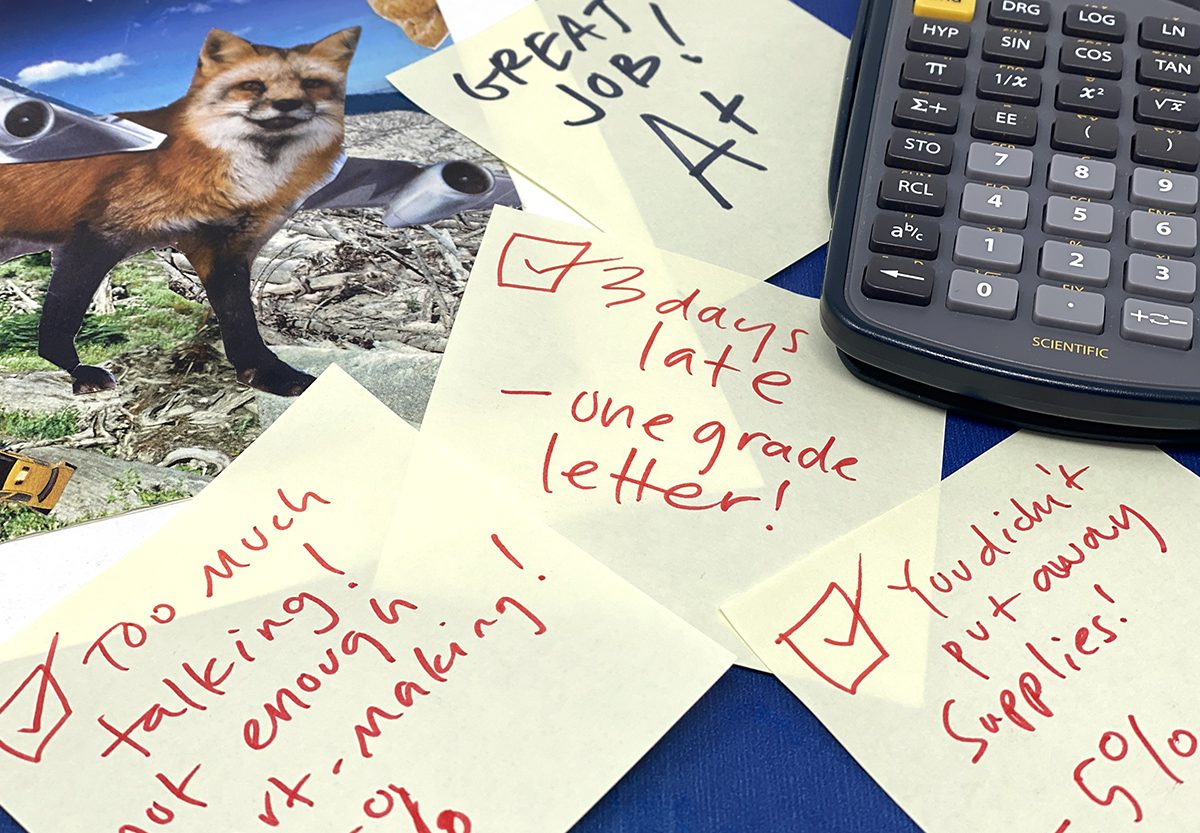

We have heard it a million times—artwork is hard to grade. It feels near impossible to put a percentage to students’ self-expression. Especially through the pandemic, grading has given many of us quite the pause. So, I will let you in on the real reason we hate to grade. Grades are neither accurate nor equitable.

Go ahead and try to argue. Believe me when I say that I have spent years working on my assessment strategies, which are still far from perfect. Every piece of this article is written from grading practices I also have once used, done, and perpetuated in my very own teaching. If you are familiar with my other AOEU content, you will know that I geek out over authentic art assessments. But when it comes to aligning your rubrics with points and letters, now we are now talking about a different beast.

Don’t get me wrong. We know you have spent hours and hours conjuring mathematical magic into the perfect point system and weighted categories. Of course, you strive to be accurate and fair. We grade because it’s the system we grew up with, and it’s the system that exists. However, that does not mean we should continue down that path.

Read on as we answer four questions that address how grades are inequitable and then explore what you can do moving forward.

1. Why are grades arbitrary?

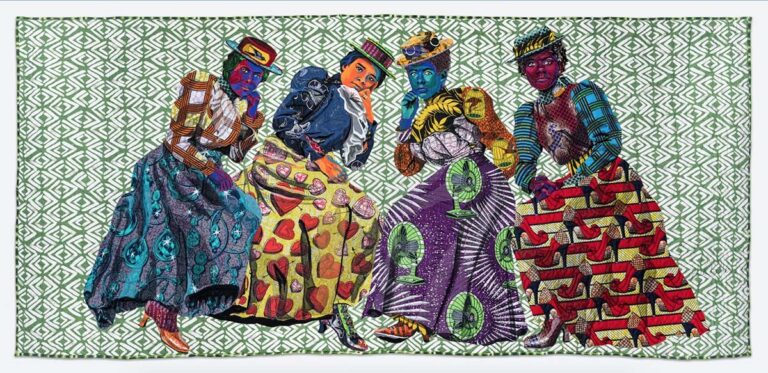

There is a reason why grading artwork can feel so icky. How do you quantify a visual art masterpiece in the first place? Let’s take a look at a common scenario.

You create a rubric with descriptive criteria, assess artwork based on the rubric, and then assign a letter grade. Two students receive an A. Most grade books, however, are set up with a 100 point system. What percentage or how many points does each A-student earn? Based on the criteria, both students should earn the same, but Student 1’s use of line isn’t quite as strong as Student 2’s.

What would you do?

- Give a 94% and 96%, respectively.

- Assign a 95% to both because the rubric says each equally earned an A.

- Student 1 gets 90% and student 2 gets 100%.

- I would do something else entirely.

What did you decide? Tricky, right? The scenarios and quizzes throughout this article should give you food for thought. Consider how you came up with those percentages. Either way, you slice it, you just placed an arbitrary number value to each artwork. Maybe it doesn’t matter since both kids will earn an A on their transcript. However, as they move through the class, those two percentage points could end up making or breaking a final letter grade.

What are some next steps to move forward?

- Make the grade a dialogue between you and the student. Students can self-assess and share their reasoning. They often grade themselves harsher than you would.

Bonus: You teach them to assess their work critically as they search for specific criteria. - Change to standards-based grading. Focus on developing as an artist as opposed to letters and percentages.

- Balance summative grades with formative points. Adding in five to ten points here and there to support formative learning will give a better picture of the whole instead of risking it all on larger assignments.

2. What makes grades inaccurate?

Let’s look at our next grading conundrum. In this example, a student creates an amazing artwork. Truly, it is spectacular! This work is imaginative, detailed, and it is obvious the student took a lot of time. Of course, they have just earned an A! Then, you look at the rubric you created. According to your rubric, the student has earned a C. How can this be?

What would you do?

- Give the student the grade you think they deserve regardless of what the rubric says.

- Stick to your rubric no matter what the value ends up being.

- Rewrite the rubric to more accurately reflect what grades you think the students should be receiving.

- I would do something else entirely.

I know we have all had this happen at one time or another. How did you answer the quiz? In this scenario, the heart of the issue is an inaccurate assessment. Your rubric didn’t assess what you had expected.

For example, maybe your rubric is assessing line, movement, and compositional techniques. Reflecting back, you didn’t focus much or enough on composition. You did, however, spend a lot of time focusing on visual storytelling and choosing an interesting subject matter. If your rubric isn’t accounting for this shift in what YOU did as the teacher, you will end up assessing the wrong criteria.

What are some next steps to move forward?

- Look for evidence of thinking. Since we aren’t inside our students’ minds, we need insight into what was missed. Through reflections and artist statements, you better understand what your students were trying to do.

- Reevaluate what it is you are assessing. Did you teach the skill properly? Did your lesson change course? If so, it is time to fix your assessment and try again.

- Rewrite your rubric with the class. When the majority of students are on the same page, they will be able to identify criteria based on goals. This is a great way to engage them in the assessment process, and it also serves as a formative check for understanding.

3. How are grades biased?

You start grading artwork, referencing your well-thought-out rubric. As you analyze each piece, you start to compare. According to the rubric, two students have earned the same grade of a B. But Kevin has worked really hard on this piece. He came into class, sat down, and used every moment of class to create. Kim, on the other hand, spent a lot of time just chit-chatting with her peers. She even distracted her peers from getting their own work done, and she never put her supplies away at the end of class.

What would you do?

- Kevin definitely earned a B+ and Kim deserves a B-.

- Both students earn the same grade for the assignment, but Kim will get an overall lower semester grade because of her negative behaviors.

- Both students earn the same grade for the assignment, but Kevin’s semester grade will get a boost due to his positive behaviors.

- I would do something else entirely.

How did you answer the quiz? Grading behavior is quite a controversial topic. (Watch the Pack, Standards-Based Grading in PRO Learning.) However, items like effort, time-on-task, and participation should not be incorporated into the assignment percentage. The artwork should be assessed based solely on what the student demonstrates. Even if your state standards address behavior, you don’t need to grade them in order to give feedback. Teaching students how to advocate and communicate their needs in a healthy and productive way will go much farther than taking points away.

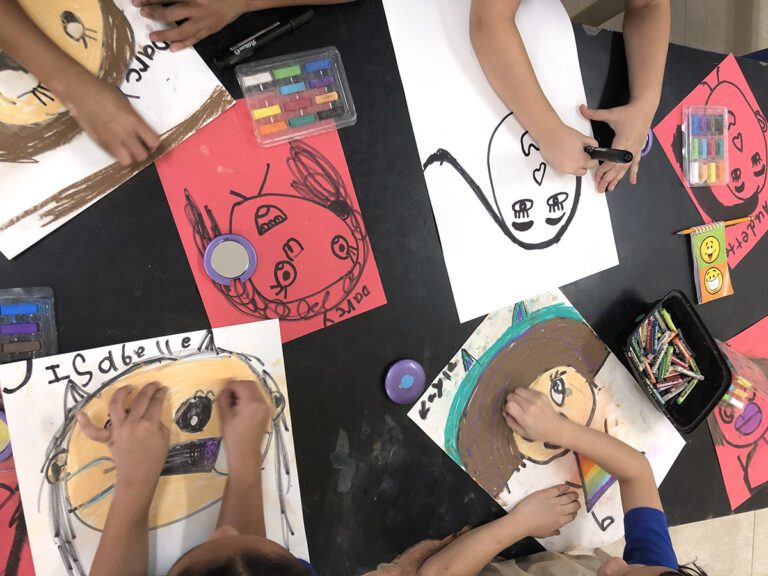

Remember, students want to behave and succeed. When they can do well, they will do well! Focus on artistic behaviors such as the Studio Habits of Mind. These behaviors support the artwork and artmaking process. We don’t need to grade this in order to see them evident in the artwork and process images.

What are some next steps to move forward?

- Give students the benefit of the doubt. The goal of grading shouldn’t be a “gotcha’” moment. Maybe you caught the student in a bad moment of their day. Address it immediately and let it go.

- Reflect on what might be falling short in your own classroom management. Use your findings to determine what interventions to implement to support struggling students.

- Seek support from a colleague, instructional coach, or student services team. Discuss concerns with parents and caregivers and look for ways to solve the issues collaboratively.

- Reevaluate what you grade. Consider how your grading practices reflect what students can do rather than your own values.

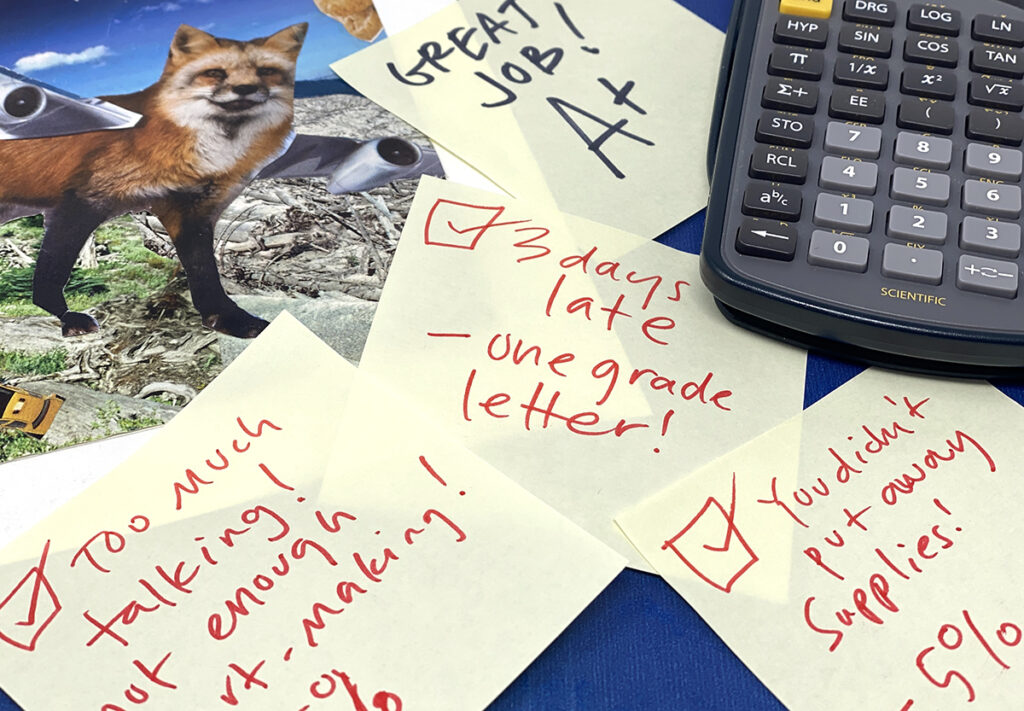

4. When are grades punitive?

Another controversial topic is the great “late work” debate. Let’s see what this looks like when a student turns in an assignment late. Perhaps your school has a policy that states, “Late work cannot receive anything higher than a C, and if the work is later than one week, it may not receive higher than a 50%.”

Brian has been really busy with soccer this semester. He forgot to work on his artwork outside of class. He whips something up and turns in an artwork on time. If he had a few more days, he would have been able to dedicate more time, and he knows his work would have improved. He isn’t thrilled with what he submitted, but it is “on time.” According to the rubric, his artwork earns a C.

Sara has been diligently working on her artwork each night up to the deadline. The day the work is due, she forgets it at home. She has now missed the deadline. She submits the work the next day. According to the rubric, she has earned an A. According to the late work policy, she can receive no higher than a C.

Caleb has been working a job each night and focuses first on his core subjects when he gets home. He completely forgot about his artwork. He turns in his artwork a week late, and it is barely finished. According to the rubric, he has received a D. Because the work was so late, points will be deducted.

What would you do?

- Brian receives a C, Sara receives a C, and Caleb receives a 50%.

- Brian receives a C, and Sara’s late work has been excused and receives an A. You feel bad for Caleb’s work situation and know he will probably fail the class anyway, so you give him a D per the rubric.

- Brian receives a C, Sara receives a C, and Caleb receives a 40% based on the rubric and the late work policy.

- I would do something else entirely.

When considering what to do when a student turns in late work, we often deduct points. Teachers argue that students need accountability to prepare them for the “real world.” According to Reeves in The Case Against the Zero, “The most common answer is to punish these students. Evidence to the contrary notwithstanding, there is an almost fanatical belief that punishment through grades will motivate students.”

Motivation by punishment does not support best learning practices. A student who is consistently late may have bigger issues on their shoulders. Perfectionism and poor self-esteem can be significant stressors for your art students, causing fear of submission. Poor executive functioning could also lead to procrastination and the inability to manage time, especially on larger assignments such as a long-term artwork. External factors, such as home life, also play a large role in late submissions. The question is not, “How do we penalize those who are not submitting work on time?” but rather, “In what ways can we support our students to submit in a timely manner?”

Another common issue with penalizing students for late work by deducting points is “the hole.” Students who dig this grading “hole” struggle to find their way out without significant external support. Consider that a student is failing your course because they have not turned in work on time or at all. At this point, your student knows that even if they can turn in the mountain of work that has piled up in your class (and probably in other classes as well), that work will only result in a 50% at best. They often think, “What’s the point of turning it in at all?”

What are some next steps to move forward?

- Explicitly and routinely teach time management skills, such as weekly goal sheets and how to break down large assignments into manageable pieces.

- Approach students with empathy and curiosity. Instead of making assumptions, it is best to think, “I wonder why.”

- Ensure the deadlines set by you are achievable by all. Often, we set deadlines based on our larger scope and sequence expectations. However, if this lesson is essential for students to learn, then you need to make sure you are allotting the appropriate amount of time for that to happen.

- Be flexible, and engage in student-to-teacher communication strategies. Some students need more time to complete work than others. Encourage students to reflect on and communicate their time needs.

Unfortunately, grading is part of your job. Since you can’t change that, what are you going to do about it? First, it is important to take time to reflect on your own teaching practices and align them to your values. If the grades you assign don’t feel right, they probably aren’t. Second, take a deep look at your grading practices from a critical lens. Look for biases, inaccuracies, and ways you unintentionally punish students through grades. Look for alternative ways to grade that reflect a more holistic approach. And lastly, remember, not everything needs to be graded in order to be assessed. Solid assessment focuses on feedback to create a culture of learning. Little by little, you can help your students embrace their own continuous learning journey instead of grabbing for the grade.

Reflect on your own grading practices. What biases can you identify?

In what ways can you combat inaccurate and inequitable grading in your classroom?

What assessment tools do you have in place that support learning instead of grades?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.