Evaluations. For some art teachers, the very word brings about feelings of worry, dread, or self-doubt. For others, evaluation discussions are met with a dismissive attitude and a comment that the evaluator “doesn’t know anything about art education.” These feelings are valid and unique to the individual art teacher and their context. However, there are several strategies we can use to gain constructive, actionable feedback from the evaluation process. This feedback can prompt your next professional steps. We all want to be the best art teachers we can be. It all starts with taking charge of your evaluation process.

Learn how to take charge of your evaluation with the following pointers:

Prepare yourself for an evaluation.

A critical part of almost all teacher evaluations is the observation. But this is only one aspect of a more extensive evaluation process. Terri Caton, an elementary principal in Ohio, suggests spending time with the evaluation tool. Highlight strengths and areas you identify that need growth. Circle descriptors that may be confusing and ask for clarification from a critical friend. Terri shares that “being knowledgeable of the evaluation tool is one step towards taking the lead of your evaluation. This will ensure the feedback you receive is meaningful. Consider, what does it look like for you, an art educator, to meet the goal statements?”

Check out eight steps to prepare for your next formal observation and the PRO Pack, Preparing for Evaluations and Observations for resources to rid you of the pre-conference jitters.

Prepare your administrator for an observation.

Take time to familiarize yourself with your district’s evaluation tool, and reflect on potential areas of growth. Then, schedule a meeting with your administrator before your observation if one was not pre-scheduled. Discuss the instructional practices you have been working on that warrant feedback. This will help focus the observation and subsequent feedback on actionable next steps based on the topic(s) most relevant to you. Terri Caton says, “an evaluation is about validation and growth.” The process should support what you are doing well and highlight areas for improvement.

Some instructional practices the evaluator will see simply by stepping into your classroom. Others may be more abstract. Kaitlyn Kennedy, a middle school art teacher, prepares her administrator by collecting and presenting evidence ahead of time. She shares, “An observation is only a small snapshot of what we do every day with our art students. Evaluators can only provide feedback on what they see in the classroom or from collected evidence.” This documentation can be found in lesson plans, student work, parent communication, and lists of engagement outside of the classroom. “This evidence not only helps my evaluator see a complete picture of who I am but also shows that I am dedicated and prepared,” says Kaitlyn.

Most evaluators do not know what it is like to be an art educator. Terri Caton admits that she is no visual art expert. During an observation with any teacher, she is looking for engagement, relationships, confidence, and the use of age-appropriate resources. She looks for modeling and questioning that prompt higher-order thinking. Take control and prepare your evaluator by sharing the art education-specific planning, pedagogical decisions, and the processes they will witness in the art room. You are the in-house expert on visual art. Constructively share your knowledge to support the process and provide clarity for all.

Consider who is doing the evaluation.

Sometimes, the relationships between an administrator and an art educator may be strained for various reasons. Or, perhaps the same administrator does your evaluation each year, and you want a fresh perspective. Research the possibility of requesting a different evaluator. If you are afraid that this will make a strained relationship even worse, phrase the request in terms of growth. Terri Caton shares, “A teacher may want to focus on an area of professionalism that warrants the outside perspective of a central office administrator. An observation from a curriculum director may serve as a strategic professional step forward.”

Many district administrators want to be back in classrooms, but their schedules are restrictive. Provide them with an opportunity to spend time with students and support their professional growth. And who knows—they may see something during the observation that they keep in mind for the future. They may reach out to you later for a potential professional possibility, a presentation, or committee membership.

Own your observation.

During an observation, remember that your evaluator is a human and can be interacted with. When students are working, prompt them to share their work with the new adult in the room. Point out things that you believe are going well that they may miss. This is yet another opportunity to take the lead and ensure that the resulting feedback is purposeful and actionable for your instructional needs.

Make it a two-way conversation.

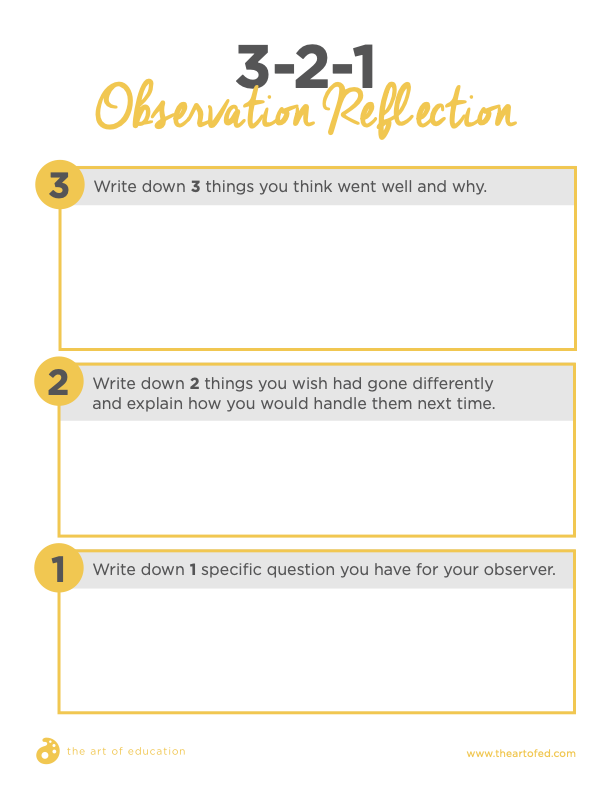

After most observations, there will be a scheduled post-conference meeting to review the evaluation. You may receive district-mandated questions to fill out prior to the meeting. The goal of these questions is to help you reflect on your teaching practices. If you need a template to help guide your post-observation reflection, download this 3-2-1 Observation Reflection and bring it to your meeting.

Download Now!

When it comes time for the meeting, do your best to put personal reactions to the side and listen. Kaitlyn Kennedy knows that these conversations may seem like a surprise at first, “The administrator may see something that you didn’t while you are stuck in your little bubble of the art room. But we all have room to improve our practice. That is if we are aware of what we need to improve upon.”

If you receive unexpected feedback and need space to process, here are a few ways you can respond:

- If you feel defensive, say, “I need to take some time to process your feedback. I will get back to you shortly.” Take the time you need, make notes, and schedule a follow-up for a two-way conversation.

- Restate what you hear as you seek to understand. “What I hear you saying is…”

- In an objective tone, ask for examples. “Can you give me an example of what that might look like in the art room?”

- Ask for clarity. “Can you share with me the part of the lesson where you noticed that?”

- Ask for additional feedback. “Do you have any suggestions on how I can improve in my identified areas of growth?”

If you feel that certain pieces of feedback are unwarranted, collect evidence to supplement the next conversation. You may have evidence of communication, projects, or school involvement of which your evaluator is unaware. It is helpful to provide the documents to keep the feedback as relevant as possible.

Is your evaluation outstanding and near-perfect? Great! It is nice to receive lots of validation, but discussing areas for growth pushes us to keep learning and challenging ourselves. It may seem counterintuitive, but ask for growth feedback if it is not provided.

Consider the feedback and put it to work.

Think about how you would want your students to receive and consider constructive feedback on their work. You can model how to take and apply feedback through this process. Go over your evaluation with a critical art teacher friend. Your inclination may be to complain about the process or the administrator. Instead, focus on how the feedback can impact your pedagogy. Discuss potential changes you can make in classroom management or assessment protocols. Take time to plan for questions to ask students. Discussing these topics with a fellow art educator can help both of you see possibilities for growth in your own classrooms.

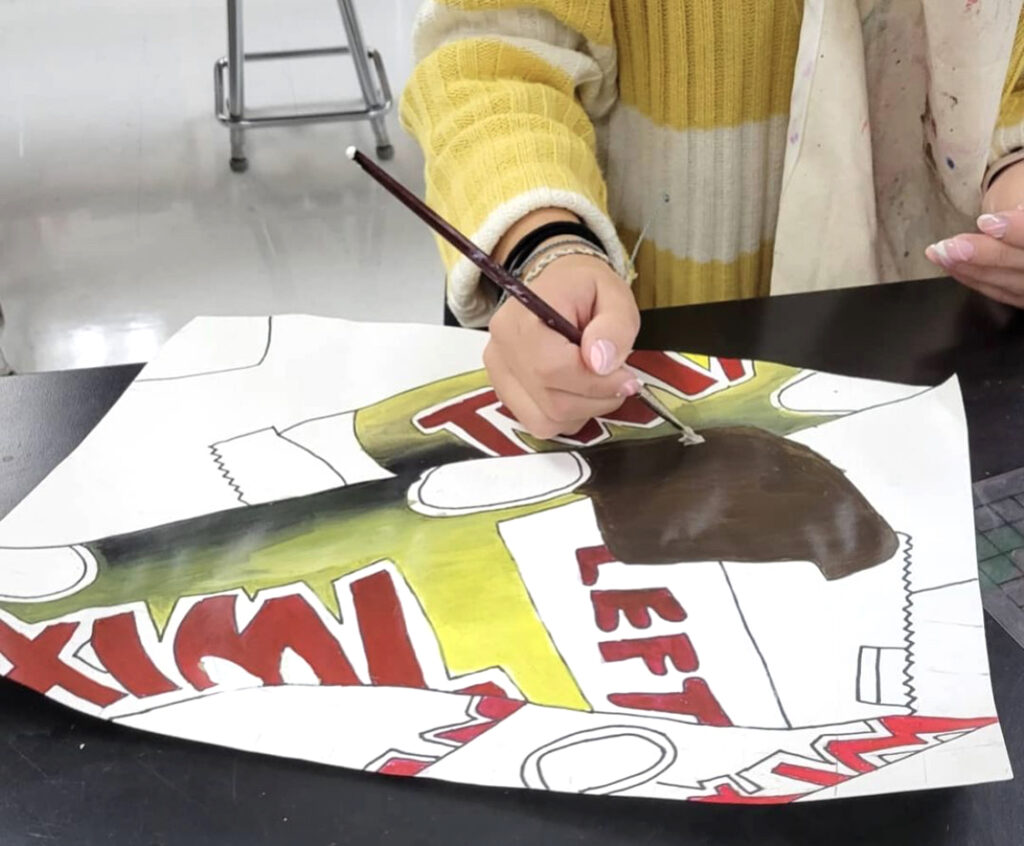

Administrators, like teachers, are busy. However, personally invite them into the art room when it isn’t evaluation time. Share an exciting project that students are engaging with or unexpectedly delightful outcomes they need to see. Ask them to come back and provide additional feedback on the modifications you have made based on the evaluation process. Kaitlyn Kennedy reflects, “I often think, as art educators, we feel overlooked and undervalued. Having an administrator stop in to see what we and our students are doing will help them see how important our work is and help us to feel valued.”

Evaluations are a part of our work as art teachers. They can be an experience to dread or dismiss as unnecessary. However, when we take charge of the process and support evaluators, we can show them the inspiring engagement in our art rooms. The feedback you receive can validate your work and make you a stronger art teacher. Whether or not you have an evaluation coming up, we hope you use some of these pointers to be a leader and take charge of your professional growth.

How do you want your students to receive and apply feedback? How do you model this in your own practice?

When was the last time you invited an administrator into your art room and were open to their suggestions?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.