Have you ever glanced at a rubric and had your eyes glaze over and your mind tune out? Rubrics can be great tools for teaching and learning when they’re used in the right way. Misuse them, however, and they quickly become objects of confusion and boredom.

A strong rubric captures the heart of a lesson or unit – what you want students to know and be able to do – and states it in accessible language. A rubric should read like a road map, showing the learner where they are and where they need to be for mastery.

All rubrics should meet the following criteria.

1. The rubric should be standards-based.

Design rubrics to assess the state or national standards to which you teach. Unless stated in the language of the standard, do not include things like behavior or workmanship. Write rubrics to reflect what your students know and what they are able to do. Rubrics are not for enforcing your rules about labeling work or getting to class on time.

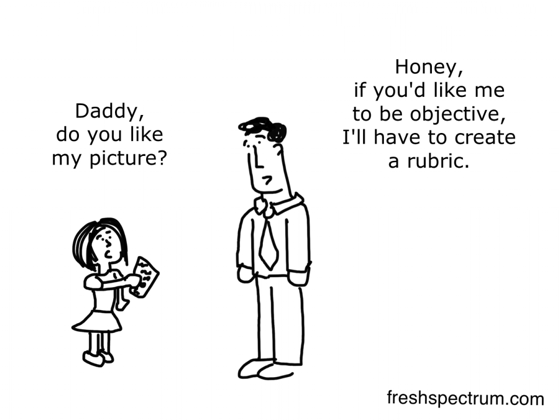

2. The rubric should be objective.

A good rubric objectively lays out specific things you are assessing. Make your descriptions of each level clear and nonjudgmental. Avoid using subjective phrases like “excellent use of color” or “poor composition.” Instead, describe what the work looks like. You might say, “color is solid and fills the space,” or, “composition lacks variety in size.”

Rubrics should communicate where students stand in relation to mastering specific information. Including sad faces or words like “failed” can make students feel disheartened. Using objective language will help students see where they are compared to the end goal.

3. The rubric should be direct.

Quality rubrics get right to the point of the learning goal. Keep your rubric clear and direct. The point is to communicate information about the learning process to the student. That can get lost if you try and include too much. A good rule of thumb is to base rubrics on one learning goal with no more than three categories of description. It’s also important to avoid assessing things that are beyond the scope of the standard. For example, if you’re teaching about applying methods to overcome creative blocks (VA:Cr1.1.7a, 7th grade) does assessing time on task apply to the achievement of the goal? If your answer is no, leave it off your rubric.

Create a Rubric in 4 Easy Steps

1. Start with a standard.

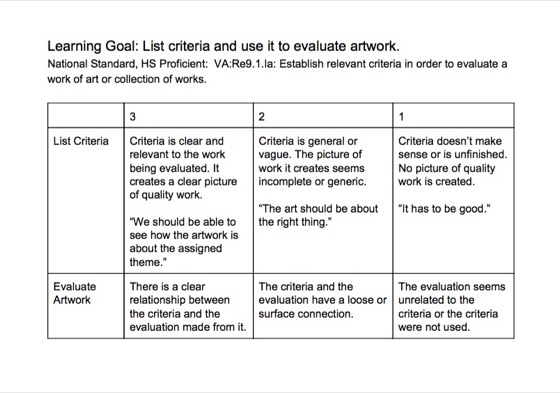

For example, HS Proficient, VA:Re9.1.Ia: Establish relevant criteria in order to evaluate a work of art or collection of works.

2. Re-write the standard using student-friendly language.

For high school students, you may not need to change much. Always think about the age of your students. In broad terms, think about what students will need to do to meet the standard. Doing so can help you decide how to share it with students. Using the example from number one, you might say, “List criteria used for evaluating artwork.”

3. Think about what different levels of success would look like.

List criteria and use it to evaluate artwork. Organize this criteria by number or letter. You can also assign point values at this stage. In the example below, a number 3 represents a student achieving the standard. If you’d like to keep this example, click the image to download it!

4. Use it.

The learning goal should now be the starting point for your instruction. Share it with students at the start of the lesson or unit.

The Takeaway

Quality rubrics start with defined learning goals that communicate educational targets in student-friendly language. They should be standards-based, objective, and direct. Good rubrics are powerful tools that help students understand what they are expected to know and be able to do. Plus, they provide a way for teachers to focus their instruction.

{image source}

What is the trickiest part of writing a rubric for you?

Do you have tips for converting standards into student-friendly language?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.