Keeping students motivated seems tougher than ever right now. Students are more unsettled than usual, and attention spans are at an all-time low. Perhaps projects feel shorter because students are rushing through their work. Maybe your students aren’t applying themselves as well as they could. You may also have noticed an uptick in mediocre projects.

There are a lot of reasons students may be struggling to engage with the curriculum. In creative classes such as art, students may fear they are “bad at art.” As a defense mechanism, they may zone out or not try very hard. Engaging these reluctant learners is key to their success in the art room. By blending surrealism, music, and choice, you can increase student involvement and ownership.

Read on to learn more about the connection between art and music with a lesson plan for all levels.

How can you engage reluctant learners through music?

One of the quickest ways to engage reluctant learners is by incorporating their interests into projects. Recognizing that students are multi-dimensional beings goes a long way toward fostering a connection with your class. Engaging with students about their interests in pop culture is an effective way to build rapport. Like visual art, music is a universal language that can connect all students.

John Hopkin’s School of Education shared studies about how integrating music into the classroom increases engagement at all levels. By capitalizing on most students’ interest in music (and specifically what they listen to in their free time), you will find they are more likely to become engaged in art as well.

Do you want to focus more on motivating reluctant learners? Check out this PRO Pack.

There has always been a connection between art and music.

We see this connection through figures and movements in art history, like the work of synesthetic artist Wassily Kandinsky, throughout the Harlem Renaissance, and in the work of action painters like Jackson Pollock. Musical genres like punk, heavy metal, and country each have their own carefully curated artistic aesthetics. There is an entire sector of the graphic design industry dedicated to designing merchandise for musical artists. To narrow this huge range down for your students, look at pieces from a similar time frame or venue.

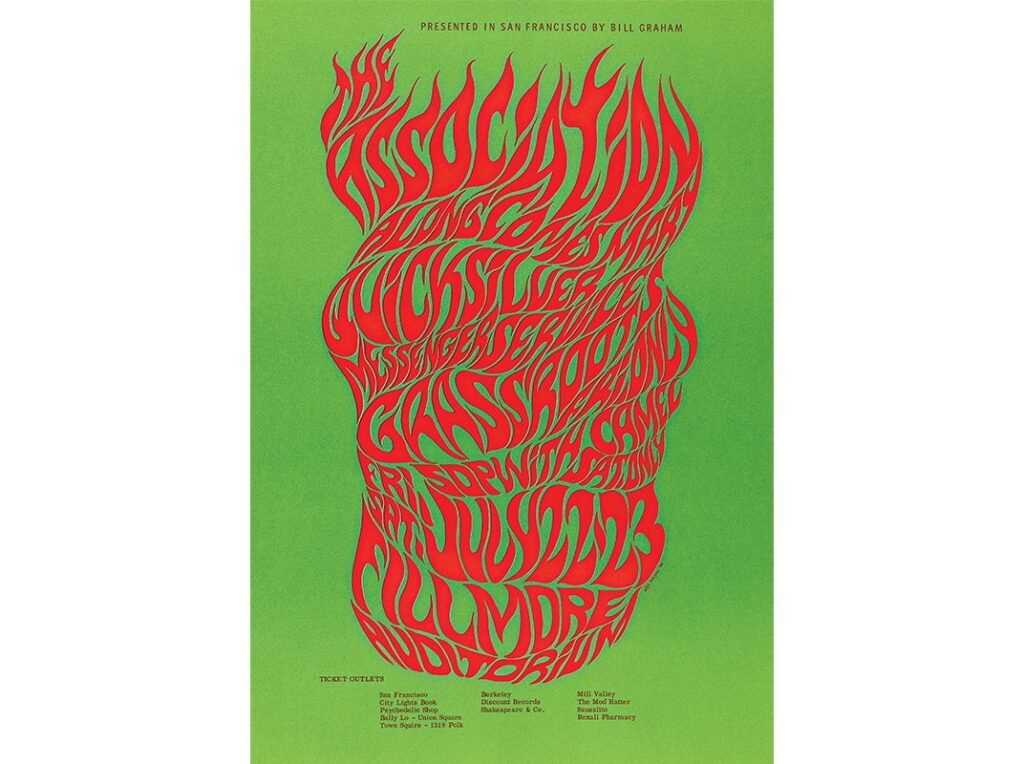

A great example is the Fillmore in San Francisco. In 1966, promoter Bill Graham began commissioning local artists, like Wes Wilson and Victor Moscoso, to create eye-catching, information-filled posters. Graham wanted to advertise upcoming shows for local bands like The Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane. The commissioned posters went up all over town. The public took them down almost as quickly, clambering for souvenirs. It began a Fillmore tradition of printing limited-edition posters for every concertgoer. This tradition continues today under the guidance of Arlene Owseichik. These posters are so iconic; they even have a collection in the US Library of Congress.

Ask your students to research poster designs of some of their favorite bands—maybe they have their own Fillmore poster, album art, social media aesthetic, or merchandise style. Be sure to do some preliminary research and preview each resource before sharing it with students.

For more ideas about bringing music into your art curriculum, check out this FLEX Collection and this episode of Art Ed Radio.

Now let’s talk about surrealism!

This lesson begins with automatic drawing while listening to music. Automatism is a surrealist tenet and means to create without conscious intent. Artists who use automatism may not formally plan their pieces. Instead, surrealists, like Joan Miró and Inka Essenhigh begin creating spontaneously. They allow their creativity to flow through them unadulterated onto the canvas. This might sound intimidating to your students, so remind them it’s likely they have done this before. If they have ever doodled in the margins of their notebook during a lecture, tell them, “Congratulations! You’re an automatic drawer!”

You may find automatism more difficult with older students. According to Scientific American’s column, Literally Psyched, older students have learned to be more fearful about expressing themselves creatively. To encourage older students, draw along with them, so they can watch you create in tandem. Demonstrating that you, the teacher, are producing imperfect work empowers students to do the same.

Interested in more ways you can apply automatism in the art room? Check out this article about creating surreal heart maps and this article about neurographic art for students of all ages.

Do you feel like you need a little more foundational knowledge of surrealism? There is a FLEX Collection for that, too!

Let’s mix these concepts into one project adaptable for all grade levels.

Combining art and music is effective when it comes to motivating and cultivating connections with your students. Let’s look at an art lesson that does just that! You can easily adapt this lesson for different ages and levels. It can also be a quick activity between longer units or expanded to result in a more realized artwork.

Step 1: Practice automatic drawing as a group.

Pick a few school-appropriate songs from different genres. Play the songs as students spontaneously draw. Students consider the elements of art while listening to the songs. Encourage students to avoid specific imagery.

Use the following questions to guide students as they draw:

- What lines could represent the beats?

- What colors do you hear?

- Does the song sound like it would be made of organic or geometric shapes?

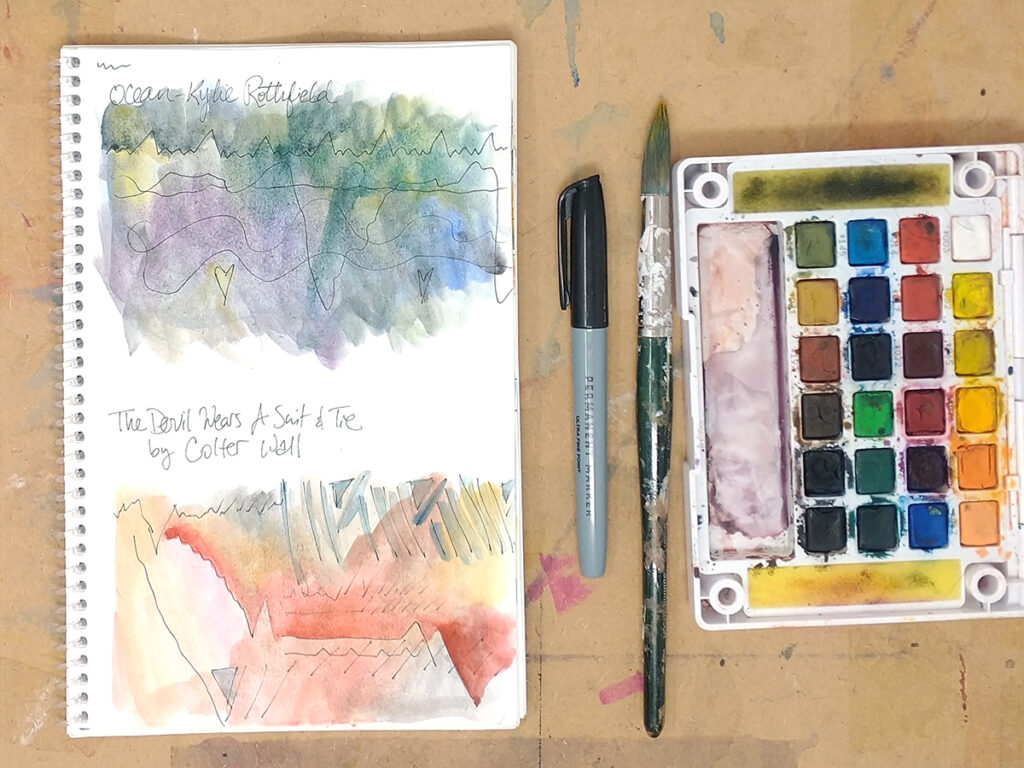

The above examples used the songs Ocean by Kylie Rothfield for the top drawing, and The Devil Wears a Suit and Tie by Colter Wall for the bottom drawing.

Step 2: Students select a song of their choice.

After students are comfortable with automatic drawing, they create a larger drawing with a final song. If you have elementary students, you may want to provide a list of pre-approved songs they can choose from.

Step 3: Demonstrate how to use viewfinders.

Show how to use a viewfinder over their automatic drawings to pull out interesting compositions. A viewfinder allows students to evaluate a composition before drawing, taking some of the pressure off.

The above example used the song September Doves by Lost Dog Street Band.

Step 4: Re-draw the strongest composition several times.

As students repeat their drawings, have them identify imagery. Notate directly on each sketch the images that emerge. Relate this step to a scavenger hunt to give it a fun twist!

Step 5: Transfer the final composition to a surface and medium of your choice.

Provide a limited selection of surfaces and media to complete the final drawing. Use materials and techniques students have already learned in your class, or introduce something new!

If you want to push this project even further, tie it back to the Fillmore posters. Have students use their composition to design a poster. The poster should advertise a local show for their chosen music artist.

Automatic drawing techniques show reluctant students they can use their imagination without fear to find success. Sometimes the scariest part is anticipating failure or thinking the final artwork will look “weird.” By demonstrating automatism in front of your class, you can show students how to embrace the messy process of artmaking. You can also model how to make artistic decisions in the moment and take risks.

Learning that letting go is a part of the process takes the pressure off and helps students avoid overthinking. Instead, students can focus on creating. By incorporating student choice through music, you can gain a more personal connection with your students. You can even create a class playlist with student song suggestions to listen to during studio time!

How do you incorporate student interests in your art lessons?

What are some benefits you have found by infusing music in your art room or curriculum?

How might automatic drawing push your students past standard image tropes?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.