Do you have a love-hate relationship with grading? On one hand, assigning grades with letters and numbers is something all students understand. But, while this standardized system appears clean-cut, does a percentage really depict learning? What does a letter really mean, anyway?

Grading systems are continually being revamped, especially as Standards-Based Grading continues to trend around the nation. What is the difference between assessment and grading? How can we authentically assess our students’ process and product without being punitive?

Here are some key points to consider when reflecting on your grading practices.

1. Grades and assessments are not the same.

How many times have you used your amazing point rubric only to find the grade doesn’t match the students’ work? You think, “Malachi just earned a ‘C’ according to that rubric, but he is making some really incredible and imaginative artwork. Liza was awarded an ‘A’ using that same rubric, but she was simply following the instructions; the work is overall subpar.” You recalculate your points and wonder, “How can this be?”

The first question you need to ask yourself is, “What criteria should I actually be assessing?” It all boils down to what you value when teaching the lesson. If you value imaginative thinking, emphasize this idea when teaching your lesson and reflect this focus in your assessment. Make sure your criteria points align with the overarching standards you’re putting into practice. For example, if you teach a lesson where risk-taking is the focus, then the percentage of points awarded in your assessment must be worth more than other concepts. You can’t be too upset with poor craftsmanship if that wasn’t the point of the assignment. Neither should your students be docked heavily for it.

2. Redefine what you value.

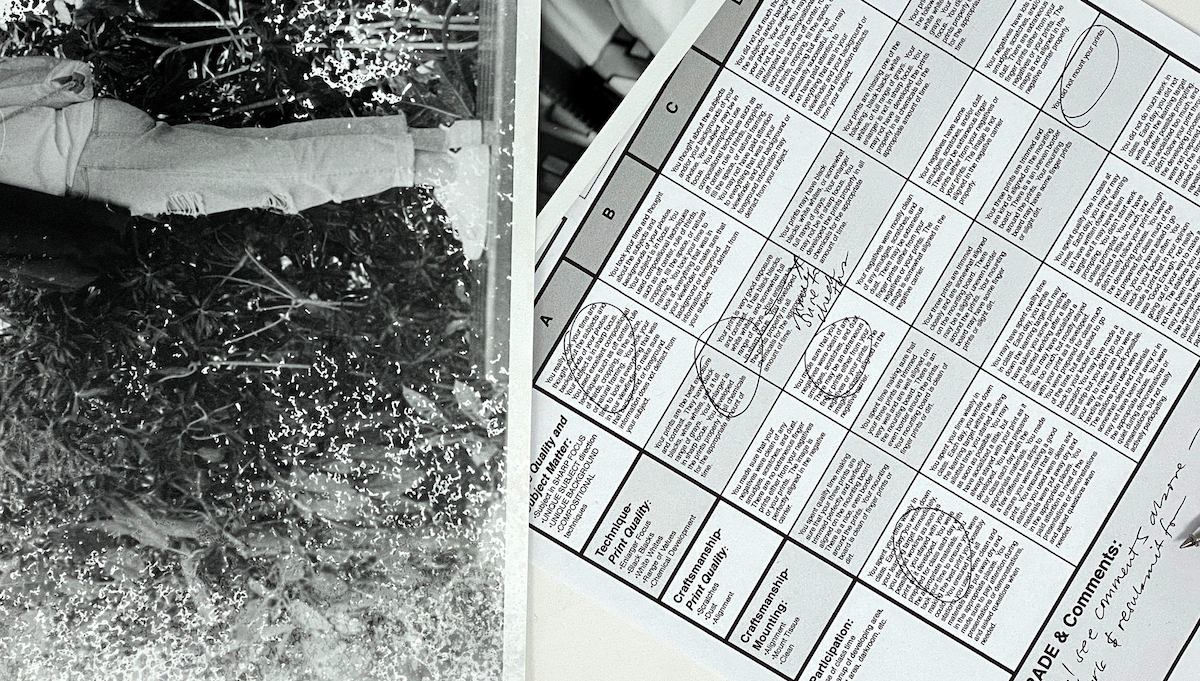

The second question you need to ask is, “How should I be assessing?” Checklists, rubrics, point sheets, and reflections are all valid forms of assessment, depending on what it is you are assessing.

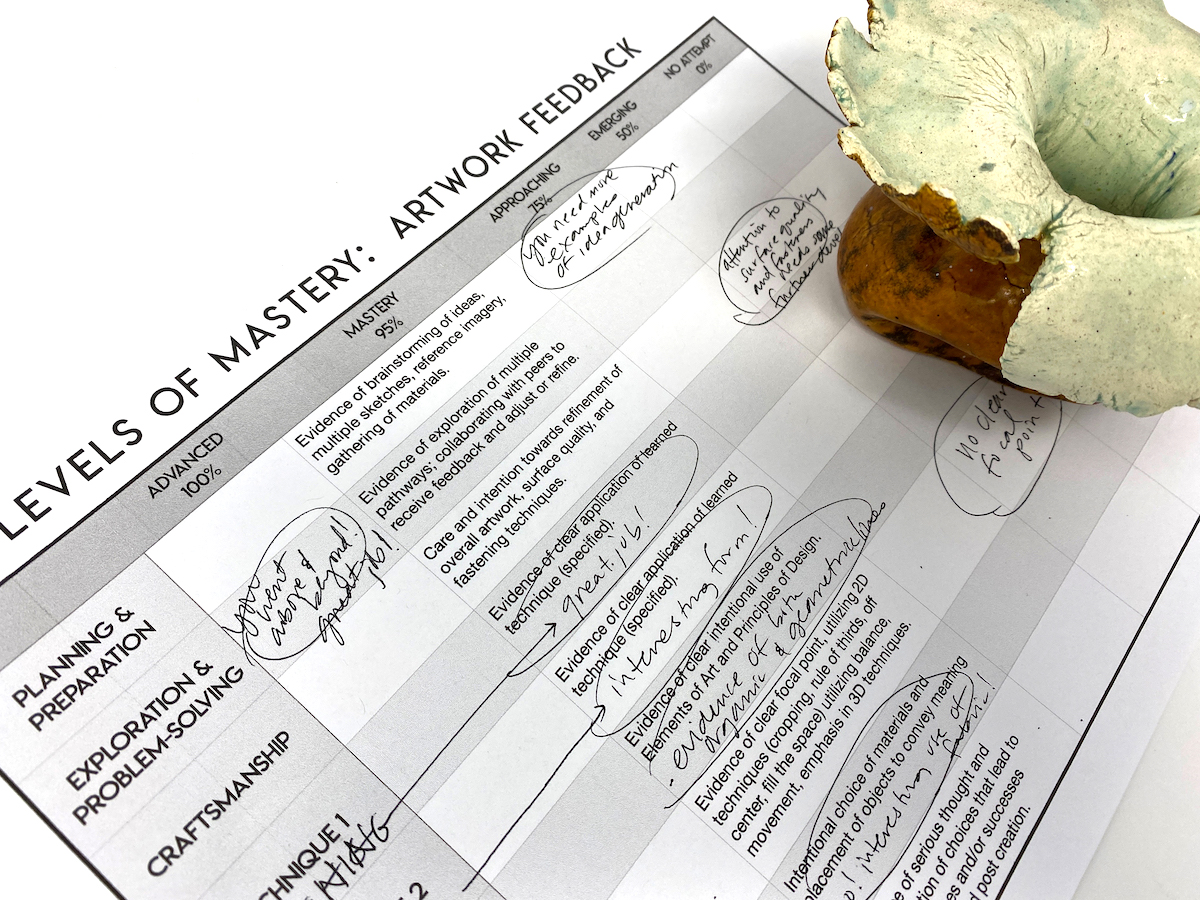

Rubrics are important assessment tools, especially for end-of-unit artworks and final exam portfolios. They are valuable when you are looking for specific techniques and concepts taught throughout a particular work. A thorough rubric can help make grading a snap. Descriptors in each category demonstrate what you are looking for in quality work and easily identify where a student needs improvement. Sometimes putting number values to your rubric, however, can limit your holistic view.

Levels of proficiency are a great way to help students gauge where they are in their learning process. When building technical competence, for example, we want to make sure students understand what different levels of quality look like. When giving a grade for technical skills, break it down into different strategies or techniques to help a student identify where they might be struggling. Instead of giving a “C” for drawing a realistic still-life, empower that student with targeted areas for improvement. Define key techniques such as shading, line weight, and scale. A student can then determine exactly where they went wrong and with which specific skill they need more practice.

Align assessments to essential questions and standards.

Looking at standards or essential questions can also help redefine the importance of your students’ creative process. If they take only one class with you, what do you hope your students have learned? Exploration, risk-taking, and reflection are key aspects to creating. How can you encourage creative thinking without squashing it through assessment? Taking risks is a vulnerable thing. If our assessments do not reflect this value, the artwork is penalized, and students will stop taking risks for fear of failure or punitive marks. For example, if you value risk-taking and exploration of new media, then you cannot give a consequence when that risk doesn’t pay off in the end product. However, you can ensure that the student has learned from taking those risks through reflection and revision opportunities.

Student voice through reflection demonstrates learning.

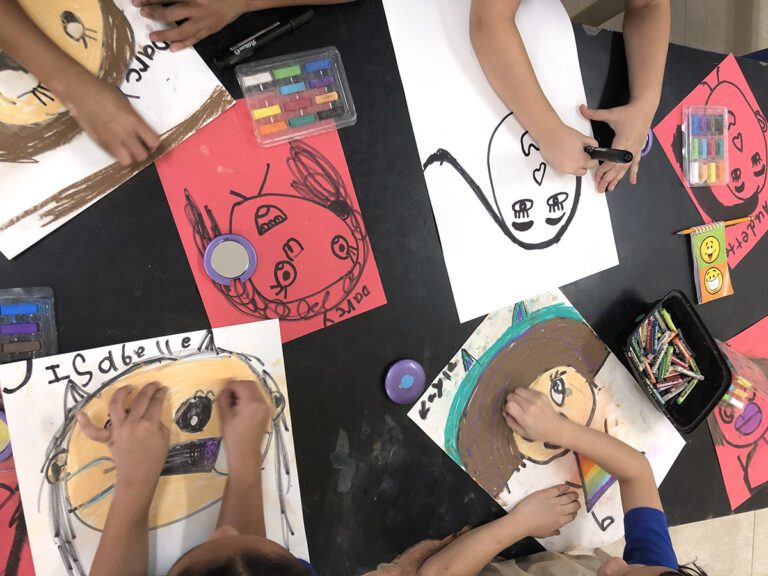

Self-assessment, reflection, and metacognition are essential aspects of the learning process. When students are able to articulate ways in which they have learned, struggled, and achieved success, we are empowering them to authentically engage with their learning. Instead of focusing on the end-product, implementing daily reflection on their individual goals will ultimately drive their product over time. Emphasizing the process over the end result focuses student thinking on day-to-day learning and less on achieving a specific result. Developing students’ creative process will ultimately drive their end product.

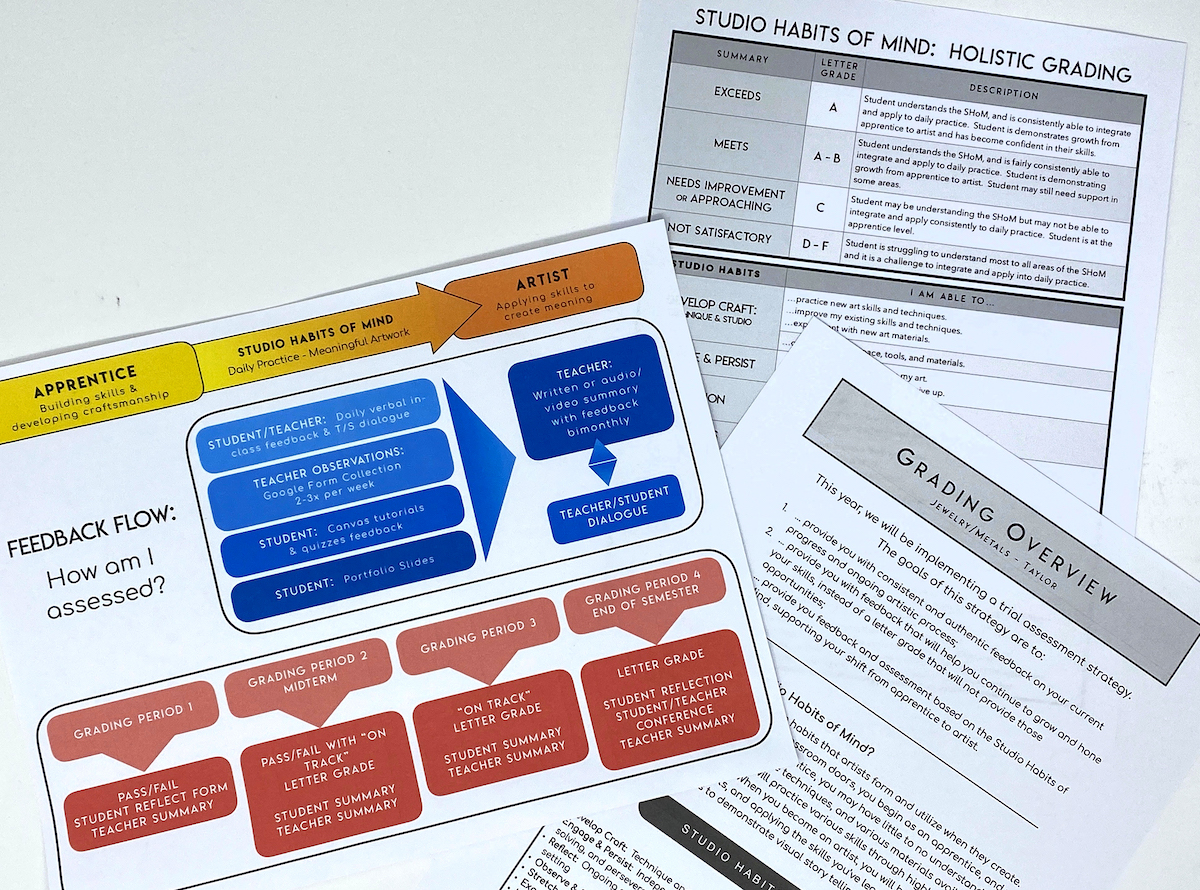

One way to do this is through The Studio Habits of Mind. When utilizing these as your standards, you are reinforcing overarching daily habits artists go through to create. We know technical development is crucial to visually convey our ideas, but we also have to help our students develop ideas in the first place. You can use these as assessment standards when looking at how your students are learning and growing as artists holistically.

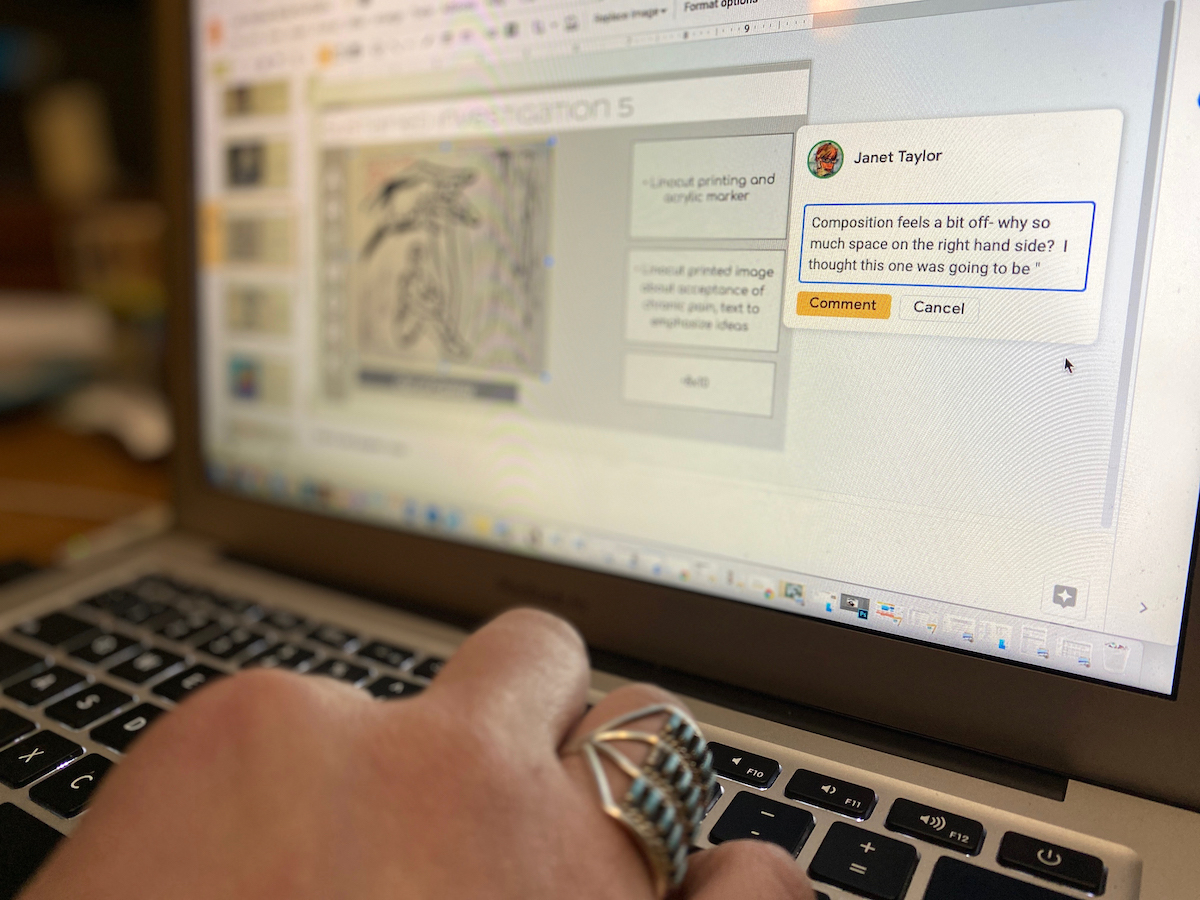

3. Focus on the feedback.

We all know feedback is essential for students to learn and grow. It’s important to ask yourself, “How are my grades providing valuable feedback?” Grading simply teaches students how to check the box to get that “A.” Feedback provides students the opportunity to improve through refinement as well as to value their process and achievements. There are different levels of feedback: daily nudges in the right direction, peer critique as they develop their critical eye, written notes on your assessments, or even one-on-one conferences. All levels of feedback are valuable to the growth of a student.

Ensure your feedback is what drives your students’ learning and not the grab for the grade. Hold students accountable for that feedback. Expect your students to not only use feedback to improve their work but also discuss ways in which feedback pushed their ideas further or helped them hone their technical skills along the way.

4. They might not do it either way.

Taking grades out of assessment has a lot of benefits. But, let’s be honest: the same kids who didn’t write reflections when they were receiving a grade are often the same kids who won’t do it without a letter grade, either. Taking away the letter grade for particular aspects of learning does take the anxiety out of the process. However, it won’t miraculously change the hardest to reach students into fully engaged learners. Students who are disenfranchised by the educational structure, who are used to being penalized no matter how hard they try, and who are not necessarily recognized for their own unique intelligences are going to take time to trust these new expectations.

Taking risks and allowing yourself to fail is a very vulnerable endeavor. If a student isn’t submitting reflections for their work or filling out their daily goal sheets, it doesn’t mean they aren’t learning. Instead of losing points left and right for not completing these tasks, shift the focus to growth. This allows students opportunities for success in a variety of ways. That’s not to say students shouldn’t reflect just because they don’t want to. Instead, focus on what they are creating and developing in your classroom, and look for other ways to demonstrate reflection. By doing this, you are modeling that you value what your students have to offer regardless of their weaknesses.

5. They still get a grade because they have to.

Most educational systems still expect you to provide a letter grade that sums up student achievement in your class. How can we get around stamping a letter on their learning? One way is to zoom out and look at students’ growth over time.

Did your students take risks, explore media, develop techniques, persevere through obstacles? Did they apply this knowledge to create personal and meaningful artwork and articulate how they did all of this? Compare the very first and last artworks your students created in your class. Can you and your students identify ways in which they have grown as artists?

Take another look at the standards. If students missed big sections of learning, how is this reflected in their overall grade? Consider what you value. Does what you value help develop the student who may never take another art class, as well as the student moving to advanced levels? Do different course levels value different expectations? It’s essential to consider how your grading practice, and the letter grade the student ultimately earns, is aligned to all of these factors.

As educators working in a school system, we are confined to the grading and assessment policies of our district administration, state, and nation. As art educators, we are often fortunate enough to have some flexibility and autonomy as to how we work those policies to enhance student learning in our classrooms and departments. Regardless of how you assess your students’ work, be reflective and authentic to what is best for your students in your community. Don’t forget to be creative in how you view authentic assessment to best enhance student learning in your classroom.

What criteria do you use to assess your students?

How do you grade your students? Do you focus on process, product, or both?

How can you work with your administration to develop authentic assessment?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.