Chances are, you took several curriculum writing, methodology, and pedagogy classes in your undergraduate education. You are an expert at writing lesson plans to fit the needs of your students while aligning to NCAS and your district’s scope and sequence. But did you know grant writing isn’t that much different?

Learn how to tap into your curriculum writing skills to advocate for your students through grant writing. Gain unique insight and develop opportunities to grow your program in fun and exciting ways!

What is a grant?

Erin Saladino is AOEU’s Learning Experience Designer. She has 17+ years of experience as a visual art and theater teacher and county art supervisor. Erin describes a grant as “an investment made by stakeholders toward needs-aligned projects.” Furthermore, each project’s ultimate goal should be to make a change.

Let’s break it down even more. A grant should have the following three components:

- Stakeholder investment

- Address a specific need with a project goal

- Make a change or impact

If you are looking to improve your curriculum and bring innovative learning opportunities to your students, take a look at our new Master of Education in Curriculum and Instruction (MEd). Specialize in Instructional Leadership in Art Education and take our Principles of Art and Business online course to capitalize on grants and make the most of your budget. Grow your impact in the art room and enhance your art program. Talk to an admissions counselor today to learn more.

Get in touch with an admissions counselor!

Make grant writing easy with these thirteen steps.

1. Identify a specific need and art project.

The first step is to identify a specific need. Hand in hand is figuring out the perfect art project to pair with it. Be sure your need is specific to you and your students. It should not be a generic ask for art supplies.

Communicating with site stakeholders is important when identifying needs and the creative solutions your art program can bring to your school. When you start the grant process, it is best practice to communicate your plans with the administration. Usually, this chat isn’t to ask for permission but to make them aware of your go-getter approach and keep them in the loop about what is happening in your art room. School-focused grants usually require a signature from your administrator down the line, so let them know you are on a mission now.

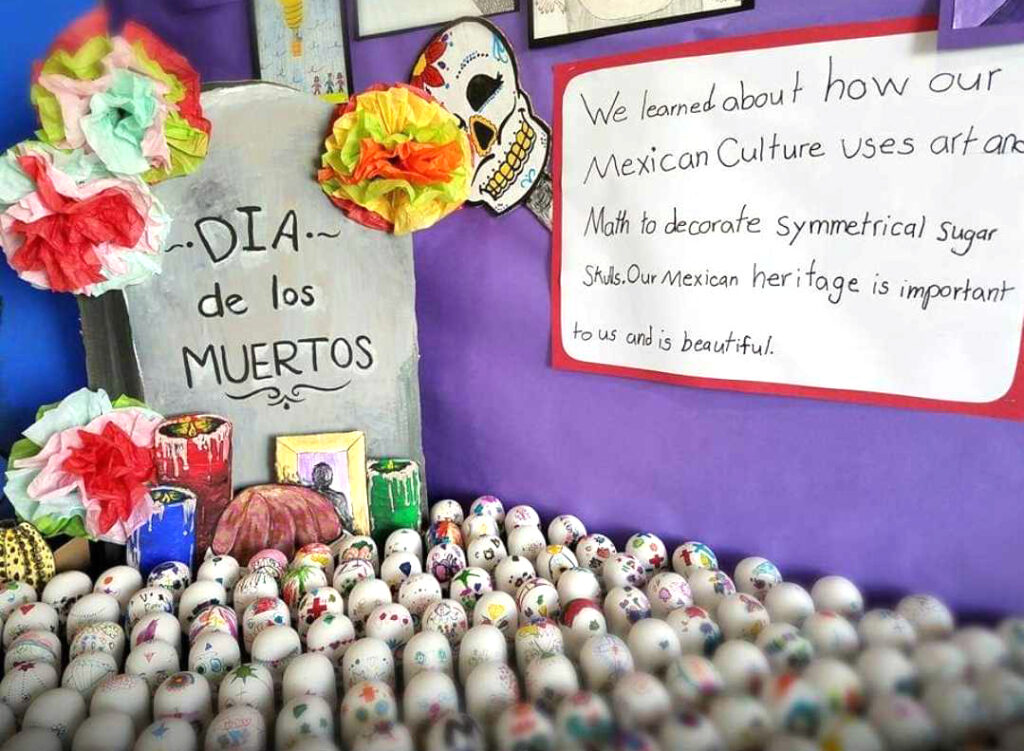

Perhaps your school has a large first-generation Latinx population, primarily from Mexico. The students are growing up in the United States and are out of touch with their Latinx roots. The need is to infuse Mexican culture into the art curriculum. A specific fifth-grade art project to meet this need can be designing Day of the Dead sugar skulls. Take the time to determine your need and project so you can figure out the right grants to apply for.

2. Investigate big-picture connections.

Now that you have a project identified, it’s time to look at different areas of connection. Consider cultural and social ties and how they correlate to standards such as NCAS. It’s wonderful if your project has cross-curricular connections that can anchor it to core content areas for greater impact. Ensure your project objectives reflect the standards and connections. Notate if you are required to use a specific curriculum or set of standards. Erin suggests avoiding political connections because they can be sensitive and tricky to navigate.

Here are Florida state standards for our 5th-grade project:

- Culture & History (Visual Art and Social Studies standards)

VA.5.H.1.3 Identify and describe the importance a selected group or culture places on specific works of art.

VA.5.S.1.3 Create artworks to depict personal, cultural, and/or historical themes.

SS.5.A.1.1 Use primary and secondary sources to understand history. - Personal Voice & Communication (Visual Art standards)

VA.5.O.3.1 Create meaningful and unique works of art to effectively communicate and document a personal voice.

VA.5.F.1.2 Develop multiple solutions to solve artistic problems and justify personal artistic or aesthetic choices. - Critical Thinking & Organization (Visual Art and Math standards)

MAFS.5.G.2.3 Understand that attributes belonging to a category of two-dimensional figures also belong to all subcategories of that category.

VA.5.C.22 Analyze personal artworks to articulate the motivations and intentions in creating personal works of art.

3. Hone in on the student impact.

It’s vital to be able to tell a story. You need to be able to share how the proposed project will impact the students. Accurately doing this requires research and forethought.

Let’s elaborate on our Day of the Dead example. Procuring real sugar skulls for the entire fifth grade will have a huge impact. Students will be able to make cultural connections to their parents and extended families. Parents and family members can step into their students’ learning by sharing family histories and family trees. Students will have increased pride in their Latinx roots and community. Students will gain representation in their educational experience, which will be reflected in the curriculum.

Research to support this can be a needs pre-assessment as part of the students’ first-day packet. Ask questions to garner insight on how much they know about their heritage and where their families are from. There are two forms of data you can collect: qualitative and quantitative. Qualitative data includes testimonies, drawings, and experiences and can convey a “human” connection. Quantitative data include numbers and percentages. Both will take a little preplanning, so build intentional data-collection activities into your agenda.

4. Explore grants.

There are tons of grant opportunities out there—you just need to find them. But how do you go about doing that? Aside from word of mouth and a quick internet search, reach out to your district’s grant writing department. Regardless of size, most districts have a grant writing department. It can be a team of people or one person who specializes in this area. Either way, your grant writing department will have resources to share and may even reach out on your behalf.

5. Target your asks.

There are also different sizes of grants. Some come from large corporations, like Target or Walmart, and have a large applicant pool. Some come from smaller organizations, like your local arts council, and have a much smaller applicant pool. There is no right or wrong choice. However, it is wise to consider your chances. Will you get lost in a sea of applicants, or will you stand out? Should you reach for the stars or tap into local organizations?

For the Day of the Dead scenario, research grants that target Hispanic heritage or the importance of cultural awareness. Some grants have narrow specifications that may give you an edge over more generalized ones. The applicant pool may also be smaller, giving you another advantage.

Erin cautions that you must use your demographics appropriately and as a strength. Use your data and words to intentionally tell a story that showcases your students in a positive light. Focus on how the grant can meet the need, impact your students, and reflect positively on the organization funding the grant. Defining our students by their demographics and focusing solely on the project’s need can often be detrimental. There is a fine line between telling a moving story and exploitation.

6. Write the grant proposal.

It’s time to sit down and write the proposal! While you want to tell a story that conveys you and your students as humans, write in a professional and formal tone as if you are writing for your administration. This is not a blog or social media post but rather an important document to capture researched data, project planning, and a request. Include all the connections, standards, and research you took the time to capture and gather. Focus on the big “why” or impact throughout the proposal.

7. Sell yourself as a personable professional.

It can be easy to forget your “professional” side when you are covered in paint and clay all day long. But remember, you are a professional! You have the credentials to teach and a passion for art, and no one knows your students better than you. You are also personable because you are a real person behind the paperwork.

When you write the proposal, frame yourself as a personable professional who is reliable and worth investing in. At the end of the day, your name is on the grant application, so you are the face of the project. The organization will brag about giving it to YOU.

Erin shares four things you can slide into your proposal to frame you as a personable professional:

- The number of years you have been teaching.

- Related interests, studies, or experiences that tie into your project’s focus to show expertise and real-life connections.

- Personal viewpoint on the importance of community connections that conveys how much you appreciate them for their grant offerings.

- Student-free photos of your art room, art show, or previous community project.

8. Budget enough time.

The grant writing process can be lengthy and may be overwhelming or scary. Just start writing and budget enough time, and the process will go faster than you anticipated. Before writing the grant proposal, give yourself a month to research and gather data. Give yourself another month to compile the data and fill out the application. If you are still unsure when to start, work backward from the deadline.

9. Submit to multiple grants.

If you made it this far, you have done so much work! Get the most out of the time and effort you poured in and submit your proposal to multiple grants. If you don’t hear back or don’t move on in the process, it’s okay to submit the same proposal the following year. Tweak the goals to reflect your most current data and demographics. After all, it is a competition. You never know—you could have been in second place. It can be well worth it to apply again.

Did you find a great grant? If you have the time, energy, and an additional winning project or two, multiply your odds by submitting more than one project proposal. Erin says it’s okay to submit up to three times with three different projects to one grant unless they specify otherwise. Additionally, why put all of your eggs in one basket? You have done the work, so explore other grants to apply with the same proposal. Grants rarely say not to submit to another. You may even win more than one grant for the same proposal! This is awesome and a way to impact a larger group of your students.

At the end of the day, it’s encouraged that you submit as much as possible, but be sure to read the fine print. This includes your own fine print. Stakeholders want you to approach them specifically. If you apply to multiple grants with the same project, make small tweaks to customize the proposals according to each grant.

10. Wait for responses.

And then you wait. With local organizations, you will generally hear back in two weeks. Larger grants from big corporations may take a month, or you may not hear back. If you don’t hear back at all, don’t worry, and don’t give up! Save your proposal for another grant application this year or next year.

11. Save your recipe.

While you wait, organize and save your documents in a safe place. Know where they are filed so you can use them the following year to either reapply for a grant or use the formula to plug in a new project!

12. Document the process.

If your grant proposal was approved, let the project begin! Document the entire process. Documentation includes receipts, pre-assessments, post-assessments, photos, videos, and more. It’s always better to over-document. You can file away the photos and information you don’t need. It’s harder to come up short and wish you had taken more pictures or gotten more student feedback along the way.

Be transparent and share documentation with all involved parties, including your administration. This is a chance for them to see how you shine! Most grants will require you to submit receipts and photos of the final artwork at the bare minimum. Adhere to your district and school guidelines for sharing student work and photos.

13. Give thanks.

An authentic “thank you” goes a long way. The organization or corporation that awarded you and your students the grant loves to see the impact they made! They are more apt to contribute in the future if they see a lasting impact. It also teaches your students gratitude and how to express it.

Here are four ways to show your thanks:

- Share student testimonials.

- Snap photos of students holding their art projects.

- Show a large amount of artwork for an impressive “wow” factor.

- Create a short video “documentary” to highlight the project from start to finish.

Going back to our Day of the Dead sugar skulls example, a fabulous thank-you photo would be to lay out all of the fifth grade’s sugar skulls on a large table or the floor and snap a photo. The sheer amount of sugar skulls visually testifies to how many students and families were impacted by the grant.

Any last-minute advice?

The best way to become more familiar and comfortable with grants is to just do one! Erin sums it up with three pieces of parting advice. First, take the process “one step at a time, one bit at a time.” It’s manageable and you can do it! Second, submit as many grants as you can. If you are putting in the work, make it count. And lastly, create and save your recipe. Once you have a formula that works, keep using it year after year. Harness the skills you already have as the amazing art teacher you are and use grants to bring new, intentional, and meaningful learning opportunities to your students.

Portions of this work are based on the National Core Arts Standards. Used with permission. National Coalition for Core Arts Standards (2015) National Core Arts Standards. Rights Administered by the State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education. Dover, DE, www.nationalartsstandards.org all rights reserved.

NCAS does not endorse or promote any goods or services offered by the Art of Education University.

What is your experience with grant writing in the art room?

What advice would you add to this list?

Share a neat grant project you were able to do with your students!

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.