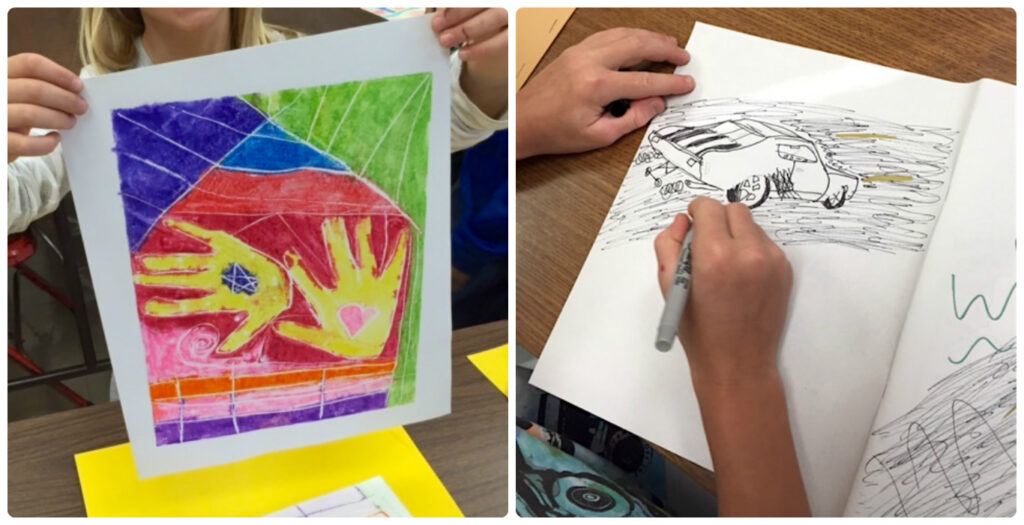

Teaching concepts with TAB is easier than you might think. In fact, once your classroom is up and running with functioning centers your students have learned how to use, it’s easy to plan and teach lessons that meet any standard. In TAB classrooms, new content is mainly introduced through short lessons at the beginning of class called “mini-lessons” or “five-minute demos.” These are kept short so kids have lots of time to investigate new concepts.

One of the best things about TAB is that, because students generate their own ideas, you have lots of time to talk with students during work time to help them connect concepts to their personal artwork and assess learning.

The following unit is organized around National Visual Arts Anchor Standard 1: Generate and conceptualize artistic ideas and work. This concept is covered over three weeks, with content introduced during mini-lessons, then examined and assessed as students work in centers. It’s written for TAB classrooms that are up and running, with centers that kids know how to use.

Artists are Inspired Unit

Age Range: K-2

Goal: Students will exemplify idea generation through work process and discussion.

Class 1: Introduce the Idea of Inspiration

Teacher Input: “Over the next few weeks, we are going to learn about how artists find ideas. Finding an idea is called inspiration. It’s a good, excited feeling, like knowing the right answer. What kinds of things inspire you to make art?”

Lead the discussion making a list on the board as students share ideas. Then tell students, “These are all great ideas. Today as you work in your centers we will talk about inspiration.”

During Work-Time: Circulate around the room and talk to each child about their ideas. Ask them to tell you about what they’re making and where they got the idea.

Assess student responses, looking for the following:

- Can the child explain where he or she found inspiration for their work independently or do they need assistance?

- Is evidence of inspiration evident in their artwork or process? Are they creating based on a recognizable theme, idea, or source? For example, artwork about the theme of “family” or a book they’ve read would qualify.

Closure: Think, pair, share. After students clean up, ask them to think about what inspired them. Pair them up with a “shoulder partner” to share what they thought about.

Class 2: Show Different Artists and Talk About Inspiration

Teacher Input: “Today we are going to continue to talk about inspiration, or where artists get ideas. Sometimes artists are inspired by things that they are interested in.” Next, share an artist with the class and have a short discussion about what the artist is interested in. Some examples of artists that could work for this, and there are many, are Georgia O’Keefe, El Anatsui, or Zaria Forman. Next, ask students to talk to their table groups about things they like and how they could use them in their artwork.

During Work-Time: Circulate around the room and talk to groups about their ideas. Ask who is making art inspired by something they are interested in. Make sure to check in with students who were unable to vocalize where they got ideas from in the last class.

Once again, look for things like:

- Can the child explain where he or she found inspiration for their work independently or do they need assistance?

- Is evidence of inspiration evident in their artwork or process? Are they creating based on a recognizable theme, idea, or source?

Closure: After cleanup ask the class, “Who made artwork today that was inspired by something you’re interested in?” Call on a few students to share their artwork and inspiration with the class.

Class 3: Talk About How Inspiration Can Come from Life Experiences

Teacher Input: “We’ve been thinking about the ways artists get ideas for the last few class periods. We’ve learned about what inspiration is and how artists can be inspired by things they are interested in. Another way artists are inspired is by experiences or things that happen in their lives.”

Next, share one or two artwork examples with the class for a quick discussion. Faith Ringgold’s art is perfect for this lesson. Talk about how the artist used personal experience for inspiration, then ask kids what kinds of personal experiences they might be inspired by.

During Work-Time: Circulate around the room and talk to groups about their ideas. Ask them why knowing about inspiration is important. Also, make sure to check in with students who were unable to vocalize where they got ideas from in the last classes.

Again, look for the following:

- Can the child explain where he or she found inspiration for their work independently or do they need assistance?

- Is evidence of inspiration evident in their artwork or process? Are they creating based on a recognizable theme, idea, or source?

Closure: After cleanup ask the class, “I asked you why it’s important to know about inspiration while you were working today. Who would like to share your ideas?” Call on a few students to share.

In Summary

The three class periods spent thinking about inspiration will help your students internalize this concept. In addition, applying new learning to their own work and process will give them deeper knowledge by building personal connections. Not all students will be able to verbally explain their thinking about finding ideas in the first class, but by talking it through with them and providing subsequent chances to try again, the vast majority of students will be successful.

Of course, a verbal explanation is just one form of assessment. If a student is unable to speak about inspiration, use your assessment of their art-making process or work to assess their understanding. Once your students have internalized the concept, make it a part of the language of your classroom.

What types of units do you teach in your TAB classroom?

What information do you want about how TAB works?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.