Our art rooms are magical places where we see a wide range of neurodiverse students. This is probably one of the most exciting parts of being an art teacher; celebrating inclusivity! When developing lessons, we need to provide opportunities for all learners to find success. Differentiation in your classroom is key. But what exactly is it, and how do we support our students without losing our curriculum’s rigor?

What is Differentiation?

In an interview with Carol Ann Tomlinson in EdWeek (2008), she states:

“I define [differentiation] as a teacher really trying to address students’ particular readiness needs, their particular interests, and their preferred ways of learning. Of course, these efforts must be rooted in sound classroom practice—it’s not just a matter of trying anything. There are key principles of differentiated instruction that we know to be best practices and that support everything we do in the classroom. But at its core, differentiated instruction means addressing ways in which students vary as learners.”

The great news is that we often already differentiate art instruction with ease. Our standards allow for flexibility to address our diverse learners and meet them where they are. Differentiation in the art room comes more naturally as we celebrate each students’ individual artistic voice and self-expression. Let’s take a look at some intentional ways we can plan for differentiation within our lessons.

Differentiating Lessons

When planning your lessons, consider your students’ visible needs and the less expected challenges students have in learning and creating. From fine motor skills, abstract thinking, and emotional readiness, providing a choice will inherently differentiate your lessons. Scaffolding with choice provides opportunities for students to learn wherever they are to achieve personal success. This is not to say you shouldn’t challenge your students to push outside their comfort zone and grow. There is a distinct difference between enabling a student and supporting their learning.

The What

Consider the content you are teaching. We often start with the end-product or goals in mind. Take a look at what you want students to create and consider your assessment. Reviewing your concepts and objectives will help focus your essential learning standards. Providing a rubric that outlines 3-4 essential standards gives students a starting point for creating. The remainder of your options are there to support learning and individual artistic voice.

For example, if students are creating a one-point perspective drawing, your essential standards may include accurately using one-point perspective, developing an image using varied line weight, and using shading to create emphasis.

One choice students have is what they are drawing using one-point perspective. Perhaps a bedroom, or the school hallway, or even down their neighborhood street. Another choice is how they creatively enhance that room, hallway, or street. The opportunities for adding imaginative qualities into their drawing are endless. Asking students to explore “who lives in the room,” or “what happens to your school hallway in an apocalypse?” still focuses on demonstrating the essential standard while also encouraging them to take risks. The content is differentiated to provide space for personal exploration.

The How

Another way to differentiate your lessons is through material choices. While it may be harder to offer many different materials at once, we can still differentiate within what we offer.

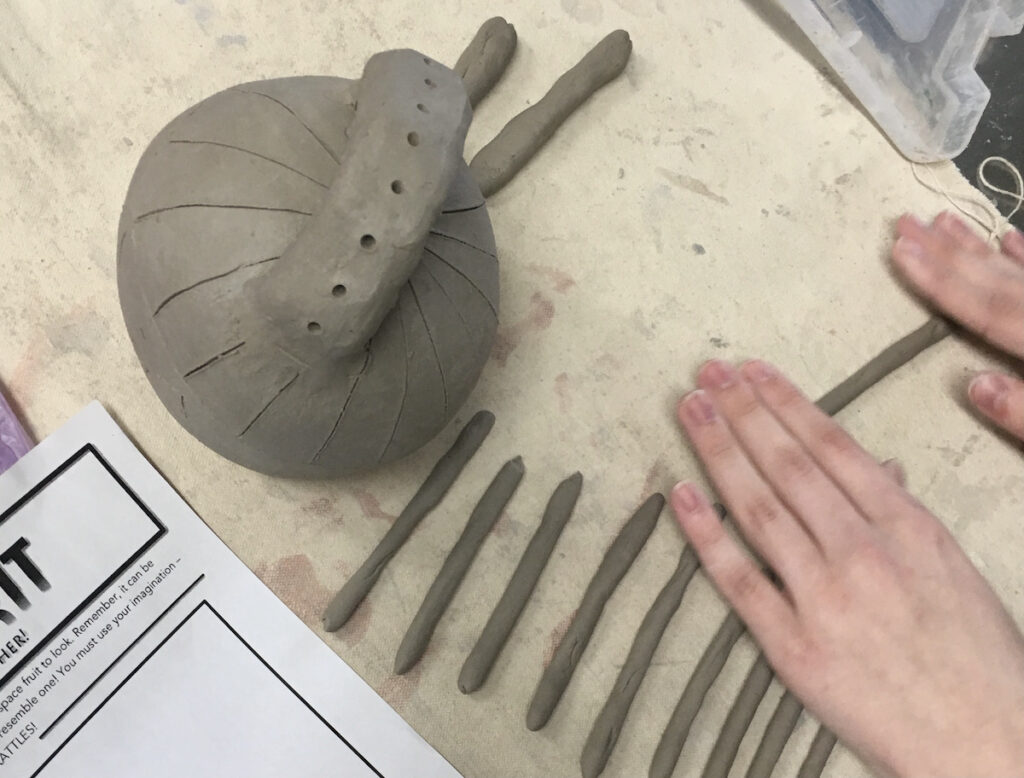

One example of differentiating materials is looking at various levels of difficulty within the media. If the focus is on color schemes in a lesson, try including colored pencils, oil pastels, and watercolor. Demonstrate each, let students explore and practice each, and then let them determine which media they want to explore further in your lesson.

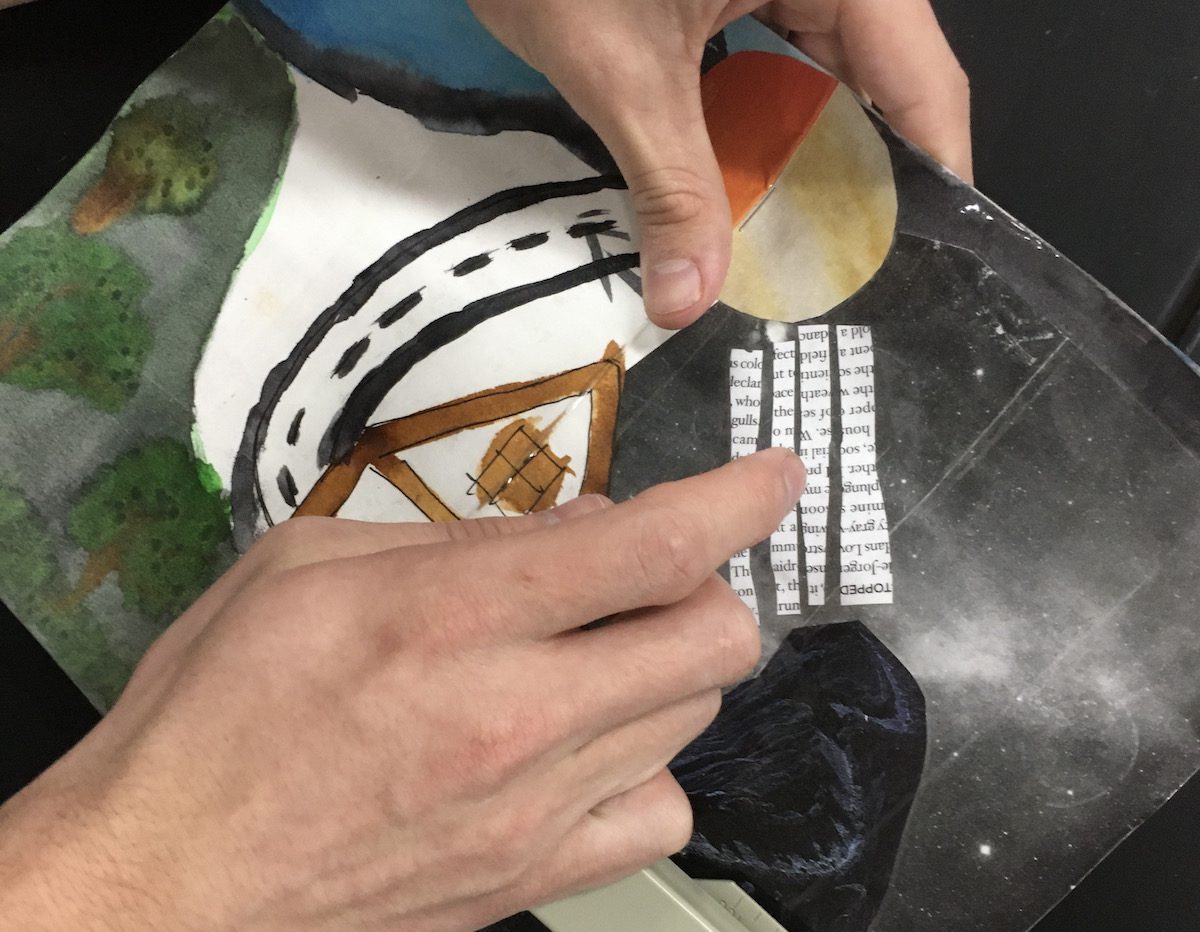

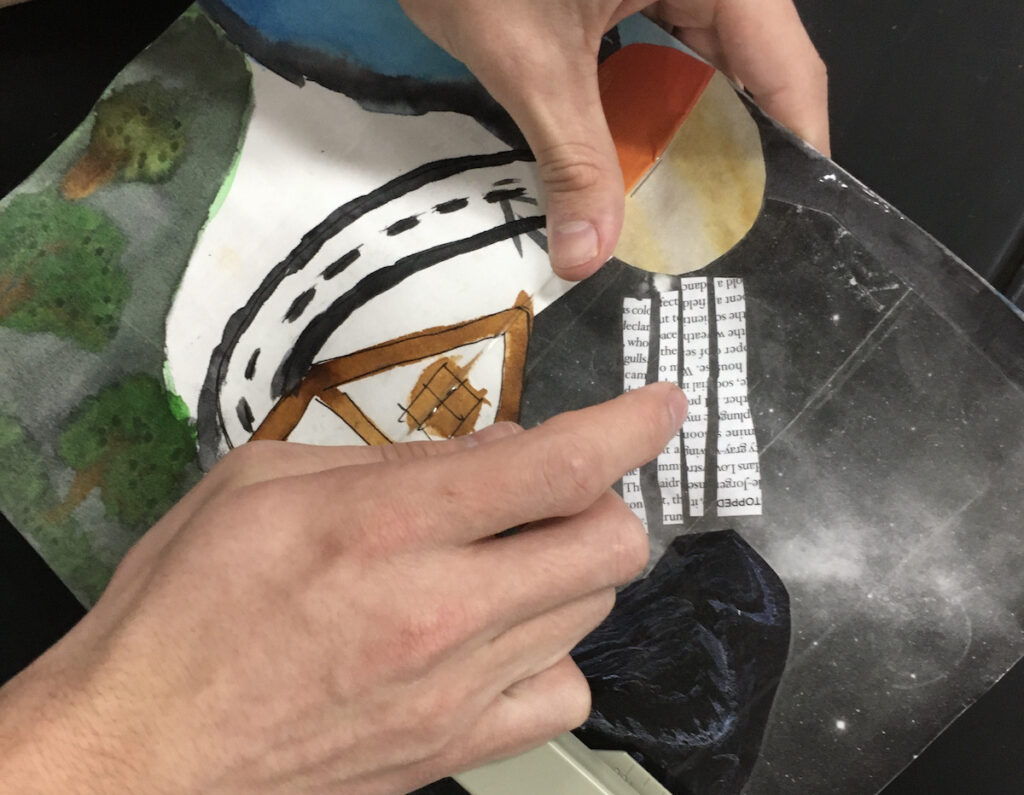

Another example of differentiation within one media includes how that media is being used. For example, when teaching a unit on collage, consider students’ varying levels of fine motor skills and sensory needs. Before creating a collage artwork, students can explore the differences between tearing paper and cutting paper. Then, ask students to cut out an image precisely with scissors, and more advanced students can try using a precision knife. Consider how students will glue paper to their artwork. Students can explore composition with imagery, where gluing skills may not be as demanding. They can also practice filling in a precise image outline by gluing torn or cut colors.

These methods are valid ways to create collage artwork, and all of these exercise fine motor skills and practice. Once students have been exposed to these techniques, you can then offer a choice of collage method to create the final artwork. Students may choose a technique they feel most confident in, but it will challenge all students to create an artwork using those fine motor skills.

The Why

Yet another way to differentiate for your students is to consider why they are creating. Students’ personal connections to their work support engagement which leads to persistence and perseverance. But not all topics are emotionally appropriate for all students.

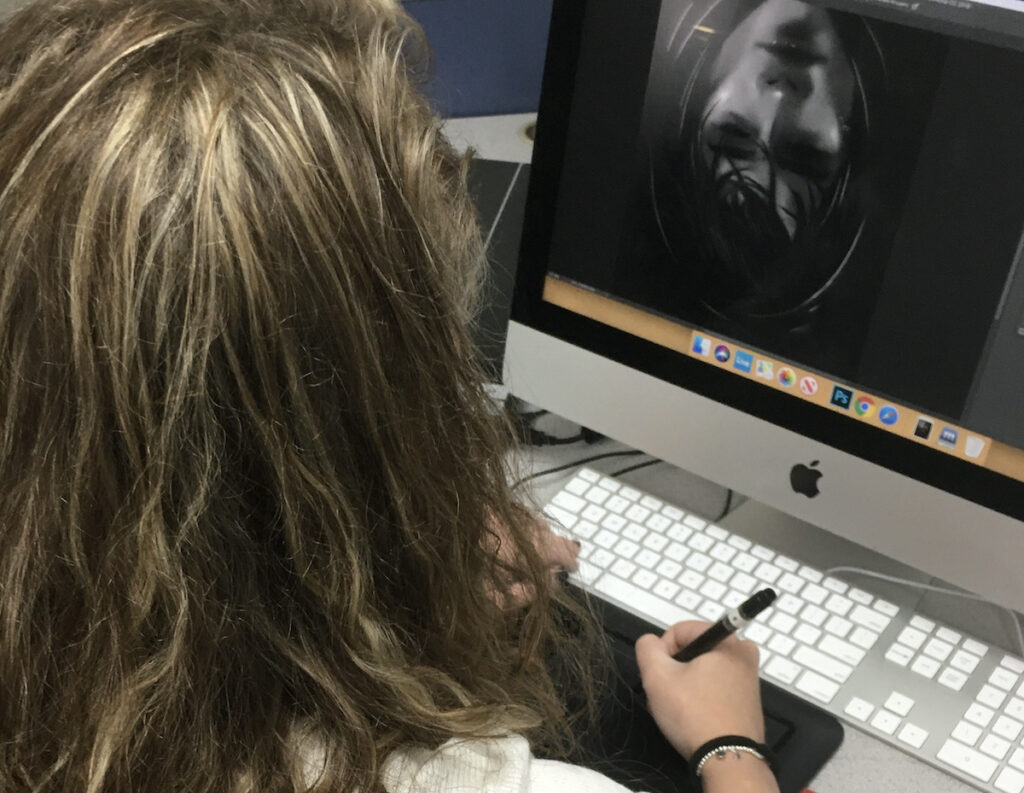

One example of how to differentiate “the why” is to focus on the skills you are assessing while providing three different ways a student could demonstrate those skills. When teaching photography, for example, you might end a unit with students producing four prints to represent a chosen topic. Your themes or topics should range in emotional approachability. Three differentiated themes could be (1) observe objects in an unexpected way, (2) create through the inspiration of song lyrics, a poem, or short story, and (3) create a social justice response to something important to you. In each of these examples, you are assessing the quality of the print, the ability to use artistic choices like composition and light, and how to tell a story visually. How the student demonstrates those skills is at a varying point of emotional access.

The Where

Where students learn is yet another example of differentiation. Students can learn in a whole-class lecture on a foundational learning level, in small groups, one-on-one, or through collaborative or independent means. When considering differentiating, however, we are looking more closely at how specific students learn best. Provide opportunities for students to create in the way that makes them most comfortable while introducing other ways to learn from each other. When providing these spaces, students may decide they would like to work together on a collaborative artwork, create an online store to sell mini artworks, or pitch a proposal for a hallway mural.

Differentiation may feel automatic in our current teaching practices. Take time to reflect on your current lessons and check for places you can add in more choice. When we consider the what, the how, the why, and the where, we ensure opportunities for success for all learning styles and needs.

In what ways are you already differentiating your lessons?

How do you provide choices to support all types of learning?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.