about cultural appropriation. This is a great opportunity to discuss the differences between replicating and being inspired by others.

- Talk to students about intentional decision making and how artists learn from history and rich cultural knowledge to inform their artmaking decisions.

Here are a few easy guidelines to remember:

What is NOT appropriate:

- Replicating other cultural artwork.

- Using cultural artwork as a costume.

- Using cultural language in a vague or generic context.

Student choice will lead to deeper connections.

Choice allows opportunities for students to authentically connect with cultural context. Flipping your teaching practice gives students ownership over an artwork through research and interpretation. When students have to justify their artmaking choices, they will make deeper connections with the cultural context they are researching.

When we teach students how to research, ask students questions about their choices, and point out connections we see between cultural references, students will gain a deeper appreciation of both art and art used in cultural contexts. Be careful not to use a student’s choice to avoid educating yourself on a particular culture. Take this opportunity to do some of your own research to help guide and support your students’ decision making.

For example, when we teach a project based on a specific cultural context, students will take what we say and create from that lesson. If we teach a pinch pot lesson around sugar skulls and Dia de Los Muertos, students create artwork based on the saturated colors and decorative patterns they see. They only connect as deep as our instruction.

Back to our pinch pot example, we can teach students how to create a pinch pot and then ask them to research their own interests or cultures. You might even provide a list of cultural references to get students thinking about all the different paths to pursue. Students take ownership of their choices and learn to defend their choices by sharing their knowledge of the context they research. When we expose students to a range of cultures but then require them to consider their own interests, students bridge from copying to creating unique and personal artwork through inspiration.

Curiosity, research, and reflection guide our teaching.

Asking questions and thinking deeply are powerful tools in the art room. As teachers, we don’t know all the answers. Often, teachers can feel uncomfortable teaching about a culture they may not fully understand themselves. We are afraid to make mistakes, teach something incorrectly, or gloss over important aspects of an unfamiliar culture.

A Project to Help Teach Your Students About Appropriation

A great way to start a conversation is to infuse questions into your daily practice to guide students through their artmaking choices. For example, while teaching jewelry/metals, I have become keenly aware of how functional art is at high risk for cultural appropriation. When researching, students gravitate toward designs, symbols, or forms they like; they don’t always know the contexts those images embody.

How to Avoid Cultural Appropriation in Your Lessons

Engage your students through a scaffolded research approach. You might start by sharing a few specifically chosen resources with your students, such as books or artists’ websites. Involve your students in expanding your resources. Creating a Padlet is a great way to have a bank of resources organized by cultures, techniques, and media. Not only are your students helping build resources to share time and time again, but they are visually connecting commonalities between techniques, media, and cultures.

How to Deal with the Idea of Appropriation in the Art Room

Through curiosity and reflection, we can push students beyond the surface of aesthetics. Instead of telling students what to do or not to do, we can lead the conversation to ask students why they are drawn to specific images, colors, and designs. We can teach students how to connect with specific cultures and the rich contexts these items carry.

Here are some questions to ask your students while they are creating:

- Why is that color important to you?

- How do you connect with that particular symbol?

- What function does your work have?

- How are your choices influenced by cultural significance?

- How do your choices represent the meaning you intend?

- If this symbol is important to a particular culture, how can you choose a symbol that represents you?

As art teachers, it is our responsibility and obligation to constantly reflect on what and how we teach. Teaching cultures in the context of art is a foundational piece in art education. When we fear teaching something incorrectly, we unintentionally silence our world’s rich cultural history that we borrow from on a daily basis. Helping our students gain awareness of these diverse connections through their own artwork develops a deep appreciation for all cultures and their world. In doing so, we demystify the differences and engage in teaching through an anti-racist lens.

A special thank you to Jeff Sturgeon and Marie Weston, who helped spark this conversation via our book club and continually asked the hard questions to reflect on our own teaching practices. Another special thank you to Dr. Wynita Harmon for helping steer and hone the conversation to apply to all levels of our art teaching.

In what ways do you unintentionally appropriate cultures through your teaching?

What questions can you ask students to help guide them in learning about various cultures through their artmaking practice?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.