Note: Be sure to review all resources and preview all artists before determining if they are appropriate to share with your students.

Eerie art has had its place in the creative world for some time. It has been used as a platform to question the spiritual realm, human mortality, death, and more. By analyzing artworks from art history, students can increase their intellect, personal, and social development. Last year, we took a look at five artworks that displayed a bit of the macabre and a lot of underlying tragedy. This year, let’s go around the globe with five Non-Western artworks, steeped in culture and tradition!

Here are five intriguing Non-Western artists and their artworks you do not want to miss!

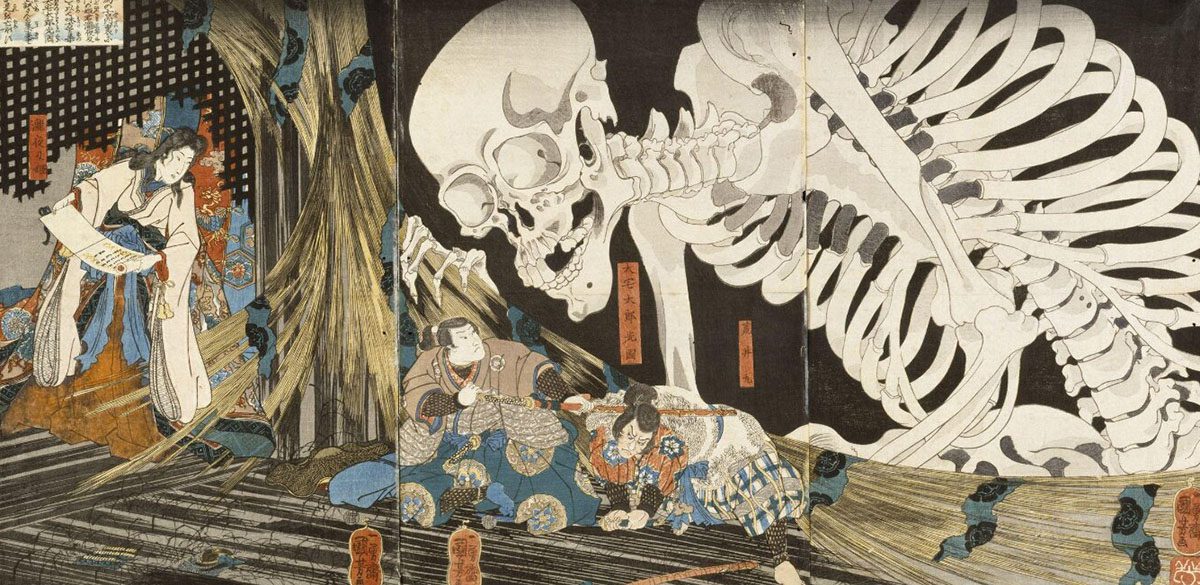

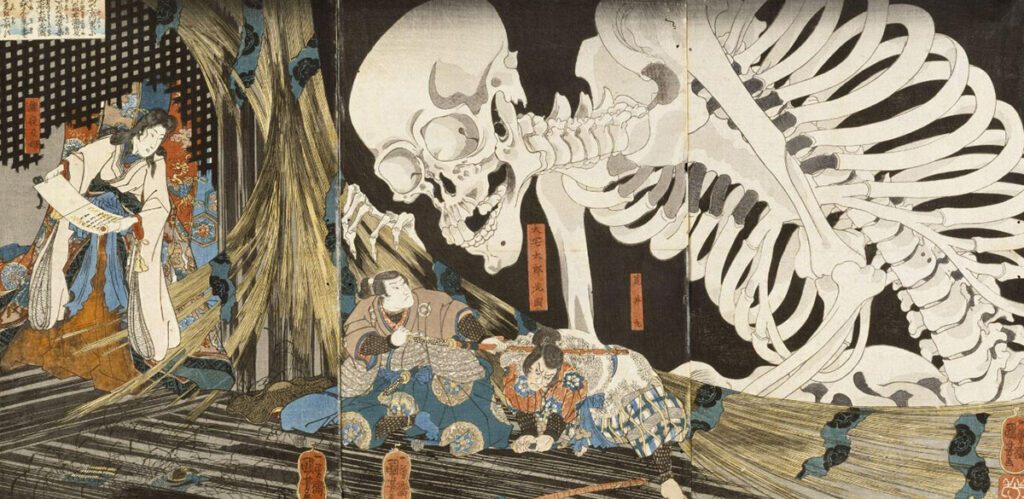

1. Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Kuniyoshi was a great Japanese artist known as a master of the ukiyo-e genre. Ukiyo-e featured a range of subjects, including landscapes, flora, fauna, and folktales. Kuniyoshi focused a lot of his attention on the latter subject, which ranged from mythical creatures, ghosts, demons, samurai warriors, and even sumo wrestlers. His main method of working was woodblock printing, much like the modern-day linocut.

One of his most regarded works is Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Specter, a triptych showing a giant skeleton summoned by a witch named Princess Takiyasha. The Princess is the daughter of Taira Masakado, a warlord who met his demise during a failed rebellion in Kyoto. She commands the skeletal being to protect her from a henchman sent to kill her. The work catches the viewer in a dramatic pause between the Princess’s guard and the henchman, with the skeleton lurking in the background. The skeleton commands the composition with its white bones contrasting the dark void behind it.

2. Nkisi N’Kondi Figures

Nkisi figures are wood carvings and hold many sacred beliefs to the Congo people. Also known as power figures, nkisi loosely translates to the word “spirit.” These spirit or power figures hold a sacred medicine activated by a supernatural force in the physical world. The result of this transaction is believed to cure a physical ailment, illness, or even social dispute.

In order for this transaction to occur, the figure and a spiritual guide must take an oath. The parties involved will drive a nail, spike, or peg into the nkisi figure. If the bond is not honored or wrongdoing occurs, the spiritual guide has the ability to invoke the nkisi spirit to seek vengeance on the wrongdoer(s). The more nails or pegs a figure has, the longer it has been in use and the more transactions it has taken part in.

3. Tlingit Mortuary Poles

The Tlingit are indigenous people from the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America, traditionally encompassing Alaska. Like many Northwest Coast Native Americans, the Tlingit made totem poles. A totem pole uses symbols to represent a significant event, person, or story in a tribe’s history. Poles typically stayed in their original location, unless they posed a danger to the tribe. Eventually, the pole would deteriorate and find its place back in the earth, bringing the beginning and end of the wood’s journey full circle.

Mortuary poles were specifically used to house the remains of someone significant within a clan. Tribe members hollowed out the back of the pole, placed the person’s remains in a box, and housed the box in the cavity. This burying method differs from a memorial pole which is lifted to honor a member without including any remains.

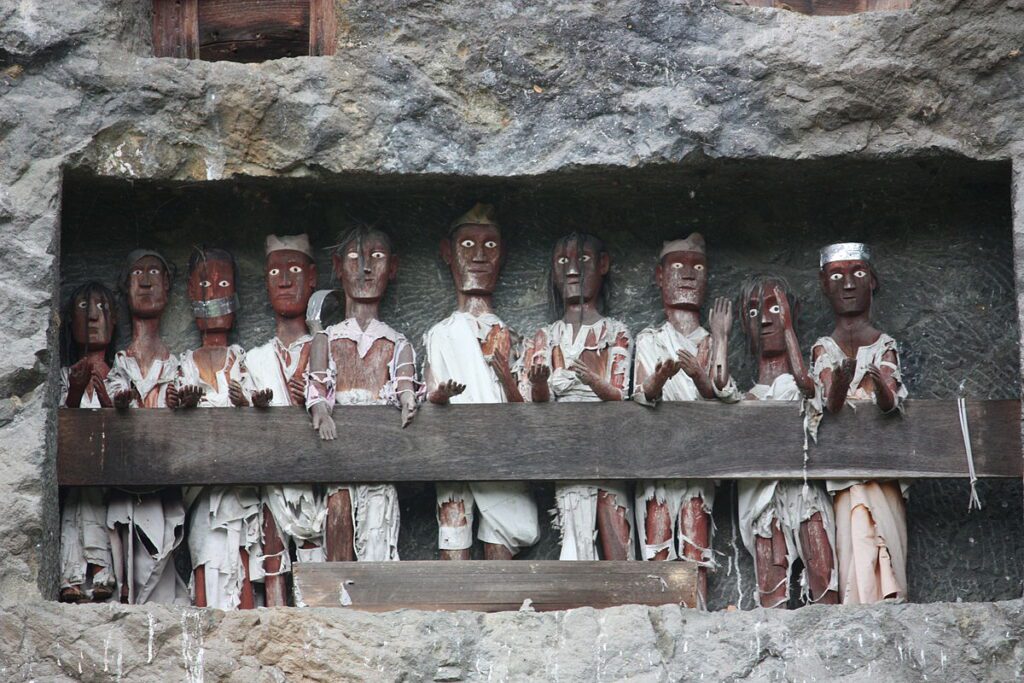

4. Toraja Grave Effigies

The Toraja people of Indonesia have a strong connection to their deceased relatives. An artist honors the deceased with a replica placed at the grave site called a tau-tau. “The line between life and death is not black and white” so they often continue to visit the tau-tau, make sure they have their possessions, and bring them daily meals.

Torajan funerals are a huge event! They can last up to a week and involve the slaughtering of animals, exchanges of money, and gifts. These funerals are very expensive so many families save for years, making death central to the economy. After the festivities, the tau-tau gets placed in a sacred or special location, such as a cliffside, cave, or hill to take watch in the land they loved. A child who passes away in the Torajan culture is placed inside a tree trunk so they can continue to grow as the tree grows. Instead of mourning the loss of a loved one, the Torajan people can live with their loved ones in their earthly life.

5. Asmat Ancestral Skulls

The Asmat people from Papua, New Guinea live a complex lifestyle closely associated with death and spirituality. They create rare works of art such as carvings and masks. But of their works of art, the most peculiar may be the ancestral skulls.

Headhunting and cannibalism were a part of the Asmat culture until as recently as the 1970s. They believe the skull is associated with the growth and containment of someone’s spirit. Many believed you could become the deceased person if you consumed their flesh.

However, these ancestral skulls were used ornamentally, which is why they are heavily decorated with beads, seeds, feathers, and shells. When a loved one would pass away, they would honor them as an ornamental skull and plug the nose and eyes so evil spirits cannot enter. The Asmat sometimes sleep with the ancestral skulls for protection against the physical and spiritual world.

Artworks are always more than they seem on the surface. Take the time to closely examine the artworks above and discover the rich history and tradition from which they stem. Each work is deeply infused with symbolism, ritual, tradition, or even catharsis. A contextual point of view helps tremendously when viewing these or any work of art. What originally appeared as eerie, may become beautiful artifacts that entwine visual art and anthropology. We hope you learn something new (and maybe teach your students too!) with these five intriguing artworks.

What artworks would you compare and contrast with these?

Are there other Non-Western artworks you would add to this list?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.