Amid tumultuous times, or even during a personal struggle, the art classroom is our students’ go-to safe space. Whether you are engaging in personal conversations or providing relevant topics to discuss, student artwork can be controversial and emotional. Some topics are essential to include in the classroom, while others may be too triggering to tackle. So, how do you support students as they create artwork that is personal to them without pushing for a particular cause? What happens when students don’t want to discuss topics that may provoke inner trauma? What if students simply want to enjoy your class as an escape from their daily struggles?

The choice art classroom is set up for just this purpose: to provide students the choice to create through their own artistic voice.

Step 1: Create A Safe Space

We all know how important it is to create a sense of community in our classrooms, starting from day one. Creating connections both teacher to student, as well as student to student, takes time and consistent practice. Our students will not feel comfortable being vulnerable if they don’t feel safe, and that goes for the entire classroom.

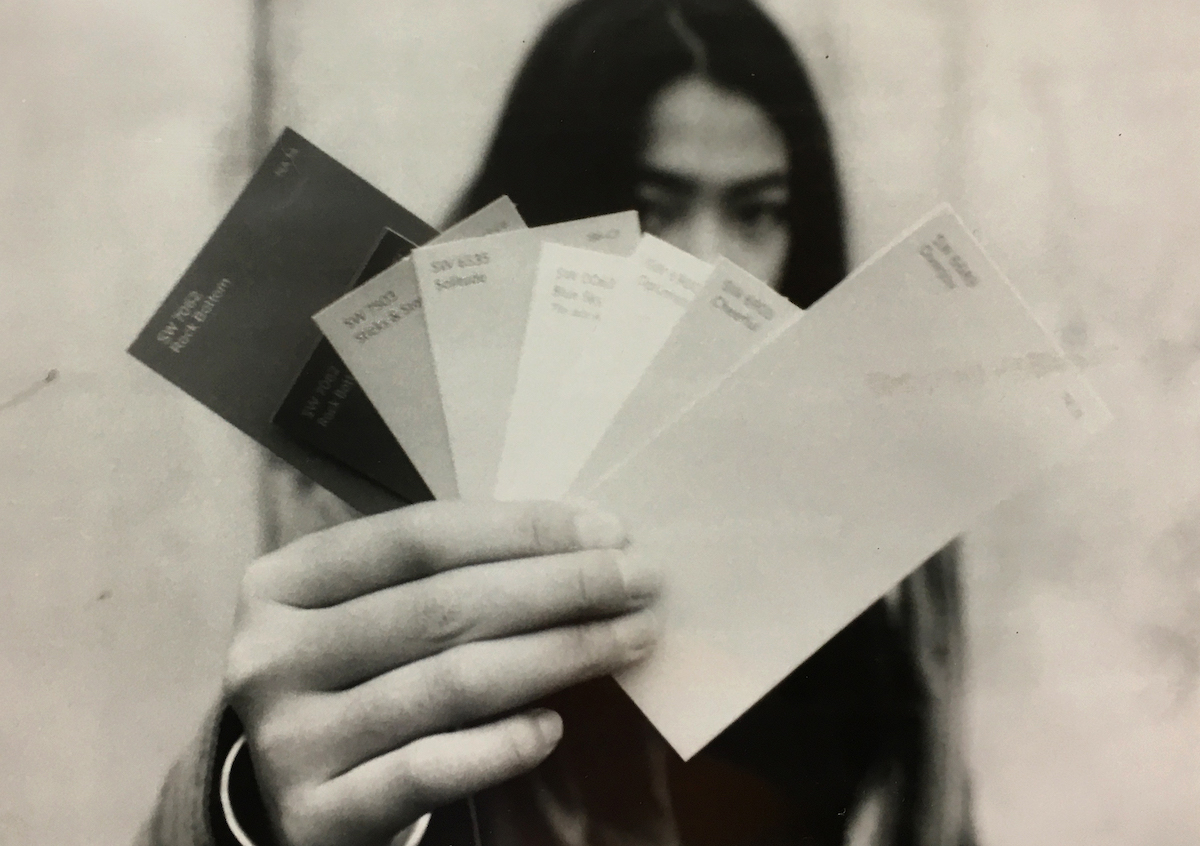

One way to foster a strong sense of belonging is through a sketchbook. Whether you purchase these for the class or students assemble their own, creating ownership over this book is the first step. First, redefine the term “sketchbook.” Redefining your sketchbook as a visual journal or artist book will transform the purpose of this book into a personal space. This book is not simply a place to diagram or plan for artwork with a few sketches and notes. Instead, this book is for them to create whatever they want inside! The goal is to write, think, paint, draw, collect. The idea of planning for an artwork transforms from a worksheet of three to six sketches into a true discovery process that is personal and sacred.

Within the classroom, setting the tone for everyone to respect all artistic voices, including opposing opinions, can really make or break your sense of community. Opinions that include hate, however, cannot be tolerated. While this seems obvious, it is also a very tricky line to tow. Your conversations about what is appropriate can lead to feelings of shame, which leads to defensive and defiant attitudes. Make sure to turn those conversations into teachable moments instead of pointing fingers of blame. Talk with your administration about their backing in situations that could be interpreted as controversial or sensitive. If you don’t feel supported, it’s hard to provide that support to your students without fear of losing your job or losing the respect of your students.

Step 2: Scaffold Choice

Once your classroom community has developed, it’s time to teach students to move into those more conceptual ideas. Often, teachers think, “If I give my students a choice of what they want to create, their technical craft will flop.” This is just simply not true. What is true, however, is that students often struggle coming up with ideas for artwork when they haven’t developed those skills yet. Conceptual ideation needs to be taught with supports in place, just like technical skill development. Teaching your students how to not only come up with their own ideas but also address personal concerns will take just as much practice as learning how to master watercolors.

Step 3: Provide Opportunity

When you’re ready to have students create wholly on their own, one way to provide structure is to limit the number of topics to explore. Asking students to create an artwork around, let’s say, “world peace” is like asking an art teacher to go ahead and teach science tomorrow. Sure, you know how to teach and, sure, you know something about science (some more than others). But to create personal investment, students need to be exposed to the ways different artists tackle these large ideas. Taking time to investigate artists’ work helps students break down their understanding of how they, themselves, might attempt that same topic. Then, students need to connect with these ideas on a personal and specific level. The “world peace” topic is just too vague. Where should I start? What if I don’t want to create an artwork about world peace?

Instead, provide one overarching prompt with many different artists who grapple with those same issues. Students can see how artists might hone in on one inquiry within that larger topic and explore materials and research to create more developed works.

Another approach is to provide three different prompts from which students can choose to inspire their own artwork. All students must partake in learning about each prompt and discovering artists who tackle these prompts. The three choices usually cover a range of interests.

One prompt focuses on aesthetics and design, which often has a deeper context but demonstrates more of a concrete understanding of design qualities. For example, “Artists Repeat” might be a prompt introducing Yayoi Kusama and Yinka Shonibare. The second prompt is usually more conceptual or abstract; for example, “Artists Find Inspiration in Words.” This prompt pushes students to interpret lyrics, poetry, or creative writing into visual artwork.

The last prompt connects students with global or community concerns. For example, “Artists Take a Stand” asks students to consider their own personal connections to the world around them through a social justice lens. We look at artists such as Lewis Hine and Wendy Red Star to see how artwork responds to human rights and inequity to create change.

If a student has no interest in any of your provided prompts, more than likely, something you provided (prompt or resource) has sparked something else they are personally interested in exploring. Providing opportunities for students to pitch a proposal helps clarify their ideas while also respecting their own authentic learning process.

Step 4: Encourage Connection

Why invest three weeks in an artwork you have little understanding of or even care about? When teachers force a specific social justice prompt, students often create inauthentic and cliche artwork. You may care about climate control, but how are you personally invested? What research have you done to support specifics within your work? The best way to encourage student ownership and personal investment in the process of creating their artwork is to ask them what they are interested in creating and why. Sparking lines of questioning helps students decide how they will connect to create meaningful artwork.

Remember:

- Students carry invisible trauma. Art teachers are not trained therapists. Be careful when prompting sensitive content. Know your school resources and find out how students can receive support when needed.

- Teachers are mandatory reporters. Symbolism in artwork or personal thoughts written in a journal are subject to liability. As a mandatory reporter, it’s essential for students to know that, while they should feel comfortable expressing their thoughts and feelings through their artwork, it is your responsibility to contact the appropriate channels if there are concerns for their health or safety.

- Instill balance in your curriculum. Not all students want to create artwork around social justice issues. That doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be exposed to them. If you feel like you must incorporate a project that focuses on one particular issue, consider making it into a collaborative or creating on a smaller scale. Students should be expected to try out different ways to express themselves through their artwork, and it is our responsibility to provoke thought by asking students to consider difficult questions. However, creating on the theme of social justice should not be the sole driver in your classroom. Mindfulness through observation, for example, is also important. Again, crafting your teaching philosophy is critical.

While this only scratches the surface of providing choice in your classroom to promote student voice, don’t forget it takes many pieces involved for students to feel safe before addressing vulnerable topics. When teachers wonder why their students’ artwork looks cliche or student interest wanes, take a look at how you’ve set up a safe and supportive classroom to support choice.

What are your favorite ways to create a community in your classroom?

How do you support student voice in your classroom?

In what ways do you support students when discussing controversial topics?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.