As an illustrator, designer, and artist, I strongly believe combining the written word with images to tell a story is one of the most powerful ways to communicate. It is how children begin developing storytelling and narrative skills from an early age. But as they grow older, the emphasis is shifted into other academic areas. Rather than embracing the unique ways the medium can communicate and provide access to different kinds of learners, the combination of the visual and written word tend to be looked down upon and considered “low art.” (Comics are for kids!) Zines are an opportunity to (re)introduce students to this methodology and give them a chance to take on the role of learner and maker.

So, what is a zine and why should I teach them?

Zines, Defined

Let’s take a look at a few definitions to better understand what a zine is.

According to Merriam-Webster, a zine is:

a noncommercial often homemade or online publication usually devoted to specialized and often unconventional subject matter.

A more expanded definition can be found over at Wikipedia:

A zine (short for magazine or fanzine) is most commonly a small circulation, self-published work of original or appropriated texts and images usually reproduced via photocopier. Usually, zines are the product of a single person or of a very small group. Zines first emerged in the United States, where the photocopier was invented, and have always been more numerous there.

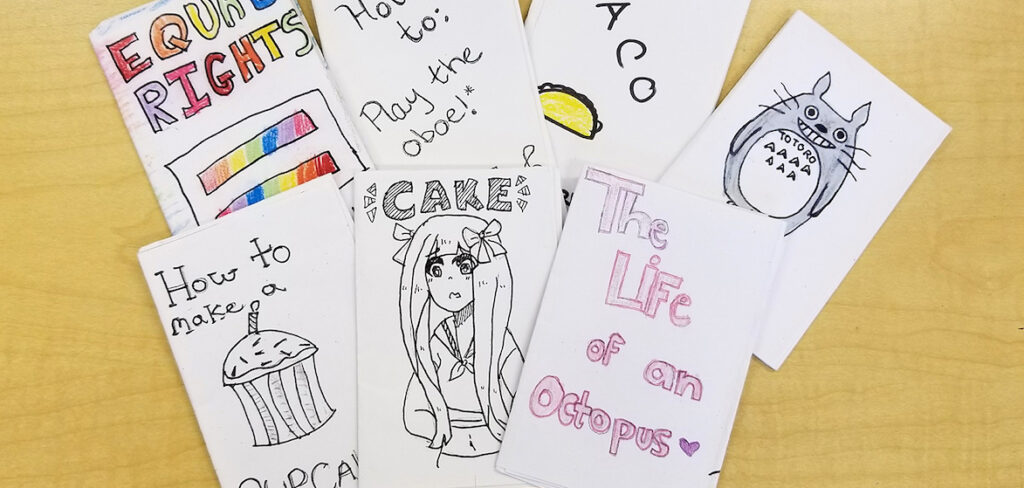

I see zines as an opportunity for students to serve at the intersection of maker, expert, and teacher. Students can tell stories and share their knowledge through both images and text and share this learning in a low-cost, easy to reproduce fashion.

The Benefits of Zines

The informality and ease of reproduction have always been key factors for me when thinking about reasons to teach zines. They can take many forms and be as complex or simple as students choose to make them. They can also include little to no writing and be comprised almost entirely of drawings or images. Students don’t need to be accomplished artists to do this, as they can fill their books with borrowed imagery and collages to help tell their story.

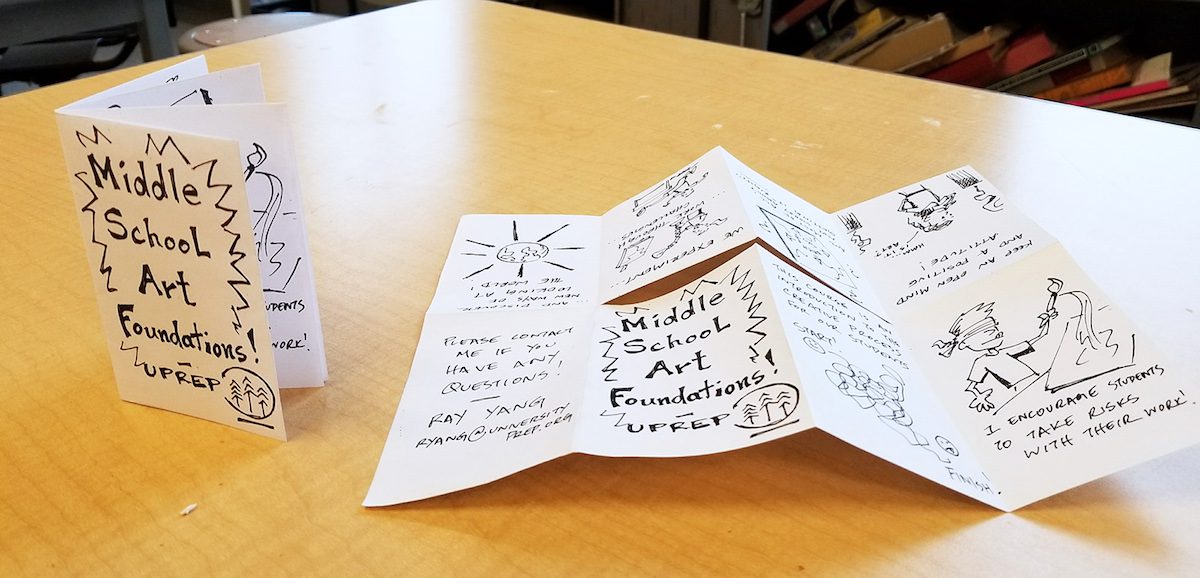

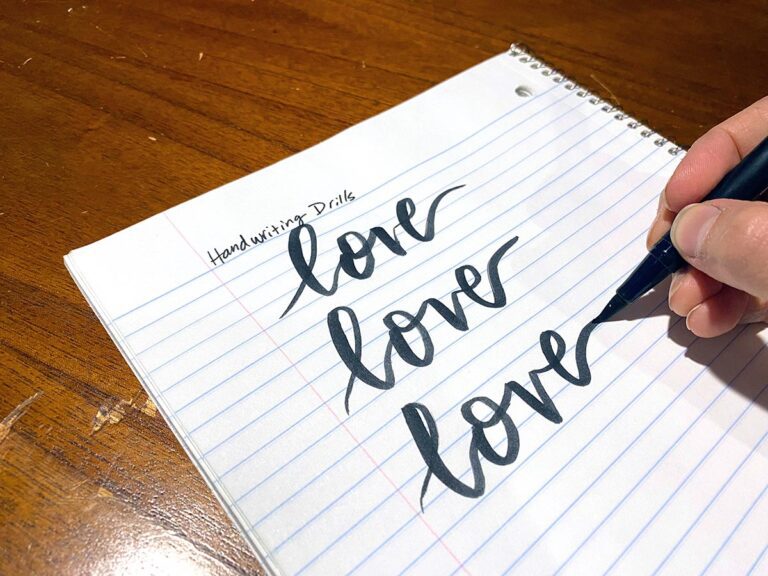

Zines are also an incredibly powerful method of sharing stories and communicating ideas. Part of this comes from the format, which feels more casual than a paper or presentation and less time-intensive than a full comic book. The tactile nature of drawing and creating the book is satisfying; putting pen(cil) to paper, then cutting and folding to make multiples is easy to do and quite accessible. Finally, making the students the authority on a topic helps build confidence and enthusiasm for the project.

How to Make Zines in the Art Room

Creating zines with your students is easy and fun. Just follow the steps below!

1. Brainstorm

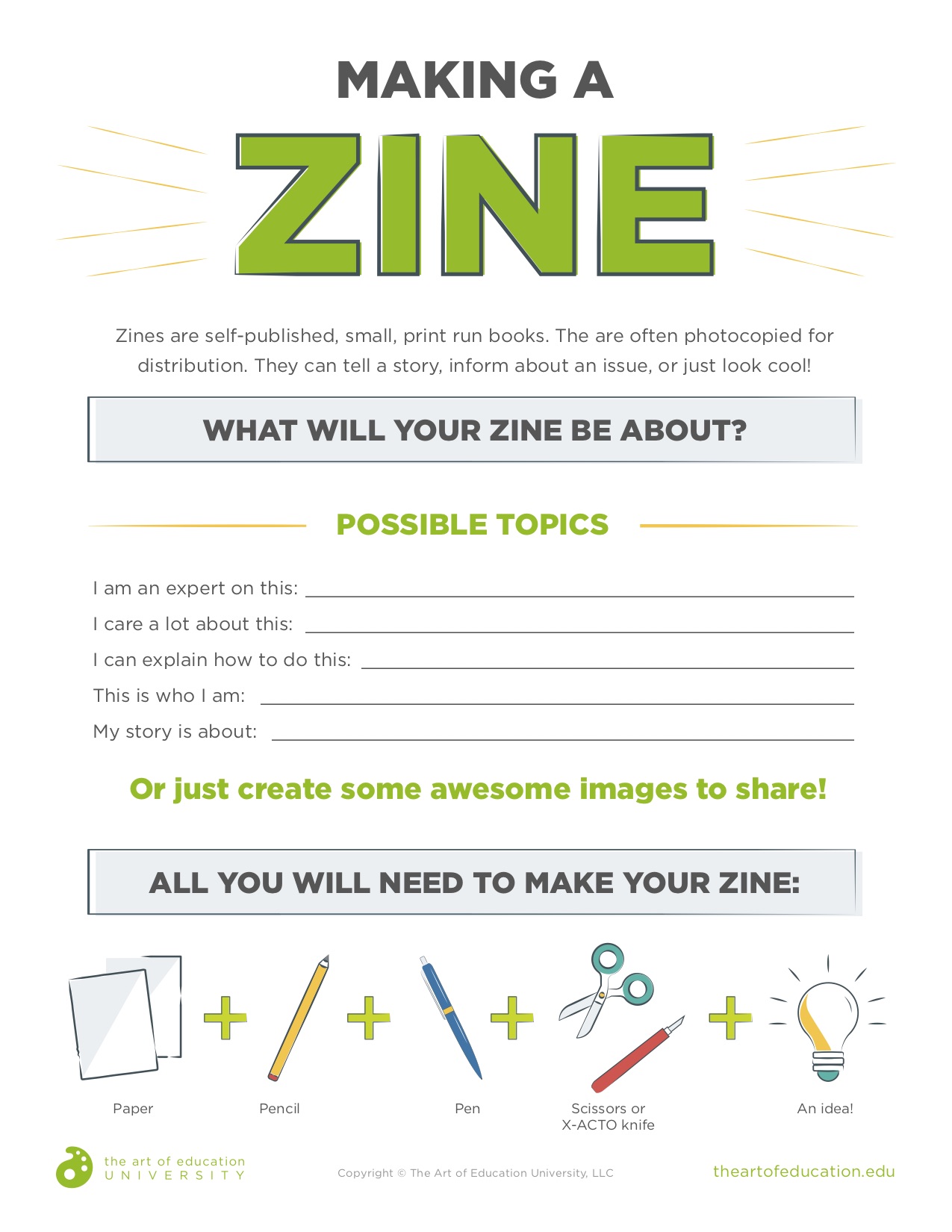

I encourage my students to start with a brainstorming sheet to consider what their zine should be about. You might have a range of strategies to help your students come up with topics for their projects, and any of those will likely work for zines.

Here are a few prompts which might help spur some additional ideas:

- I am an expert on:

- I care a lot about:

- I can explain how to:

- I see myself as:

- My all-time favorite is:

- I am struggling with:

If you’d like, you can download a brainstorming sheet to use with your students below!

2. Plan

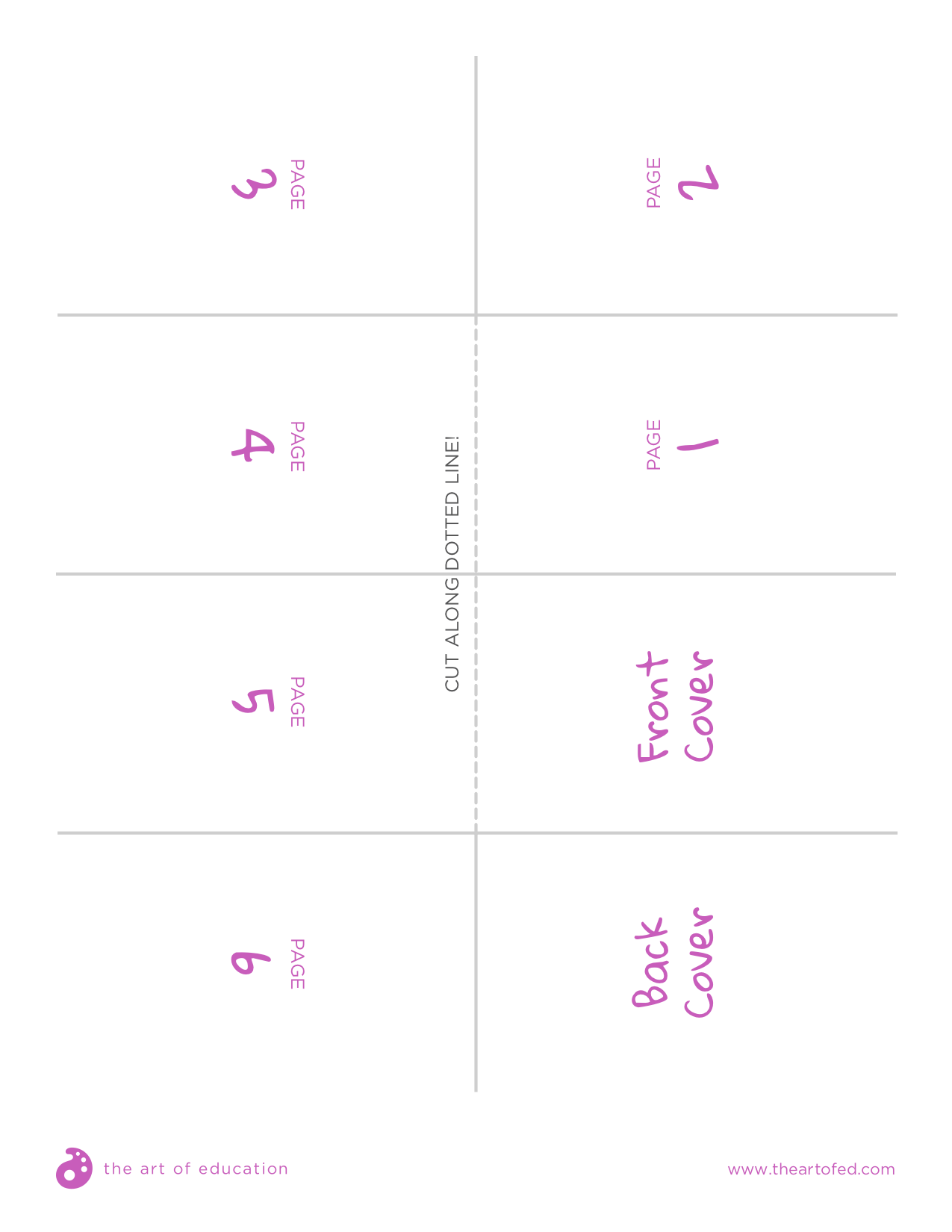

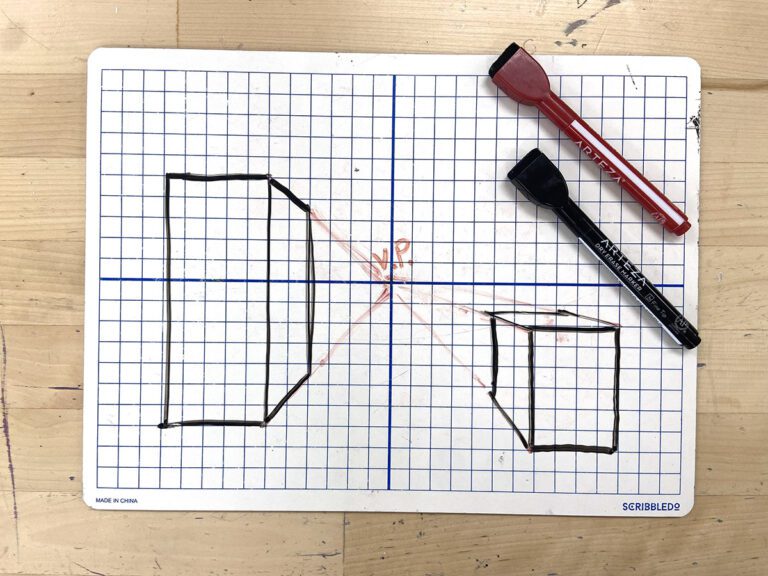

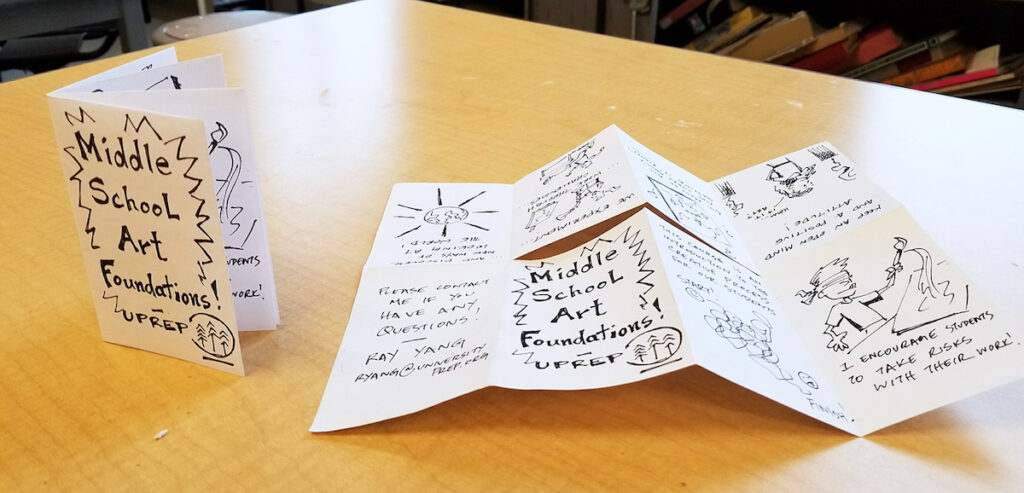

Once they’ve identified their subject, the real fun starts! Encourage your students to make a draft of the project before diving into the final piece. For the style of zine I’m suggesting, create an eight-panel draft sheet and have them start there. Some students work better writing things out first. Others prefer sketching ideas. Stay flexible and let them plot their story in whatever manner works best for them. Some great resources for visual storytelling methods can be found in Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics or Wally Wood’s 22 Panels that Work.

There’s a great download below that will show students exactly how to fold and cut their paper to make their zine.

Download Now!3. Draw

When the draft is done, you can begin working with them on a final document. Penciling the pages first is recommended, but sometimes students want to dive right in with pen. Once again, it all depends on their comfort with the process. A final document inked and colored (if you’ve got a color copier) gives the whole zine some polish.

4. Copy and Fold

Setting the project up to fit on typical letter size paper makes photocopying easy. After you’ve made copies of each student’s zine, you can have a folding party to make the final books. The folding process is quick once you’ve learned it. The site Experiment with Nature gives easy instructions for the zine format I use in my room. Putting aside some time in class for students to do the folding and cutting of their zines is a great way to celebrate the creation of their first “publication.” Bring some treats to share and make it a party!

5. Share your work!

Now that your students have created zines, it’s time to share them! Locate a space for your zine distribution in your school. The library is a great place to start, as students often spend time in the space browsing and reading. Lay out the zines for people to check out. And if your students are willing, be sure to include a “Please take one and share!” sign, so people know that they’re available to take home. You’ll likely find that students want to start making zines on their own and you’ve jump-started a way for them to communicate to the world!

The zines I’ve introduced are just one example of the format; there are endless online resources to check out like the Zine & E-zine Resource Guide and ZAPP Seattle. I encourage you to experiment and come up with your own styles while working with your students!

What types of publications have you created with your students?

How do you bring text and image together in your classroom?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.