There are some artistic traditions toward which art teachers gravitate. Australian Aboriginal art seems to be one of those. But, how much do we really know about this art form? And what about contemporary Aboriginal artists? I recently came across some information that challenged what I had previously known.

It all started when I began corresponding with Julia Sutton, who works for the Japingka Gallery in Western Australia. Not only does the gallery represent a large number of contemporary Aboriginal artists, but it also devotes a lot of time and energy to educational outreach. In fact, a portion of Julia’s job is to interview Aboriginal artists before their exhibitions. I would love to share what I learned during my exploration.

It’s time to revisit, research, and revamp our understanding of this unique cultural art form!

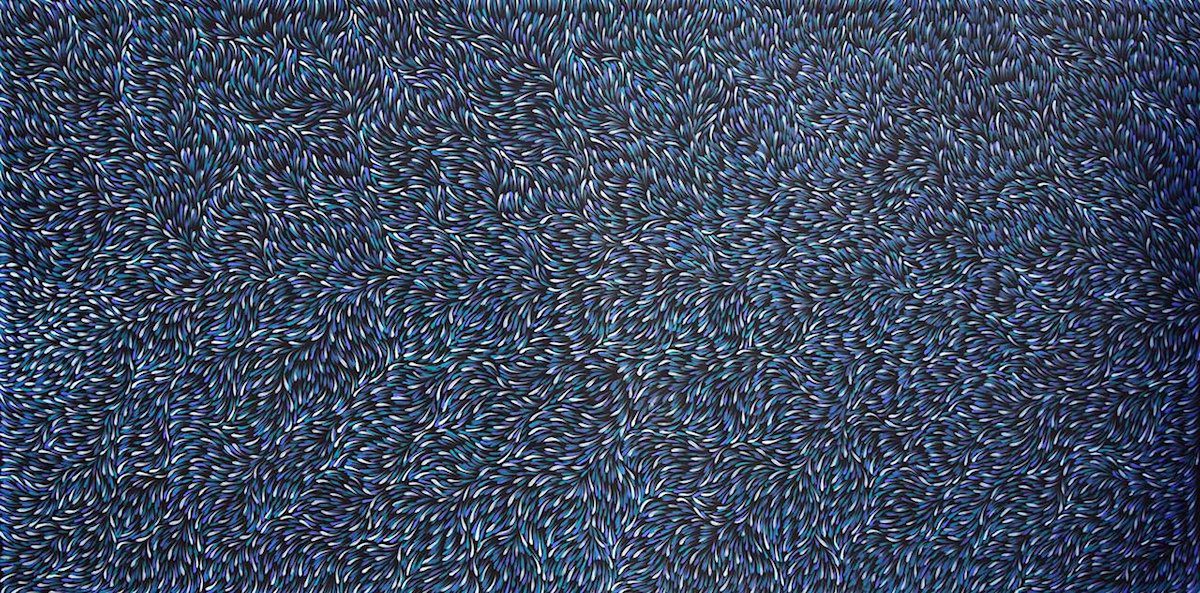

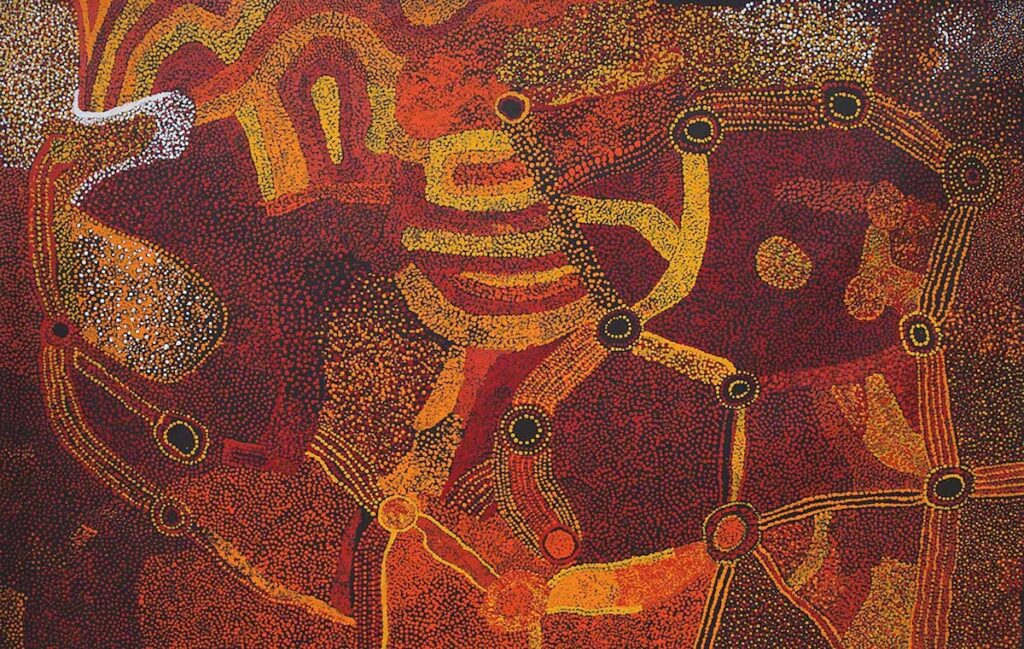

image via Japingka Aboriginal Art

Aboriginal Art Revisited

Before we dive in, let’s talk briefly about the history of Aboriginal Art, starting with this breaking news: Did you know that recent archeological finds have challenged the Eurocentric idea of art developing in Europe and radiating outward? It’s true! These discoveries place some of the world’s oldest artwork in Indonesia.

What’s more, Indonesia is in close proximity to Australia. (This article is a fascinating read on the connection between the two.) Add to these facts that the Aboriginal people have lived in Australia for a minimum of 65,000 years, and we begin to understand that a much bigger story is taking place. Clearly, we have an artistic tradition our students need to learn about! But we need to make sure we deeply understand and correctly present both the past and present to give our students the whole picture.

The Basics

The Aboriginal people are the original indigenous people of Australia, who lived on the continent long before European colonization. Aboriginal artists are known for their sophisticated ancient rock art, body painting, bark painting, and their acrylic dot paintings. Aboriginal styles are distinctive and closely linked to cultural belief systems.

Dot Paintings and Dreamtime

While Aboriginal art can vary, most Aboriginal art lesson plans taught in art classes seem to focus on the dot painting style known as the “western desert style.” These paintings are usually connected to the Aboriginal belief of Dreamtime.

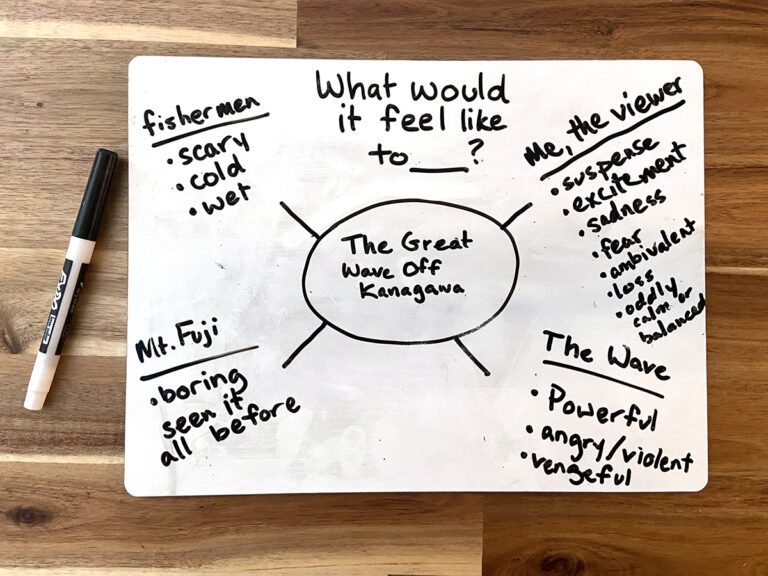

Dreamtime is the sacred creation story of the planet, passed down through generations through songs and chants. In these creation stories, Ancestors helped form the people, animals, and topography of the land. The Japingka Gallery blog goes even further, to explain, “the Ancestors are the initial creative forces who brought into being all the features of the land, of animals and the natural world, of people and the Law, and the totemic connections between all of these. The Dreaming or the Dreamtime is a sacred narrative of Creation that is seen as a continuous process that links traditional Aboriginal people to their origins.”

Aboriginal artists use symbolic representations within these Dreamtime stories. Many of these symbols are sacred, and the artists were “negotiating what aspects of stories were secret/sacred and what [was] in the public domain.” Thus, dot painting began as a way to subvert the image, maintain secrecy, and to fill the background.

Subject matter in these beautiful artworks varies but often includes symbols of the Dreamtime, symbolic animals, and natural elements (like food/plants, water, or weather). All of these subjects are accessible for younger students.

If you’re looking for even more ways to help make art history meaningful for your younger students, be sure to check out the Art Ed PRO Learning Pack Make the Most of Art History in the Elementary Art Room. You’ll learn how to choose the perfect artists, themes, and projects to infuse art history into your curriculum and explore a wide variety of instructional strategies that help engage students.

Available Resources

To avoid cultural appropriation, try to stick with educational materials created by Aboriginal artists instead of those found elsewhere.

Here are two good places to start:

- japingkaaboriginalart.com

In addition to the artwork (which can be searched by theme, animal, etc.), this gallery maintains a beautiful blog. Even better, they provide authentic and specific lesson plans you can implement in your classroom right away. - Stories from the Billabong by James Vance Marshall and Francis Firebrace

This book tells stories from the Yorta-Yorta people, and both the contributing text and illustrations come from an Aboriginal author/illustrator.

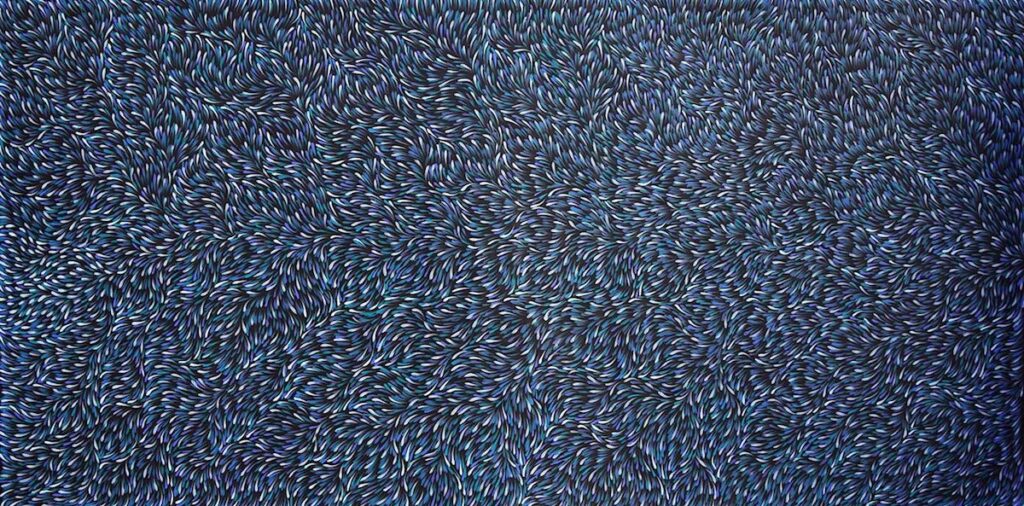

image via Japingka Aboriginal Art

Aboriginal Art, Researched

The number of quality resources that the Japingka Gallery has developed for teachers is staggering. As I combed through their blog, articles, and lesson plans, I was fascinated by the aspects of Aboriginal art of which I was previously unaware. Here are two takeaways Julia and one of the directors, David Wroth, helped me unpack.

1. The Transition to “Western Materials”

Symbolic painting has a long tradition in the Aboriginal culture, namely in prehistoric rock art. However, the use of acrylics on wood and canvas is fairly new in Aboriginal art; it has only been happening since the 1970s. So, although the culture is ancient, this type of art is not!

The iconic dot painting we have come to know is frequently called the Papunya or Western Desert style. Interestingly enough, Papunya was a movement partially motivated by a school teacher, Geoffery Bardon. Through his work with Aboriginal school children, Barton helped initiate some important conversations within the larger Aboriginal community. Eventually, this resulted in the Aboriginal culture being shared with the outside world, through painting.

As the Japingka blog shares, “the contemporary Aboriginal art movement formed away from the Western tradition. It was a way of saying ‘We are the authority, we are the law, and we will explain it in visual terms in these paintings.’ The artists made use of western art materials and hoped there would be an art market for their work.”

From there, many different styles developed and flourished. In fact, the different regions of Australia are home to different types of painting. One especially exciting portion of the Japingka galley’s site is a comprehensive index and explanation of the regions, complete with visual examples.

2. More than Dreamtime, the Song Lines

Almost all of the Aboriginal inspired lesson plans I have encountered include the Dreamtime, but it turns out to only be a fraction of the story! Aboriginal people believe they cannot own the land. Instead, they are charged to care for it, as “custodians.” Part of your custodial duty is to learn the traditional stories specific to your region, through song and chant.

As Director, David Wroth, explains for the Japingka Gallery, “In Aboriginal culture, these ancestral sacred stories are passed on as large song cycles. People might specialise in chapters or sections of a songline which tells the entire creation story that relates to a particular tract of land. People on neighbouring land will have the next chapters of what happened to the ancestors as they crossed over to their own part of the country.”

Although many of the Songlines are still considered to be sacred and secret, paintings are made from their symbolic imagery. This idea, of the artist as a collaborative piece of a larger whole, is an intriguing aspect of Aboriginal culture.

image via Japingka Aboriginal Art

Aboriginal Art, Revamped

After revisiting and researching, here are some new ideas to revamp the study of Aboriginal art with your students.

1. Strive to acknowledge individual artists, not just a cultural art form.

When teaching multicultural art, there is sometimes a tendency to focus on the “other” as a whole group. Combat this impulse by speaking about individual artists. When we explore painting in the Western tradition, we honor the makers as individual artists by name. Why shouldn’t this be true of Aboriginal artists as well?

As the Japingka Gallery explains, “Few traditional Aboriginal artists sign their canvases on the front of the painting – the content of the painting is in many ways the artistic signature of the artist, as it is restricted to just a few authorised individuals to paint.”

The custodianship of a particular area serves as an identifier. So, a lot of artists do not sign their work. But, that isn’t to say there aren’t well know artists in the Aboriginal art world.

Start with the work of Albert Namatjira, who is probably the most famous Aboriginal painter. As a watercolor landscape artist, he depicted his custodial lands with great beauty and skill.

Then, explore the dynamic and varied artwork being curated by artists from the Japingka Gallery and other legitimate sources.

2. De-emphasize animals and re-emphasize personal spaces and places.

While many contemporary aboriginal artists do depict Australian animals, we must be careful to avoid distilling this rich and beautiful tradition down to just dot paintings of native animals. It is so much more meaningful, and the subjects are much more deeply varied.

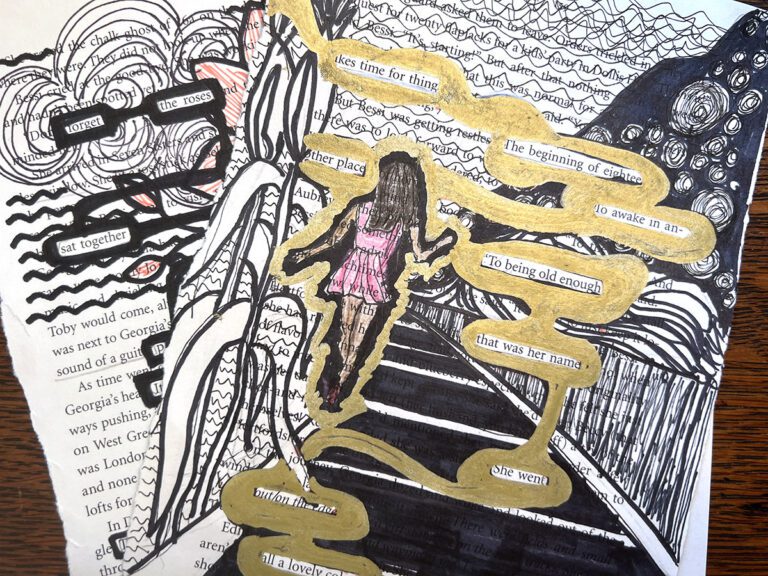

At its core, Aboriginal meaning-making through art is about preserving a secret and sacred cultural history. It is also about honoring the stories of the place they have called home for thousands of years. Instead of promoting copying, explore using these themes of secrecy and symbolism related to places your students know well.

3. Connect with your music teacher.

Australian art has a deep connection to songs and chants. These are the vehicles with which the Songlines transmitted the Dreamtime stories for generations. Many aboriginal artists sing and paint simultaneously, as one creative outlet inspires the other. The opportunities for cross-curricular connections with your music faculty are endless. Reach out to your music teacher to see what support they could offer for your Australian art unit.

4. Explore ideas of interconnectedness.

As we search for ways to use cooperative learning in our classrooms, consider its relationship to Aboriginal art. Aboriginal songlines rely on individuals to learn and perform specific portions of a larger story. Each person contributes a part that connects to a larger whole. Consider conceptual applications of this idea. For example, you could have students create their symbolic artwork as parts of a whole, where pre-determined edges hook together to make a collaborative finished piece.

Now that we have revisited, researched, and revamped our understanding of Aboriginal art, we can implement more genuine learning in our classrooms. With so many authentic resources available, and so many potential avenues for conceptual connections, it is easy to start integrating Aboriginal art into your teaching.

Special thanks to Julia Sutton, David Wroth, and the Japingka Gallery for sharing their expertise with us!

What lessons have you taught incorporating Aboriginal artwork?

What are your favorite Aboriginal resources?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.