When students move through most school systems, they are taught questions have a singular “right” answer. They learn their performance on tests draws the line between success and failure. And they internalize the idea of a single letter grade defining their experience in class.

But a growing body of research and literature reminds us, if anything, failing and picking themselves back up actually leads to our students building resilience and problem-solving skills essential to life. Smith College in Northampton, MA has started an initiative known as “Failing Well,” which aims to “destigmatize failure.” Other universities have similar programs in place, such as Harvard University’s Success-Failure Project. It’s clear, at the college level, the idea of failure as a part of the process is taking hold.

Editor’s Note: As you may have noticed, today we’re welcoming our newest writer to the AOE Team! Raymond Yang is a dynamic secondary art educator with a vast and varied background in the field. We know you’re going to love hearing from him. To learn more about Ray, click here, and please give him a warm welcome in the comment section!

So, how can we begin implementing these habits and lessons in younger students? And specifically, how can the arts play a role in this work?

The Dreaded Question

As art teachers, we’ve all heard the question, “Does this look right?” or sometimes put more simply, “Like this?” more times than we can count. Although I had heard it myself, I was surprised at the number of times my students asked me this at the beginning of the school year.

You see, I had just spent multiple class periods trying to instill a culture of experimentation in my art room. I laid out ground rules:

- We don’t discuss grades for class projects.

- The rubrics (which are provided for every project) prioritize progress and effort.

- Completion of a project is not a requirement for positive feedback and assessment.

I even followed up with several projects specifically geared toward breaking down the deeply embedded ideas around how to do things “right.” We constantly discussed what happened in class through the lenses of experimentation, risk-taking, and the opportunity to fail spectacularly.

And yet, I heard the question.

I expected the resistance that stems from years of programming about the correct way to finish a project, but I was still surprised by how firmly embedded this was in their thinking.

As art teachers, we often encounter the struggle students have with believing they’re not an “art kid,” that they’re “no good at drawing,” or hearing the message from their parents that the arts aren’t something worthy of pursuing as a career.

So, how do we overcome these hurdles? And what does that look like in art class?

Creating a Safe Space to Take Risks

The first thing that has to happen in the classroom is for students to feel comfortable taking risks. This attitude starts with the relationships you develop with them. If students trust the teacher, they’re more likely to take a risk or try something new.

Another thing you can do is make your expectations clear. Highlight ways within the project students can find space to problem-solve on their own. If you hear the dreaded question, “Does this look right?” turn it back to them. A simple, “What do you think?” can go a long way.

You may need to remind students to look at the guidelines and rubrics that have been shared. But ultimately, you can empower them to make their own decisions.

3 other ways you can encourage risk-taking are:

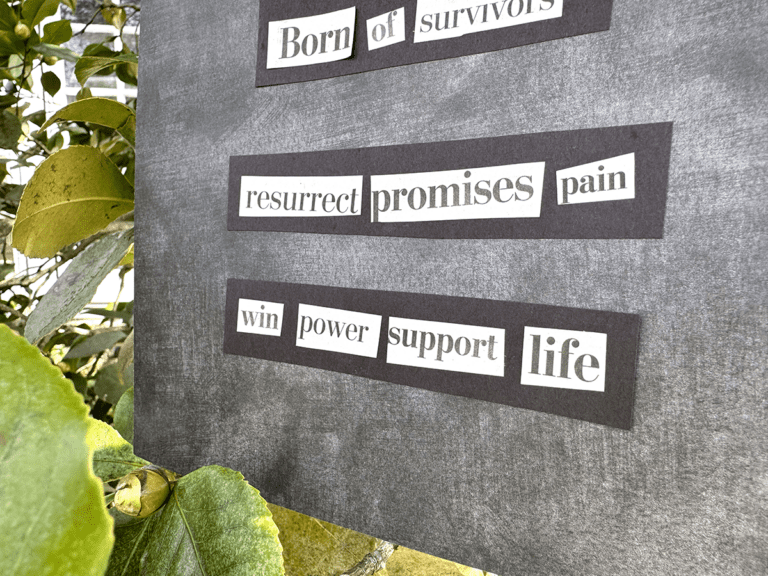

- Allowing students to choose their media in response to a prompt.

- Encouraging students to take projects in their own directions.

- Keeping a dialogue with each student in the class.

In short, a lot of my work comes down to creating a “Culture of Yes” in my classroom (although occasionally that “Yes” becomes a “Yes and…”).

Setting Up Projects that Encourage Pushing into Growth

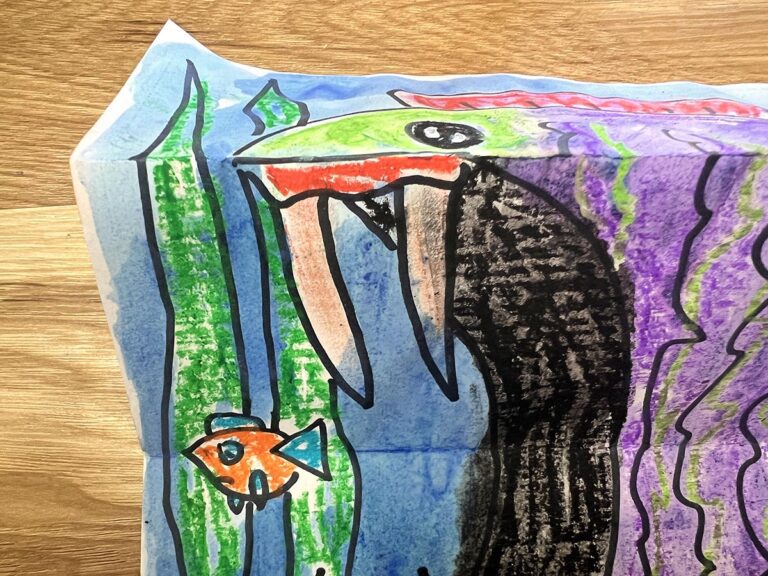

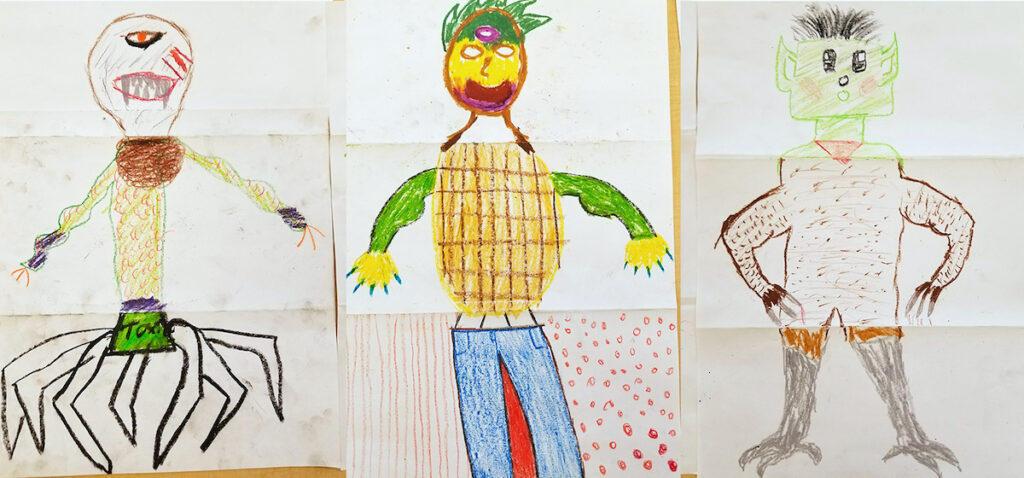

One great way to encourage growth is to start with a series of projects designed so they cannot lead to “perfection” or one “right way.” For example, in my room, the introductory project is usually an “exquisite corpse” collaboration.

Here’s how it works:

- Students fold their papers into thirds.

- The first student draws the “head” and then folds that part over, leaving some indication of where a neck or other continuation of the drawing should occur.

- Students pass their papers to someone new.

- The second student creates a torso and folds that part over. Again, they leave some indication of where the drawing should continue.

- Students pass their papers one last time.

- The third student draws the lower part of the figure.

When we reveal the full drawing, there are always exclamations of laughter and joy. Sometimes students will point out the figures that have randomly assembled into a coherent drawing, but more often than not, the pieces are wacky and goofy.

This exercise encourages both collaboration and the ability to let go of their work. There is no control over the final product, and I push them to get as creative and silly as possible (not a tall order with most sixth graders).

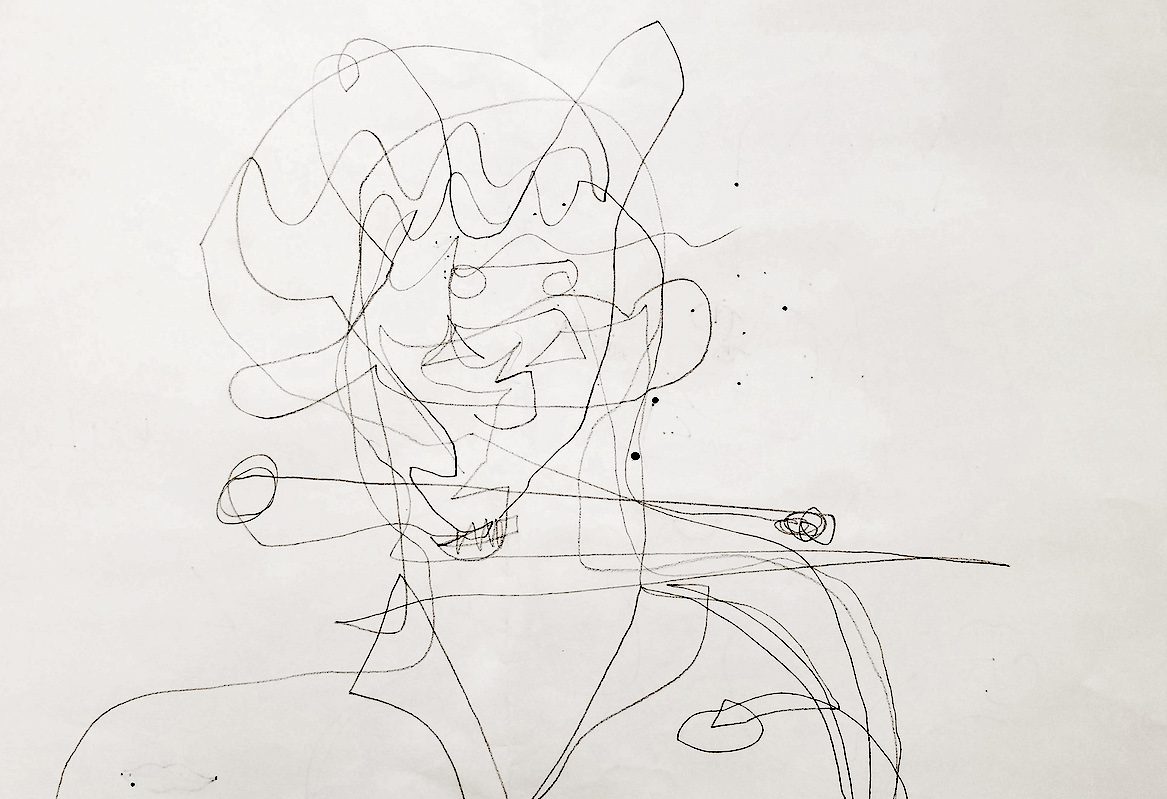

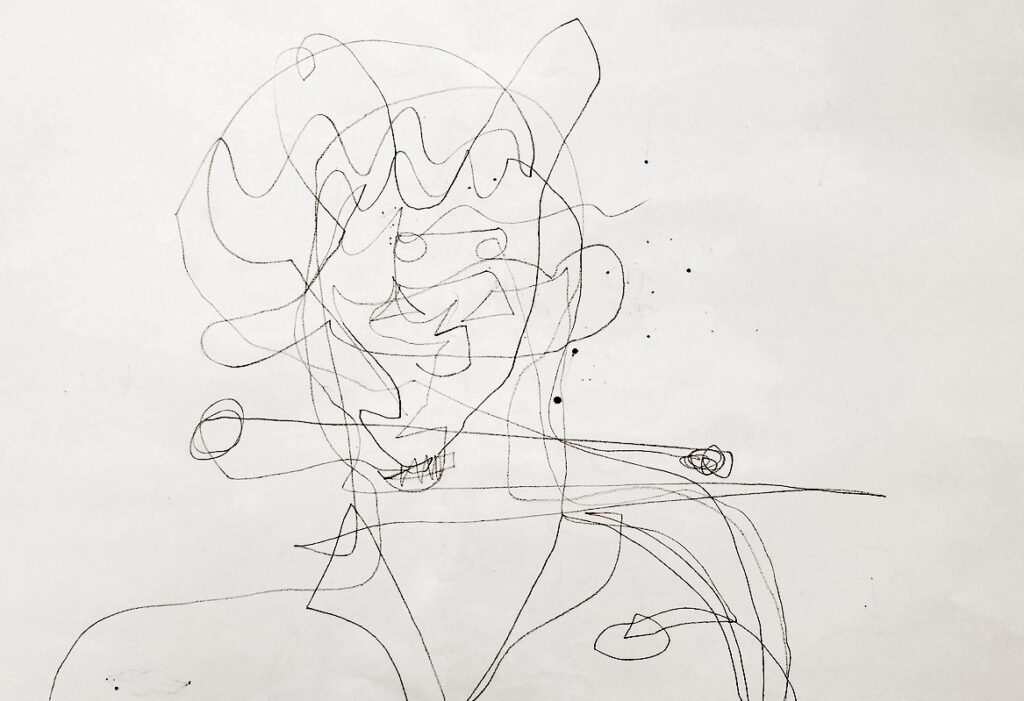

Another project I do early on is a series of blind contour drawing portraits. Blind contour is a great way to develop drawing skills without aiming for any sort of likeness.

When I introduce this project, I typically get a lot of groans and questions. Students express frustration that they won’t be able to “do their best, ” or the portrait won’t come out “right.” I reassure them any portraits with perfect representations of their subject will actually be the ones that haven’t been done “correctly.” And we dive in.

During the exercise, there are usually apologies about how poorly the subject will look in their portrait, but I also get a fair amount of laughter and positive feedback. At the end, we reflect on things noticed while drawing. Often someone will comment on how uncomfortable it made them feel not being able to look down at their paper, and it’s exactly this feeling of discomfort I want them to experience. They are breaking down the habits of “right” and “wrong” and learning to let go.

Building in Time for Reflection

Building in Time for Reflection

So, students have failed spectacularly on a project. Now what? Without some time for reflection and, depending on the project, some moments for revision and re-creation, all this risk-taking is for naught. I have my students reflect through a combination of informal popcorn-style class feedback, exit slips, and classroom discussions and critiques. Giving the students a chance to slow down and look back at what happened is immensely important and rare in a culture that rushes us from project to project. Build in the time to breathe and reflect.

It’s important to teach students to view mistakes as gifts. They open up unexpected doors and pathways that can lead to new insights and approaches to a piece of artwork. When they truly embrace the concept, it creates space for innovation and an understanding that what we originally set out to accomplish might not be where we end up, and that’s ok. Personally, I want my students to see, acknowledge, and embrace their mistakes. It’s only then they can take advantage of them and use them to grow and change.

How have you created space for your students to take creative risks in your classroom?

What projects do you think work best to encourage student growth?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.