Connections across the curriculum add value to students’ learning experiences. In seeking to make connections, it is not unusual for teachers to engage students by creating personal timelines, family trees, and art activities based on cultural traditions. After all, understanding how culture shapes individual identity, values, and worldviews are core issues in the arts and social sciences. Teachers have good intentions; they seek to help students recount experiences, deepen their understanding of time, history, and culture, and build empathy.

A variety of encounters and changing contexts caused me to question the goals of several art lessons and units, especially some I used because they felt familiar and satisfying. I began to ask myself:

- How do art assignments regarding the concept of “home” affect students who are homeless? Or highly mobile? Or students who feel unwelcome or unsafe in their own home?

- How do art assignments that draw upon personal or family history affect students who have experienced loss? Or separation? Or incarceration?

- What do art assignments based on immigration narratives mean for students who are indigenous? Or African American? Or undocumented? Or refugees?

We should embrace art and units of study that engage with individuals’ stories, community, or history because art humanizes.

However, it is also important to ask: Can we study these topics through art, while taking a trauma-informed approach? Can it happen in a way that makes students feel safe rather than exacerbate their trauma?

Taking A Trauma-Informed Approach

Trauma happens when a child feels threatened by an event they are involved in or witness to. As contributing author Lisa Kay points out in the edited book, Art for Children Experiencing Psychological Trauma, children are typically exposed to at least one traumatic event by the time they are sixteen. Trauma can range in its severity and duration. Students and their families can also experience historical trauma. Historical trauma is when members of a specific cultural or racial group continue to feel the ongoing effects of violence or oppression.

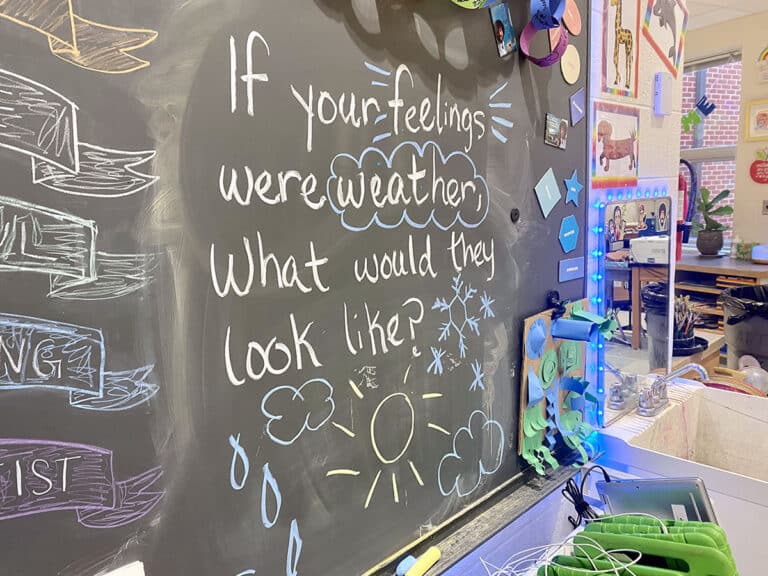

In her article, “Trauma-Informed Teaching Strategies,” Jessica Minihan explains that in a trauma-informed approach to education, “Teachers are proactive and responsive to the needs of students suffering from traumatic stress and make small changes in the classroom that foster a feeling of safety.” For art teachers, these thoughtful changes might include:

- Being specific about relationship building. For example, rather than asking a student, “How is your day going?” chat about their favorite sports team or video game.

- Expecting unexpected responses and learning to watch for personal and environmental triggers. For example, entering a noisy room with fluorescent lights and piles of supplies on the tables might trigger a student dealing with a chaotic home life.

- Allowing students to demonstrate competence. For example, allowing an interested student to tinker with and fix a broken tool could lead to a feeling of accomplishment.

Rethinking Units With Trauma-Informed Teaching In Mind

Further unit or lesson specific adjustments for art teachers might include:

- Offering choices, especially in art assignments that require personal disclosure.

- Letting students choose to reframe narratives if they want to. While art educators are responsible for engaging students in social issues, this may not be what every student needs at a given moment in time.

- Flexibility in reflection and assessment.

As you prepare for a unit or lesson involving themes such as the individual, family, or culture in art, consider the following possible shifts in approach:

Offer an option to make biographical art about someone students admire.

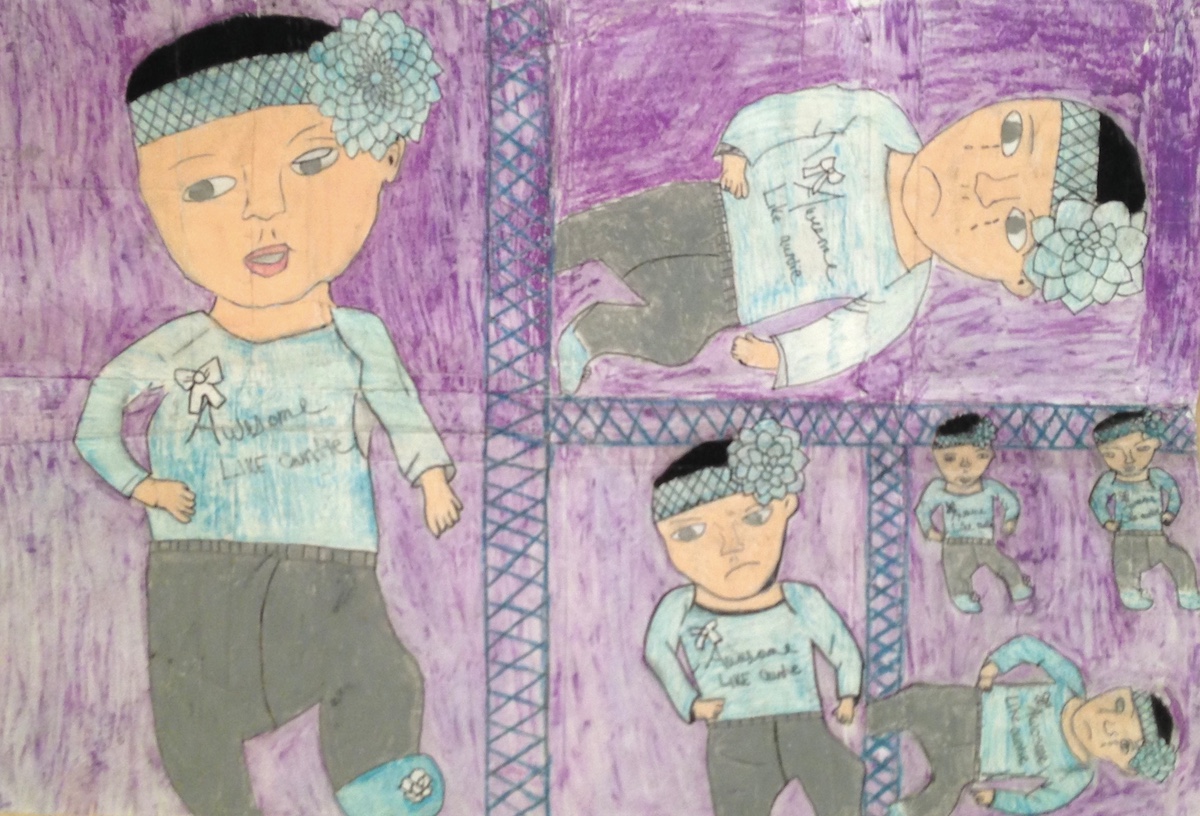

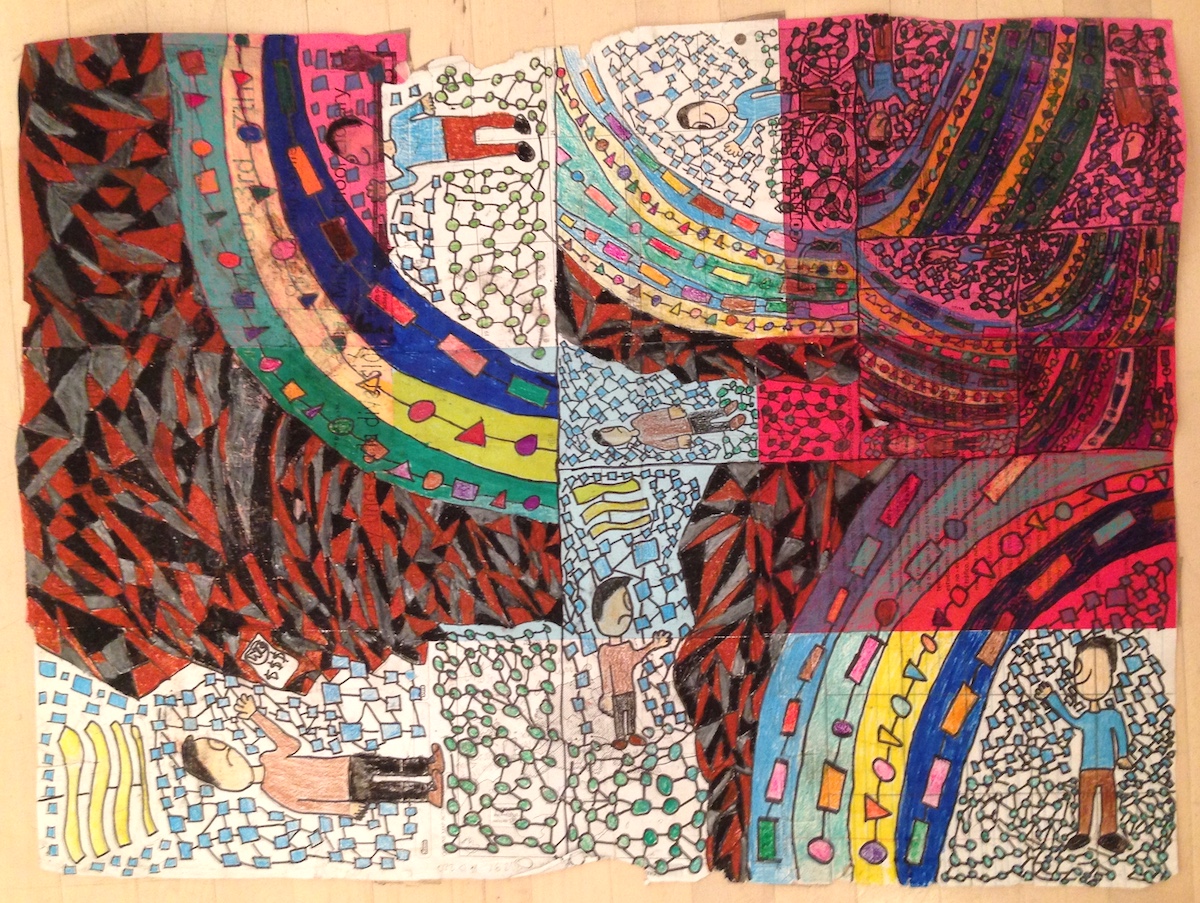

Self-portraits and self-reflection are great subjects for artists seeking to make sense of themselves or help viewers understand a specific point of view. However, students can also work toward these same goals by making art about other people. Students can reasonably investigate historical figures, celebrities, or local leaders from third grade forward and teach viewers about what they learned through their art. Making biographical art about other people still offers opportunities to empathize and learn about life journeys. Offering this choice recognizes not all students are ready or want to share their personal stories. Rather than an emphasis on personal vulnerability, the emphasis is on students’ responsibilities to their subjects and their viewers.

The Power of Art to Heal Trauma

Normalize making art about a variety of important people and valued relationships.

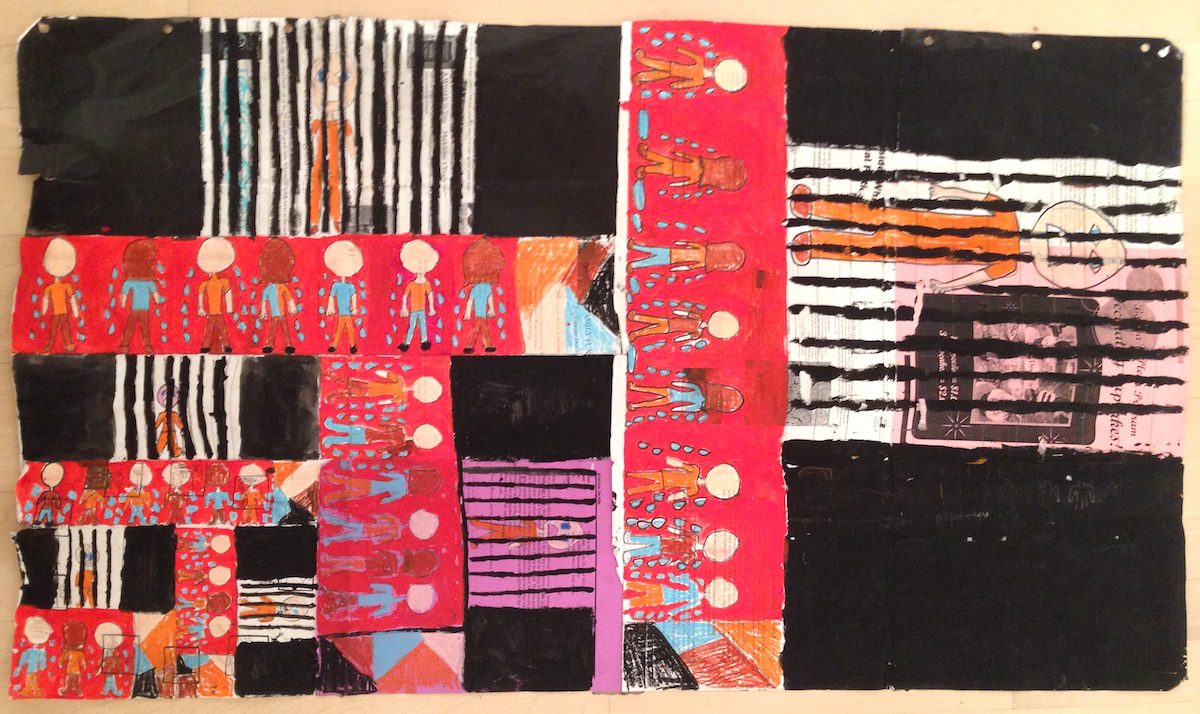

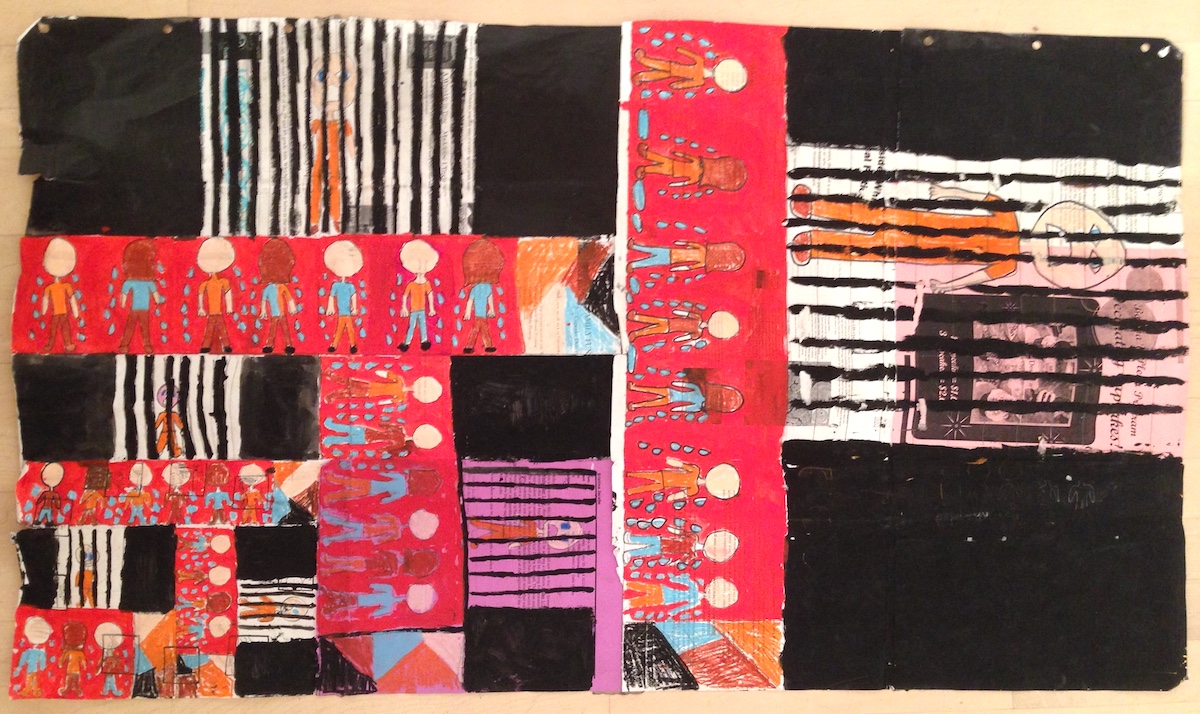

Shortly after young children begin to draw themselves, they draw other people who are important to them. It makes sense then, that figurative art about children and families would be a relatable topic for elementary students. However, families come in all shapes and sizes.

Rather than focusing only on family portraits, broaden the conversation by inviting elementary artists to make art about important people and valued relationships. This approach shifts the emphasis from “Who is in your family?” to “What makes people special to us?”

12 Articles to Support Art Educators and Teaching Social Issues

Show students how and why contemporary artists create artwork based on cultural traditions.

Art can offer insights into cultures and traditions. However, it is important to be aware of the connections students feel with artworks, the stories we tell about those artworks, and the artists or communities that produce them. A way to address this is by pairing contemporary artworks with the historical works they reference. With the added layer of artist statements, you can help students understand how artists knowledgeably reference history and traditions while looking to the future. Engagement with art in this way can become an opportunity for students to reflect, critique, and envision goals.

Making connections to students’ lives has always been—and will always be—an excellent way to build an invaluable teacher-student relationship. As art teachers, however, we must remember we may only see one small sliver of a student’s experience. Practicing trauma-informed teaching is one way to establish a safe, welcoming environment for every artist, and at the end of the day, isn’t that the most important thing we can do?

How can you offer choices to help students feel safe in your art class?

What triggers might you need to be ready to respond to?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.