Teachers often remark that grading is their least favorite part of teaching. It can be time-consuming and may seem ineffective. However, for most students, high school grades have a serious impact as students inch closer to graduation in pursuit of higher education. So what exactly should we consider when grading student art?

One thing to keep in mind is that students are individuals. Sometimes what’s “fair” isn’t always equal.

Let’s share five important things to consider when developing your grading practices at the high school level.

1. Consider your student population.

We all have our own unique set of students and circumstances. It is important to identify the students you work with and the type of program you’re running. Are your students in an AP class of their choosing? Are your students in a mandatory art class with little or no prior art experience? The goals of your program, and ultimately the goals of your students, are essential for the grading structures you create.

If you are teaching an AP art course, students in your class are likely talented and interested in pursuing a career in the arts. With this in mind, it is important to align your assessment requirements with AP portfolio scoring guidelines. Other advanced classes may place more emphasis on design and technical execution. On the flip side, if you are teaching a population of students with limited prior art experience, you might need to assess other aspects such as growth, process, and content.

2. Consider individual growth.

Grading student growth means a student is not competing against his or her fellow classmates when comparing the process and product. Rather, students are competing against themselves to advance knowledge, skills, and process. Grading students based on their own personal skill levels and growth is about equity.

Let’s look at it like this: Two students walk into your art class. Student A is extremely talented and creating dynamic art pieces comes naturally. Student B has no art experience, has meager coordination skills, and struggles creatively. The final products of these students’ assignments will be vastly different. It is important to grade these two students, not in competition with one another, but in competition with themselves. In other words, grading students based on growth over time is an important consideration to create a level playing field for everyone.

3. Consider the process.

Two aspects of the creative process to consider during assessment are time management and individual work ethic. Time management references the amount of work time a student uses on an assignment. Closely related to this is the work ethic or the effort a student shows throughout the project.

Consider this scenario: In a ten-day assignment, Student A spends three days on the work and seven days distracted by conversations with peers. Student B spends all ten school days on the assignment, working hard. Student A has a visually appealing piece that meets the requirements of the assignment. Student B has more of a developing piece that mostly meets the requirements of the assignment. Which student gets the better grade in the process categories? If you are considering work ethic and time management, the answer is Student B.

Keep this in mind: Student A had ten days to do an assignment and only used three of them. Student A had the time and opportunity to complete three art pieces and could have chosen the best one for submission. Instead, Student A wasted over half of the time. That is not a work ethic that should be rewarded. Student B spent more time and effort in creating only one piece, but the amount of focus, dedication, and work ethic spent on that one piece were far greater than Student A.

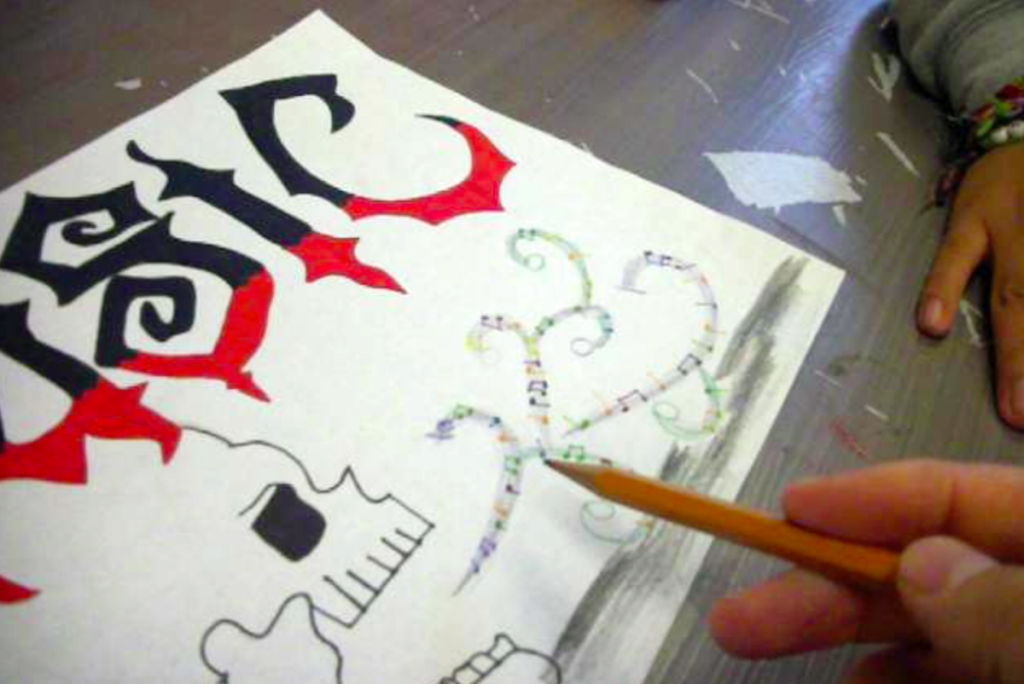

There’s also a grading difference between being stuck and being off-task. Even when some students are stuck, they can experiment with sketching and drafting, engaging in doodles, and researching ideas, as opposed to completely wasting time.

4. Consider the content.

What are the requirements of the assignment? Do students have to use artistic conventions? Are they incorporating something symbolic? Are they asked to implement a color scheme? Instead of grading the overall product as one grade, consider the student’s understanding of the content. While a particular student may struggle with one area of the rubric, they may excel at another.

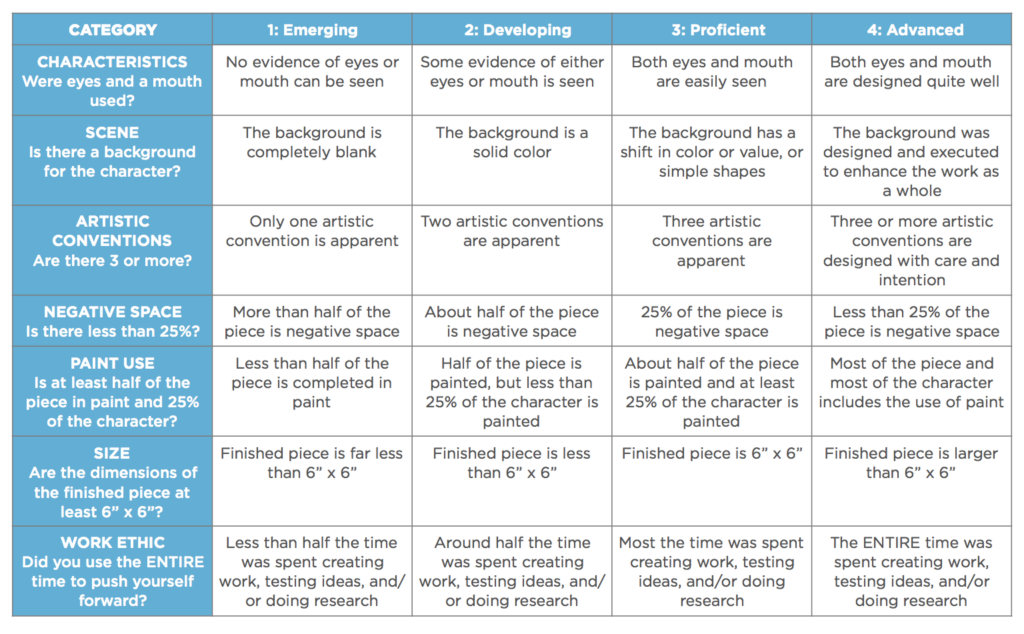

Rubrics are useful tools for assessing work. Growth, time management, and work ethic are examples of grading considerations for potential categories on a rubric. When grading content, the grade is not only about the execution of the technique, but the thinking that went into the decision-making. Effective use of symbolism, idea communication, or composition choices could also be assessed within the work.

Here’s a sample rubric I use in my classroom. Feel free to download a copy for inspiration.

5. Consider self and peer assessment.

A rubric is a useful tool for students and teachers to use in grading work. Before the work comes to you as the teacher, why not let peers and the individual students assess their own work first? Sometimes we worry students will just give work a perfect score, so what’s the point? I challenge you to try it once and see. One or two students may give themselves a perfect score when that is nowhere near warranted. However, in my experience, the majority of students will be extremely honest with themselves and each other in assessment. In fact, many times students will grade themselves lower than I would as the teacher.

Self and peer review can open dialogue between peers as well as with you. This sets up a wonderful opportunity for one-on-one conferencing about a final grade. Students and teachers can compare reasoning for grade choices, which can provide meaningful feedback and learning opportunities.

Grading can be a daunting task. It is important to consider the program you run and the students who are in it. Personal growth, time management, individual drive, content understanding, and multiple people assessing work can establish more holistic and meaningful grading for all your students.

What is your grading philosophy?

What do you agree or disagree with in this article?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.