History and art are deeply intertwined. Art tells rich stories about people, places, cultures, and traditions through imagery, symbolism, and processes. Did you also know military history shaped many well-known artists? The creative minds of courageous artists inspired others, shaped opinions, and saved many lives. Harness this connection in your art room to encourage problem-solving, discuss fascinating art careers, and prompt strategic messaging through imagery.

Hear the stories of artists in the military, plus ideas to bring them to your students.

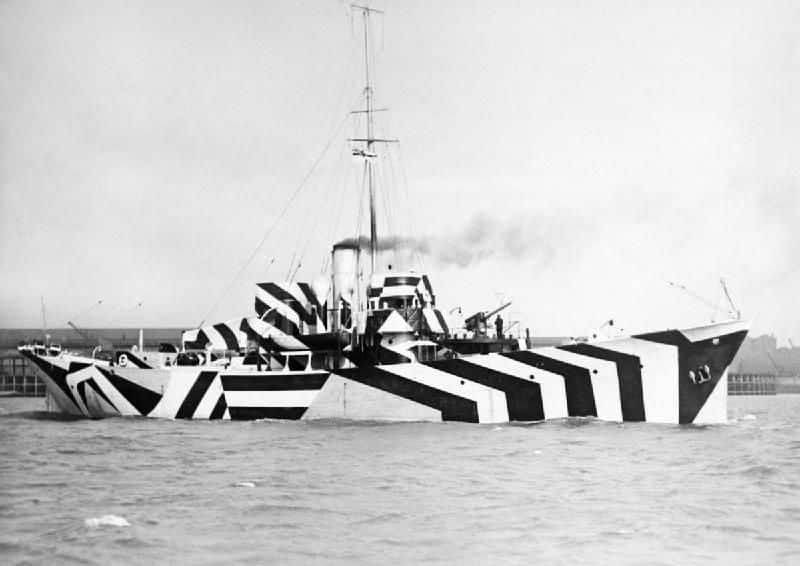

A little razzle-dazzle may have saved lives in World War I.

In the days before radar, soldiers would need to spot an enemy ship through a scope and estimate its distance, direction, and speed. In 1917, as German U-boats targeted ships with deadly accuracy, artist Norman Wilkinson came up with a radical plan. Rather than trying to hide the ships, he wanted to paint flashy designs to disorient the enemy. The Navy experimented with painting ships using geometric lines and shapes to make it harder to tell the ship’s orientation.

Put this story to work in your classroom.

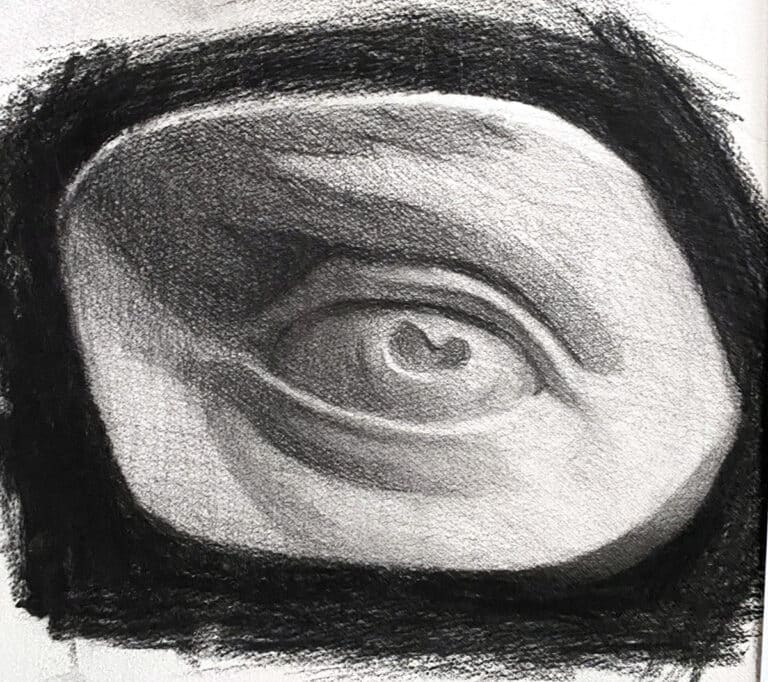

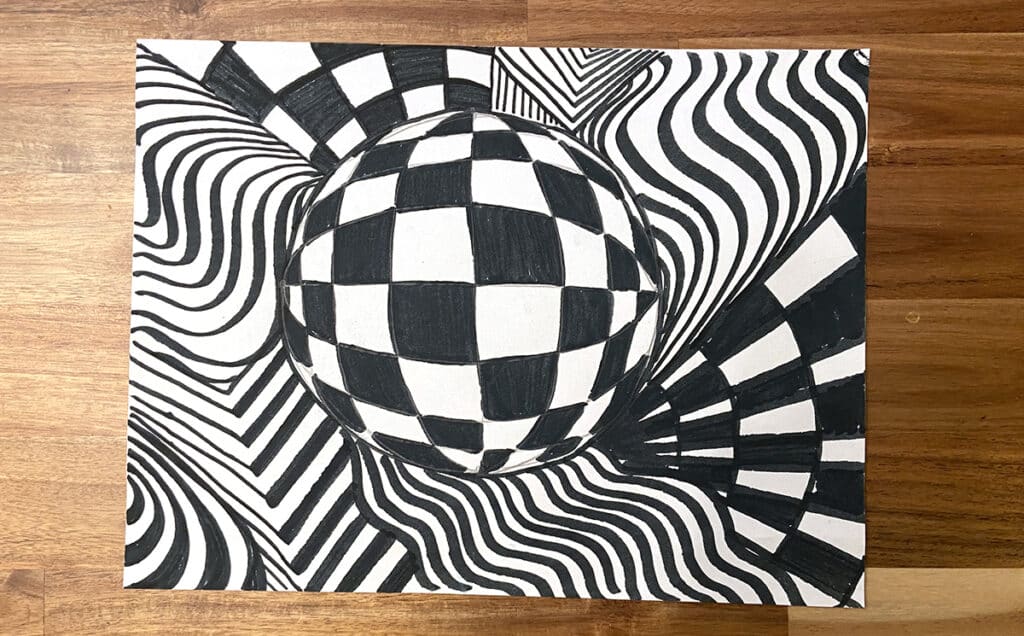

Many art teachers love Op Art because it’s systematic and highlights the careful arrangement of the elements within a composition. Many students love Op Art because the projects have a high success rate. It’s easy to understand and it’s visually striking.

Share the history of Dazzle Camouflage as a hook to get students interested in your Op Art lesson. If you want more ways to introduce Op Art, check out the artist bios of Victor Vasarely and Bridget Riley in FLEX Curriculum. You’ll also find student-facing resources like timelines, videos, and visual references of Op Art patterns.

Who you gonna call? Ghost Army!

During World War II, the U.S. Army recruited artists for what they described as a non-combat camouflage unit to misdirect the enemy. The job was far more risky than it sounds. The 23rd Headquarters Special Troops was eventually renamed the Ghost Army. Artists, including some who would go on to have prominent art careers, such as Ellsworth Kelly and Art Kane, utilized their talents. They created an illusion that the Allied forces were preparing to go to one place while they actually planned to go to another. To make this illusion, they constructed inflatable tanks, stretched canvas over wooden mock-ups of trucks or planes, and used audio recordings to simulate the din of an active platoon.

One strategy was partially covering and camouflaging their creations so enemy scouts would catch their “mistakes.” Because the scouts believed they caught a glimpse of something they weren’t meant to see, they perceived it as valuable intelligence. For a group of roughly 1,000 artists, impersonating a group 40 times their size was extremely dangerous. Success in their mission would draw the enemy closer to them. However, they couldn’t defend themselves in heavy combat. Their creative and courageous actions were successful and likely saved the lives of tens of thousands of soldiers.

Put this story to work in your classroom.

Design immersive installation pieces that incorporate sound, light, and tactile elements. If you don’t have the space, time, or resources to do full-blown installations for each student, groups can mock up faux installations by drawing on printed pictures of school spaces. Students will consider how the elements they include can misdirect their audience and create intriguing stories with twists and turns. This exercise encourages students to consider the role of art in shaping perception and influencing reality.

Soldiers win the fight, but artists win hearts and minds.

Wars are fought on multiple fronts. In order to be victorious, the nation must support soldiers on the battlefield and at home. To win hearts and minds, they produce propaganda. In January of 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt gave an address making the case for aiding Great Britain and greater US involvement in World War II. He said the US would be helping to protect four universal freedoms that all people deserve: speech, worship, want, and fear.

Norman Rockwell listened to the speech and it inspired him to create his Four Freedoms series. He went to the Office of War Information with his posters and they turned him away. The Saturday Evening Post believed in Rockwell’s vision, and they commissioned him to make the works to go along with corresponding essays. People loved the series! The Post received 25,000 requests for reprints. They quickly worked out a deal to sell war bonds and stamps featuring Rockwell’s images. The Office of War Information came to print roughly 4 million posters of Rockwell’s Four Freedoms between 1943 and 1945.

Put this story to work in your classroom.

Use Norman Rockwell to introduce media literacy and visual communication. Discuss the series and how he made abstract concepts concrete and relatable for an audience. Challenge students to make visual representations of ideals they hold dear. Hang them around the school to encourage character development. It’s a great way for students of any age to be a force for positive change!

Inspire students to look at the benefits and importance of visual art outside of your classroom walls and their current experiences with the military stories above. The brave and ingenious artists of the Dazzle Camouflage, Ghost Army, and Norman Rockwell all impacted society and history for the better with their creative problem solving. Bring these artists into your curriculum to foster historical connections, honor their contributions, and build communication skills.

What is your favorite fun fact about art shaping history?

Do you do anything special to celebrate Veteran’s Day in the art room?

To continue the conversation, join us in The Art of Ed Community!

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.