Every year, it seems like the student behaviors get more challenging. Strategies that once worked are no longer effective and you may feel like you’re at the end of your rope! There’s good news—now is the perfect time to reset student behaviors in the art room. Curb wild behaviors with the seven strategies below.

First, take a look at common student behavior challenges by grade level.

Understanding common behavioral struggles by level can remind you of what’s “normal” and within your control. Younger elementary students (K-2) often struggle with impulsivity. They may grab supplies without asking, have difficulty waiting their turn, or become easily frustrated and cry or yell. As students move into upper elementary (3-5), these struggles can manifest as more deliberate acts like refusing to participate, arguing with peers, or becoming defiant when redirected.

In middle school (6-8), students grappling with self-regulation may exhibit withdrawal, disengagement, or even resort to more disruptive behaviors to mask their discomfort. By high school (9-12), these challenges may appear as increased anxiety, perfectionism that hinders progress, or shutting down when faced with perceived failure. Art teachers play a crucial role in recognizing these signs and responding with appropriate support and strategies.

Here are seven ways to handle difficult student behaviors in the art room.

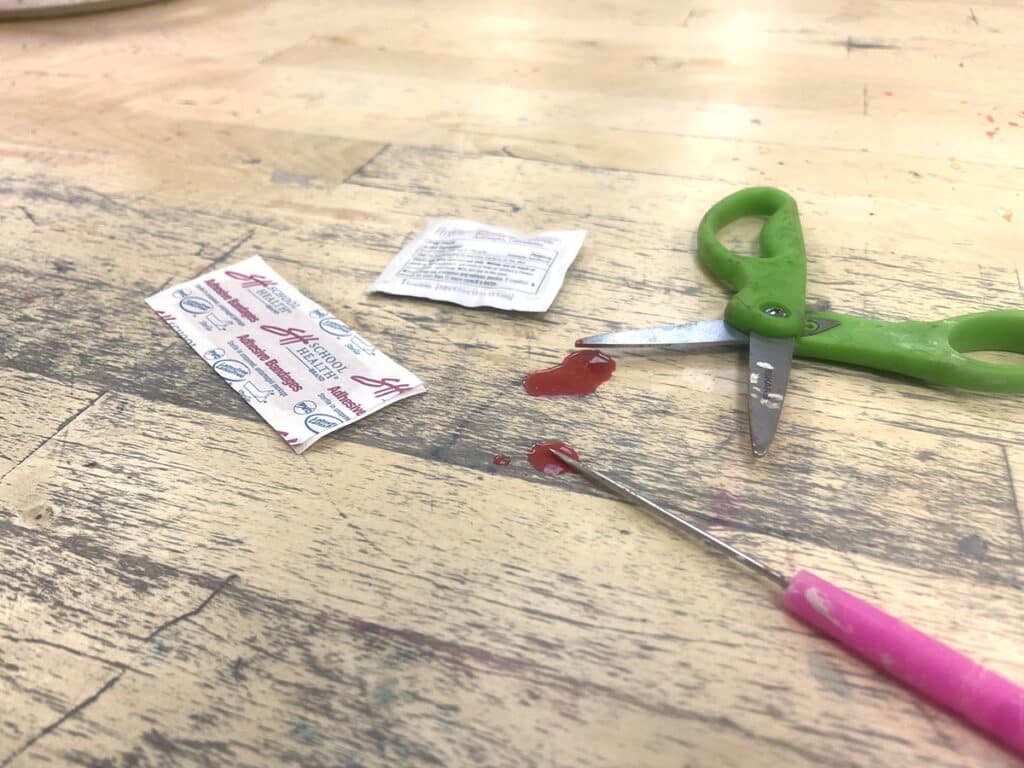

1. Prioritize safety.

You cannot address every behavior of every student all at once. Sometimes, words or actions are best to ignore. Other times, you or your students may need a break to cool off before addressing a problem. However, when it comes to safety concerns, it is important to always address these immediately.

For instance, if a student is waving a hot glue gun in the air while they’re fooling around, the first step is to get them to put the hot glue gun down on the table before someone gets burned. Discussing why they’re fooling around and any consequences they’ll be responsible for can happen later in the class period in a one-on-one conversation.

2. Consider environmental concerns.

While you can’t control every aspect of a student’s life, you can shape their experience when they’re in your art room. Let’s say your classes consistently come in loud and boisterous and it takes a large chunk of the period to quiet down. Take time to reflect and ask yourself what you can do to remove as many distractions as possible. Perhaps your classroom walls are full of color—artworks, anchor charts, and piles of collected boxes to upcycle. Spending one planning period to declutter and visually streamline your space may help students adjust more quickly when they walk through your doors.

Students are people just like you and have lots of things happening in their lives outside of your art room and school. For students walking into your classroom with the weight of the world on their shoulders or if they’re unused to art room chaos, designate a “calm corner” to unwind and reset.

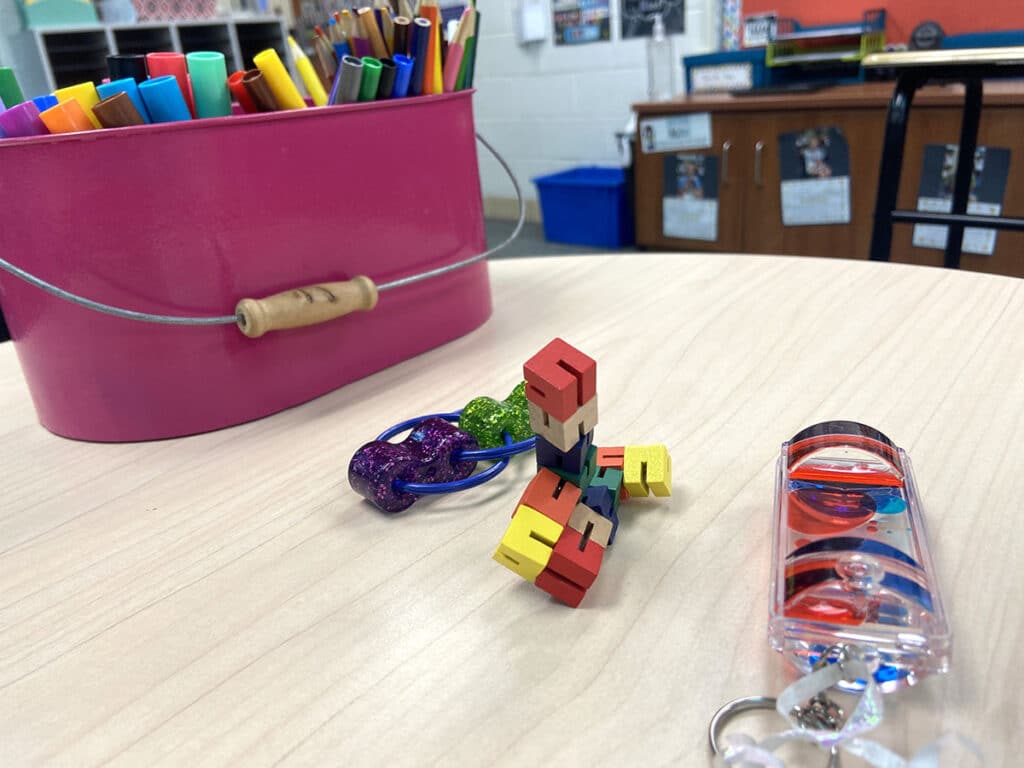

Other ways to help students who feel overwhelmed are to offer fidget toys or sensory items and alternative seating arrangements. Have these readily available so you’re not caught off guard in the heat of the moment. Proactive and early intervention will provide tremendous results!

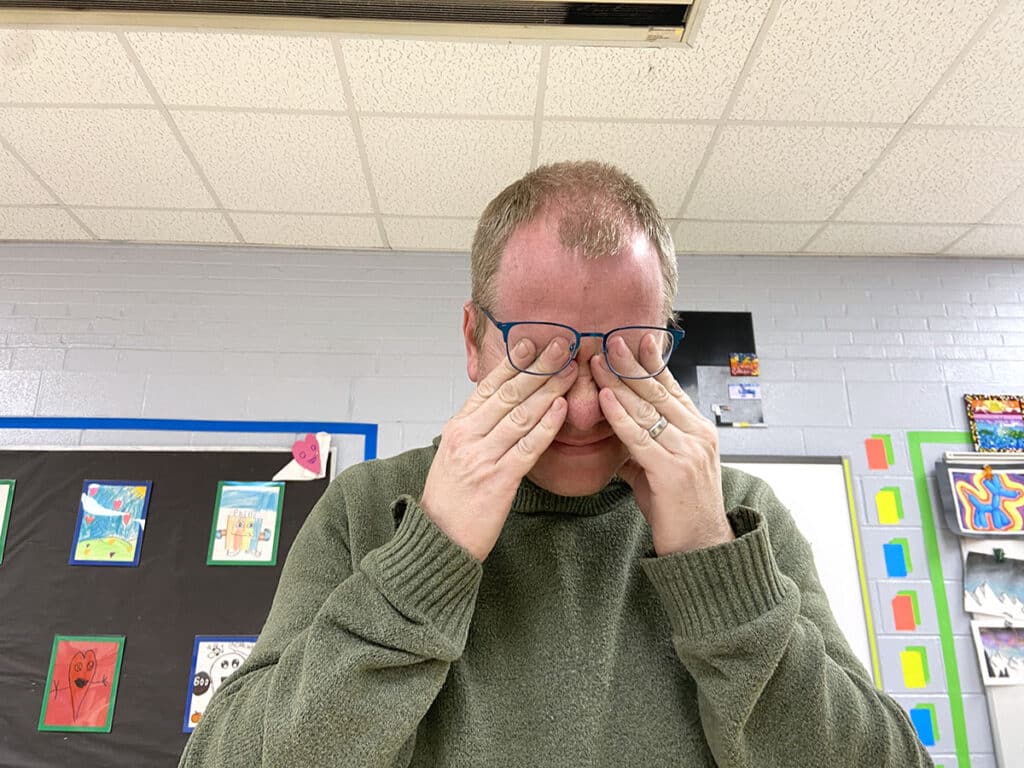

3. Share your calm when students bring chaos.

Using a calm voice goes a long way to de-escalate any situation. No matter what their struggle is, every student wants you to see, hear, and respect them. Aside from hearing the student out, ask them about their priorities and how they want you to help. In our haste to get things accomplished or consider the needs of the overall class, we can overlook individual needs that are easy to meet!

Sometimes we also revert to telling students what to do. Instead of dictating a solution, ask them to come up with one or provide two appropriate choices for them to select from. This allows students to actively participate in managing their emotions and behaviors and fosters a sense of agency and responsibility. For example, you can ask them, “Would you like to take a break in the calm corner or try a different early finisher activity?”

4. Address the situation immediately; you can always resolve it later.

When emotions run high, it’s hard to process or think rationally. Providing a short break before talking things out can be the best strategy. Once things are calm, re-engage students in a private conversation. Use this opportunity to discuss the situation, explore triggers and solutions, and reinforce expectations for appropriate classroom behavior. It’s okay to postpone the chat, but always remember to come back to it in a timely fashion so it keeps its potency.

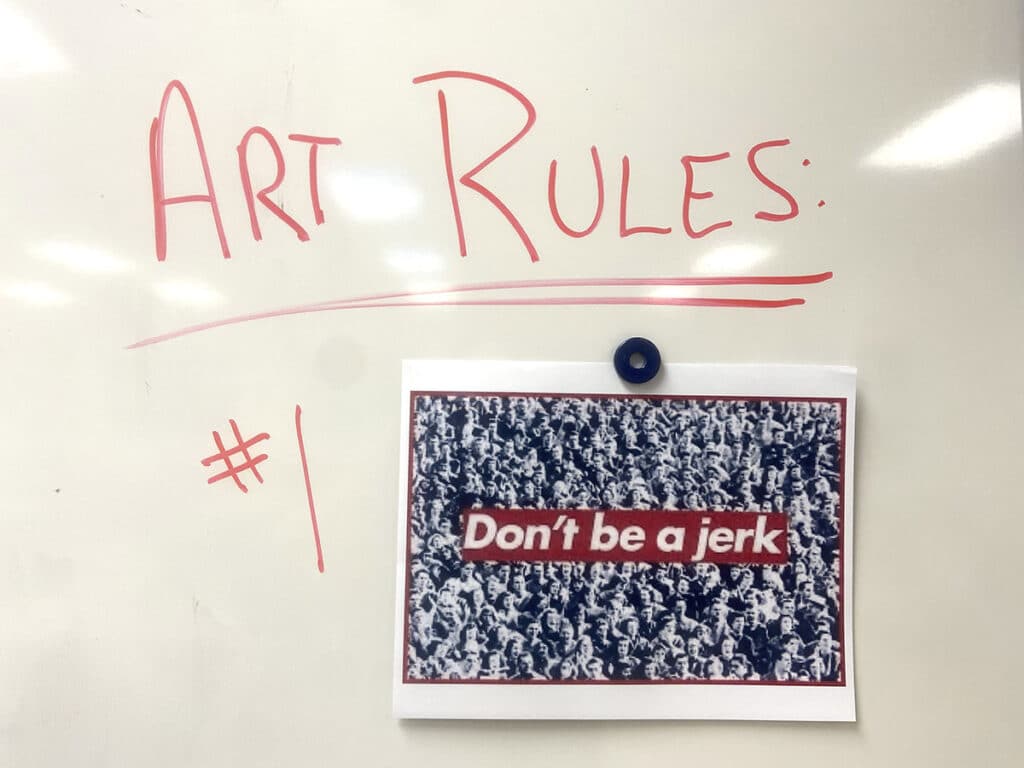

5. Keep your behavior system simple and predictable.

Make sure students know the consequences of their actions ahead of time—and then allow them to experience those consequences! Make sure that your communication centers around the action (versus the character of the student) and that the consequence appropriately correlates to the behavior. This simple shift in language can make a huge difference!

Let’s say you are using acrylic paint in a foundations class. As part of your instruction, you review how much paint should be on the paintbrush bristles and reiterate the importance of cleaning brushes well before the paint dries. You inform them that using acrylic paint is a special privilege; students must follow directions and take care of their materials or they will rectify any damaged or dirty items.

You notice a student smashed their brush into a glob of acrylic paint, jammed paint into the ferrule, and then left the brush on the table to dry while they chatted with a friend. You may say to the student, “Remember, it’s important to take care of our brushes so we can continue to use acrylic paint. Would you rather clean up five minutes early so you can thoroughly clean out the brush with a special cleaner or come back during your lunch and do it?”

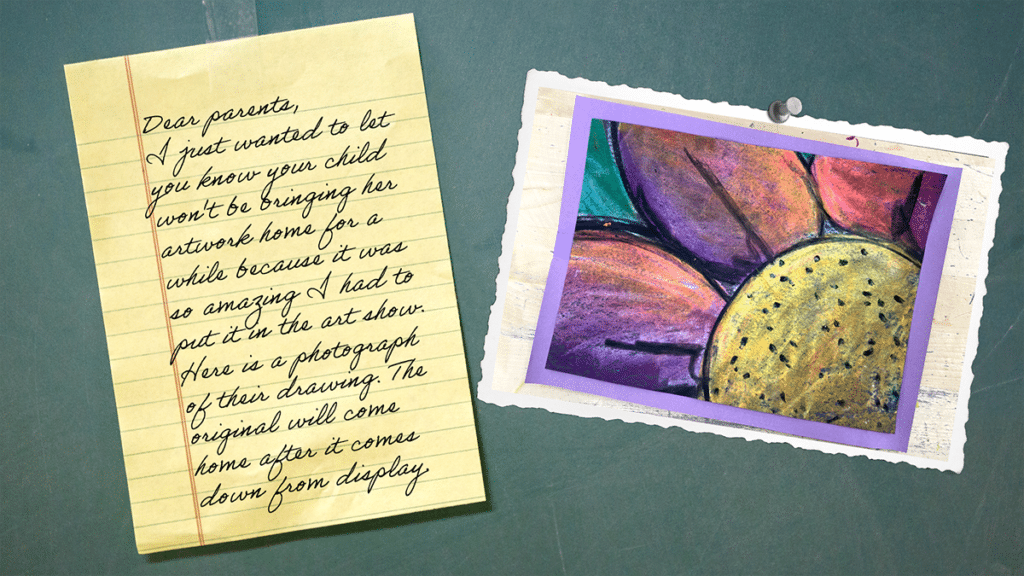

6. Build positive relationships.

The most powerful way to proactively manage your classroom is to get to know the students as individuals through their goals, interests, and lingo. When students like you and know you authentically care about them, they are more willing to cooperate, even if they don’t want to! Other ways to build rapport are to offer positive reinforcement and send good news home. Building strong relationships extends to parents and guardians as well, so invite them to partner with you through lots of positive interactions.

7. Ask for help!

Even in the best circumstances, teaching is a challenging job. Remember that you are also a lifelong learner. It is okay to ask colleagues for support. If you don’t feel comfortable reaching out to teachers in your building, share your struggles with The Art of Ed Community. Post a problem you are facing and art teachers just like you from around the world will share their empathy, encouragement, and tried-and-true solutions. If you want to learn more privately, watch PRO Learning for in-depth, self-paced videos on managing behaviors, motivating reluctant learners, de-escalation strategies, and more.

Here are two frequently asked questions when it comes to challenging student behaviors in the art room.

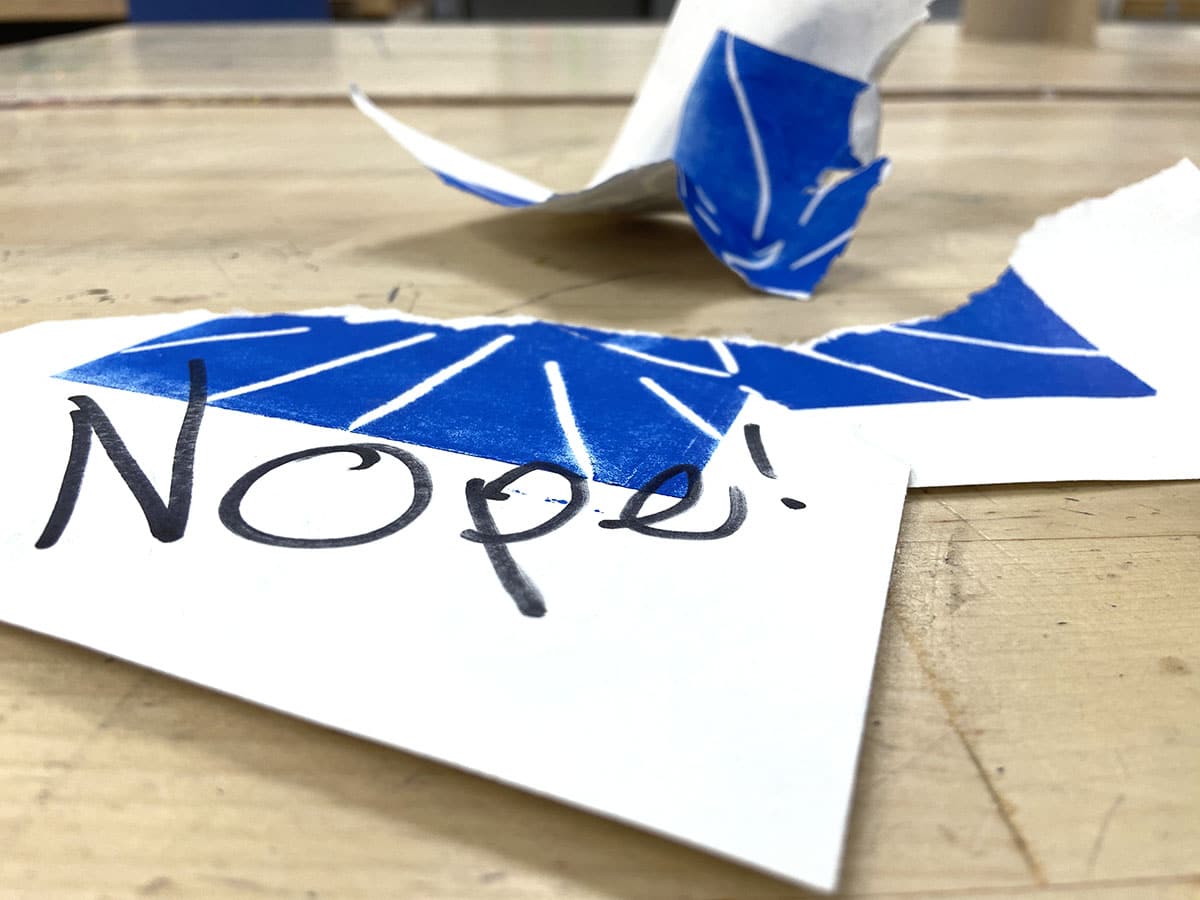

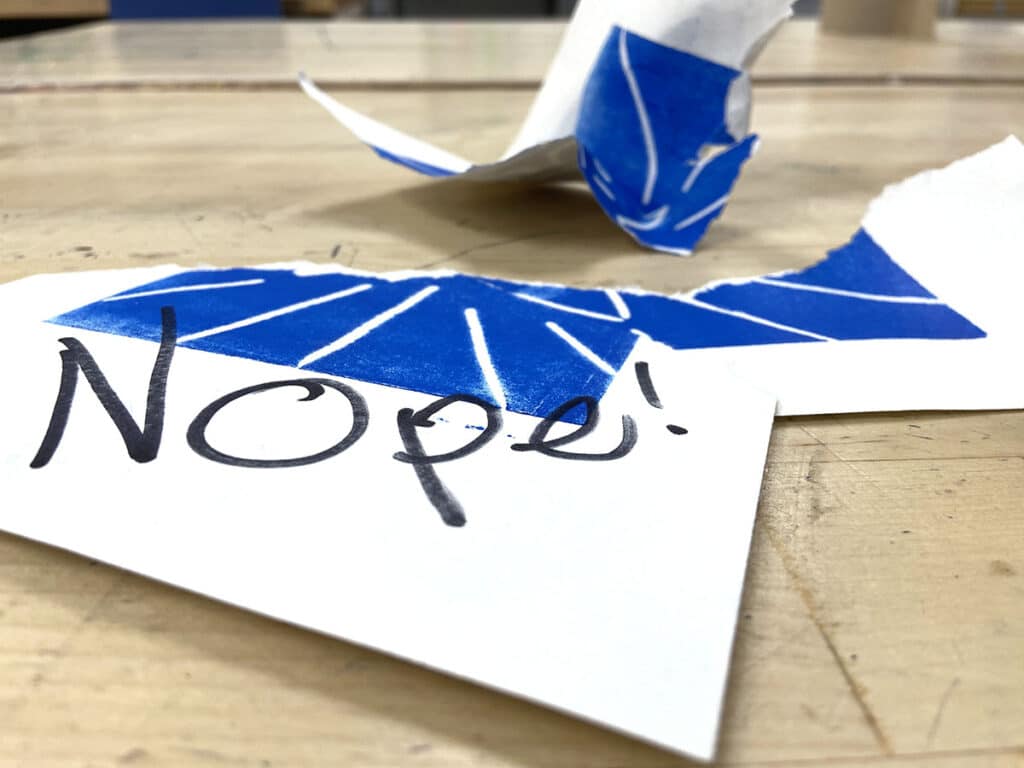

How should I respond when students say they hate my assignment or refuse to do work?

Start by acknowledging their feelings—not every assignment will be fun and it’s okay to feel frustrated. Shift focus to find something good in the project the student can connect with. Ask for specific things they don’t like about the project; thank them for their feedback and say you’ll keep it in mind for the next project and future students. Often, students want you to hear them and then they’ll move on!

It can also be helpful to be blunt, especially when they’re older. Explain, “Everyone has requirements at their job. As an art teacher, I am required to make sure every student learns XYZ skills. Your grade is based on your work that demonstrates these required skills. Let’s find a way to practice these skills in a way we both can be happy with.” You can also tie their assignment to their final grade which may impact graduation requirements, college acceptance, and GPA.

How should I respond when a student uses foul or insulting language at me?

While it is natural to mirror another person’s tone, as the authority figure and role model, you must keep your cool. Taking the bait and reacting with anger rewards the student by letting them control the situation and emotions. You can quickly and coolly dismiss the insult while still verbalizing that you don’t condone the behavior. Say something like, “I’m sorry you’re having a hard time right now. It is natural to feel upset when you’re struggling, but in this classroom, we treat everyone with respect. I’ll be happy to help you when you are up for it.” Then, move on and focus your attention on the students who are meeting expectations.

Behavioral challenges evolve alongside students’ developmental stages, from the impulsivity of young children to the more complex struggles of adolescents. At all ages, prioritize safety while understanding that every issue requires a timely resolution, but it doesn’t have to be immediate. Prevent problems by minimizing sensory overload, offering calming spaces, setting clear expectations, and building positive relationships with students. When problematic behaviors do arise, stay even-tempered, acknowledge feelings, and empower with choices. With these strategies, navigate challenging behaviors and create a thriving art room where everyone feels respected and valued.

How do you build a respectful community in your classroom?

What de-escalation strategies work in your art room?

To continue the conversation, join us in The Art of Ed Community!

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.