By definition, a theory is not a fact. Yet, we often teach color theory as if it were irrefutable: Red, yellow, and blue are the primary colors that make up all other colors. Two primary colors make a secondary color. A primary plus a secondary makes a tertiary. And on it goes.

While this theoretical structure is useful for the organization and manipulation of color, the simple fact is red, yellow, and blue do not make every other color. What we were taught, and what many of us teach our students, is not completely accurate.

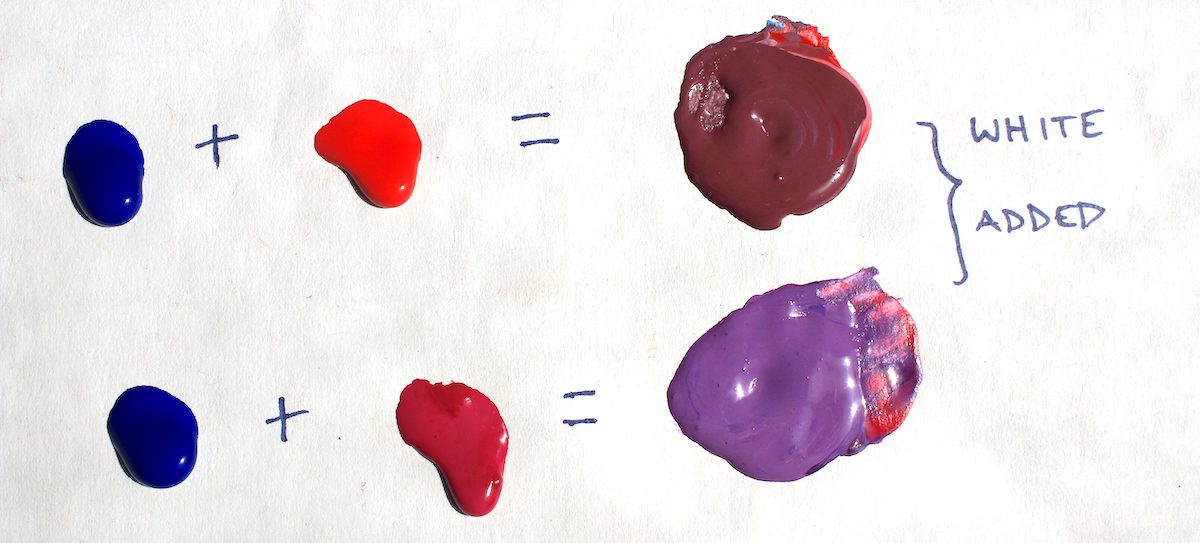

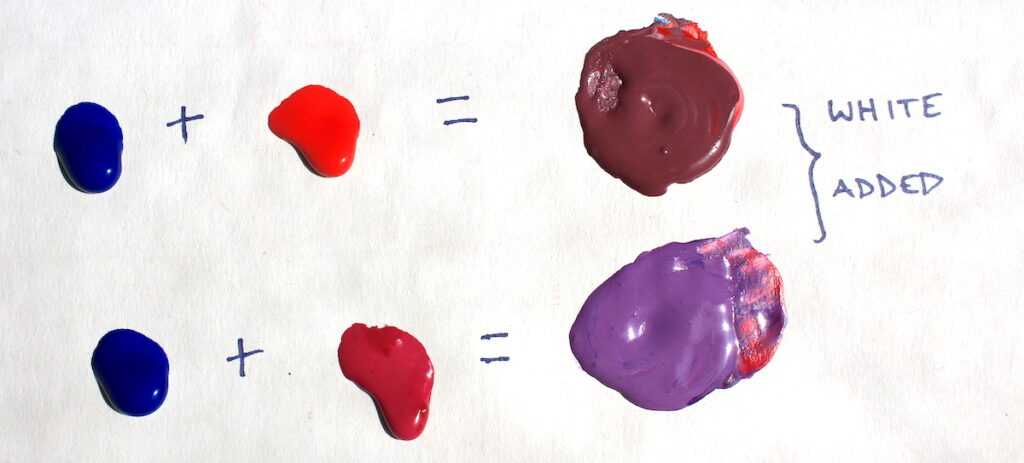

I realized this early in my painting career. For me, mixing red with blue produced a browned-down version of violet. Most of us have had this experience and can agree without magenta, having a clean, vibrant violet is impossible.

So Why Do We Insist on Three?

Three seems to be a magic number. We structure a lot of our understanding of art and reality around the concept of a triad. We have three primary colors and group colors into primary, secondary, and tertiary. Of course, there are also warm, cool, and neutral colors. Plus, we perceive reality in three dimensions of length, height, and width. As teachers and artists, we break concepts into line, shape, and form along with value, tone, and hue. There is the “rule of thirds” as well.

Outside the world of Art Ed, our government system, public school institutions, and even many religions use the number three to categorize and describe branches, levels, and concepts. The number three, and multiples of three, have become the fundamental schema from which we develop our understanding of reality.

The Importance of Structure

There are different camps in color theory. In both an article and an enlightening podcast interview, Tim Bogatz explores opposing perspectives. Many people feel cyan, magenta, and yellow should be seen as the new primary colors. Other people believe three is not the correct number for primary colors to fully embody the realm of color potential.

Regardless of your point of view, there is value in using the traditional color theory model. Students can grasp the concept of three primary colors making a six or twelve-color wheel. The color wheel provides an understandable model for discussing complementary, analogous, warm, cool, and neutral colors. The color wheel, based on red, yellow, and blue, should not be completely discarded. It can serve as a great way to explain to students one of the many reasons why we call color a theory, not a fact.

Implications

But does it matter which view of primary colors we choose? Is there harm in having multiple primary color combinations? What implications do these color theory debates have for our classrooms? I have heard many art teachers say, “Art is all about breaking the rules.” If this is true, then we must examine and challenge the previously established artistic norms, structures, and knowledge.

Students are always trying to break rules and disprove systemic understandings. When we are open with our students and tell them the primary colors in painting are unable to make every color, then we share a sort of rebellious knowledge. Explaining color is a theory not a fact and there are debates within the artistic community about primary colors, encourages students to make their own analysis and form their own opinions. It is also a way to invite students to challenge other forms of established “truth” humans believe but have yet to prove.

Traditional color theory is incredibly important. It’s valuable to use red, yellow, and blue to help students build basic knowledge. However, showing students how a theory can be challenged is even more important. Thinking creatively about accepted norms and theories is something at which artists excel. Showing our students there is more than one way to think about things will broaden their worldview and increase their capacity for critical thinking. Give your students the ability to question what you teach them. It may open up new avenues of interest and promote the journey of lifelong learning.

Which primary colors do you teach in your classroom?

How else do you teach students to challenge conventional ideas?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.