The world of art theft, heists, and cons is fascinating. These stories of crime don’t only fascinate art lovers; they also intrigue those uninterested in art. Television shows and movies like White Collar and Contraband make for great entertainment, but these occurrences are not merely fictional accounts. Art crime has existed for centuries and continues today. Many people know the stories of the Mona Lisa theft, stolen artwork by the Nazis, or the greatest unsolved heist at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Yet, lesser-known investigations and art crimes occur in modern times as well.

If there’s one way to hook our students on art history, discussing art crimes is a start! While it’s rather interesting that with advanced technology, thieves still manage to steal artwork from museums, the world of forging and conning art still runs rampant. Modern stories of forgery in the 21st century can intrigue students.

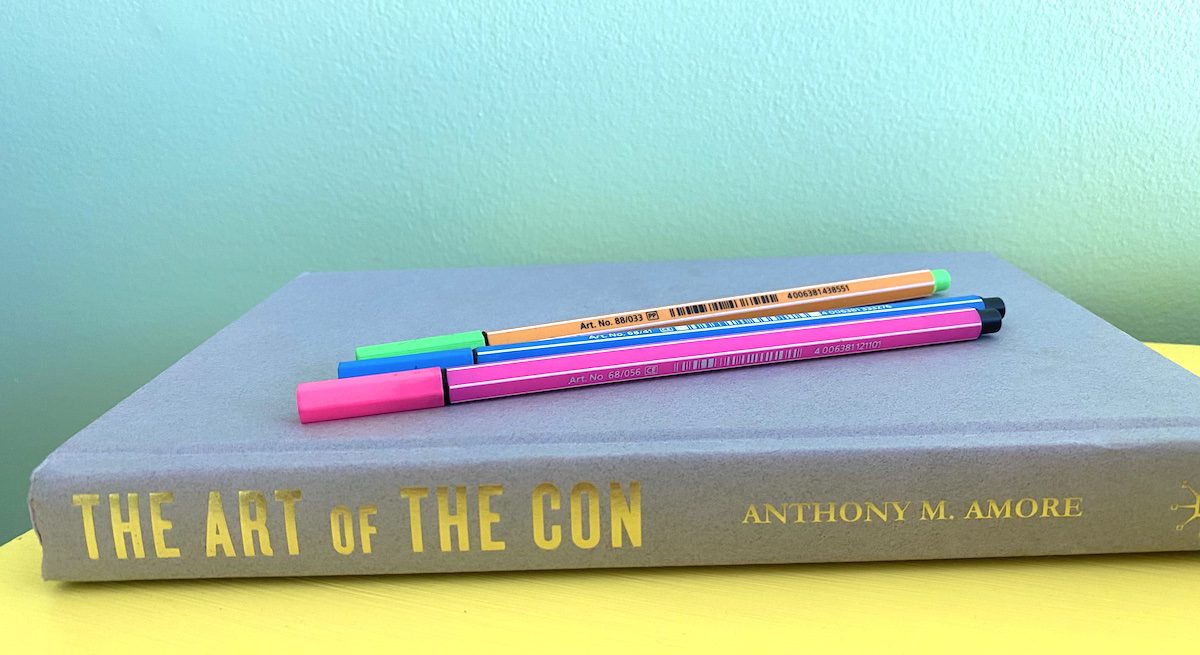

Anthony M. Amore’s book, The Art of the Con (2015), examines notorious yet untold art forgery stories, fraud, and crime. The book includes research, facts, and details of the investigation of some major art crimes occurring in the 20th and 21st centuries. While discussing art crimes might engage students, it must have a purpose in the classroom. We don’t want to send our students the wrong idea that art fraud and forgery are okay! Anchor Standard 5 from the NCAS connects with discussions about art history, presentation, and restoration.

Anchor Standard 5: Develop and refine artistic techniques and work for presentation.

Enduring Understanding: Artists, curators, and others consider various factors and methods, including evolving technologies, when preparing and refining artwork for display and/or when deciding if and how to preserve and protect it.

Essential Question(s): What methods and processes are considered when preparing artwork for presentation or preservation? How does refining artwork affect its meaning to the viewer? What criteria are considered when selecting work for presentation, a portfolio, or a collection?

Here are two stories of art forgery and an activity to get your students thinking.

1. The Forgery of Wolfgang Beltracchi

Certain people have the gift of impersonation. Whether it be for comedic purposes or entertainment, some individuals can sound just like anyone. Wolfgang Beltracchi is a German art forger of impression. Beltracchi did not simply recreate paintings that already existed. Instead, he created artwork he thought artists would create using their style. He also depicted lost art missing from catalogs with no image attached to it. He notably did this for a forged painting he created in the style of Surrealist artist Max Ernst. It passed as a painting created in 1927 and eventually sold for $7 million.

Beltracchi had great success forging paintings from 1970-2010 until he was eventually caught and served a short prison sentence. The police were able to uncover fifty forged paintings, but many others appear to be lost. Wolfgang says he created over 300 forgeries during his career as an art forger.

Beltracchi’s work was a family affair; his wife Helene would often help scheme and create backstories for the forged artwork. In one instance, Helene posed as her grandmother in front of forged paintings that mimicked Max Ernst and Ferdinand Leger’s work that Wolfgang created. Using an old fashioned camera and sepia tinting, the image passed as an old family photograph, giving the impression that these artworks were a rich part of their family history. After serving in prison for just three years, Wolfgang has seemed to find success. He was found guilty of forging only fourteen artworks resulting in $45 million, yet it’s believed that during his career as a forger, he made over $100 million. Today you will find him creating original artwork, finally using his own name.

10 Weird and Wonderful Art History Stories You Need to Know

2. The Forgery Story of Pei-Shen Qian

In 1981, a Chinese art student came to the US with a visa to study art. Pei-Shen Qian produced such high-quality work that his teachers doubted his skill, and he was often accused of not creating his own work or cheating to get ahead. After his schooling, he went back to China and became a successful professional artist. His first job was a mundane role appointed by the government during the Cultural Revolution. After the revolution, he was part of a major exhibit in Shanghai credited with the rebirth of modern Chinese art.

With this experience, he wanted success and went back to New York City. While there for a second time, he didn’t receive the notability and praise he had in Shanghai. While he was making more money, he found himself peddling his paintings on the city’s streets.

That was until Carlos Bergantinos came along in the early 1990s. Bergantinos recognized Qian’s skill and asked him to replicate a modern artwork for $200. Bergantinos continued to pay Qian to recreate paintings by Abstract Expressionist artists such as Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, and Willem de Kooning. Mimicking the signature wasn’t enough, so aged canvases and materials were sought from flea markets to fit the original work’s time. Artificial aging methods like using tea bags or using a blow dryer to heat them increased the authenticity.

Art dealers Carlos Bergantinos and Glafira Rosales created elaborate backstories to sell these forged paintings. They created the presence of an anonymous collector, Mr. X, along with stories of a Spanish collector with forged documents and paintings to go along with it. Esteemed gallery, Knoedler & Company would buy the story, the artwork, and the forgery that came with it.

The gallery continued to buy forged paintings from Rosales, and in March 2001, they purchased a 1949 Jackson Pollock painting for $750,000. Just two months later, it would sell for $2 million. The authenticity of the painting was questioned and returned. Yet, Knoedler unknowingly continued to purchase forged artwork from Rosales until the oldest gallery in New York City abruptly closed in 2011 after many lawsuits.

It really is a story out of a movie!

The gallery spent $80 million on forgeries created by Qian, while Bergantinos and Rosales walked away with $33 million until the US government discovered their wrongdoing, and they were indicted in 2014. The two most interesting parts of this story are that Qian, now 80, fled back to China, escaping arrest, claiming he had no knowledge of what had occurred and at the time didn’t even recognize the work of the modern artists. Yet, by 2008 it is believed that Qian was receiving $7,000 for each forged painting.

The other questionable part of this story is that of the Knoedler & Company gallery. After the first instance of a questionable painting in 2001, why did they keep buying from Rosales? Did they knowingly sell millions of dollars in forged paintings to buyers? Ann Freedman, the art dealer at Knoedler, would say this is not the case. She eventually disclosed that she bought a painting herself and noticed Pollock was misspelled as “Pollok.” Yet, conservators from the Mark Rothko Foundation passed Qian’s forgeries as Rothko originals.

A Surefire Way to Make Art History Less Boring

3. An Art Activity for Students

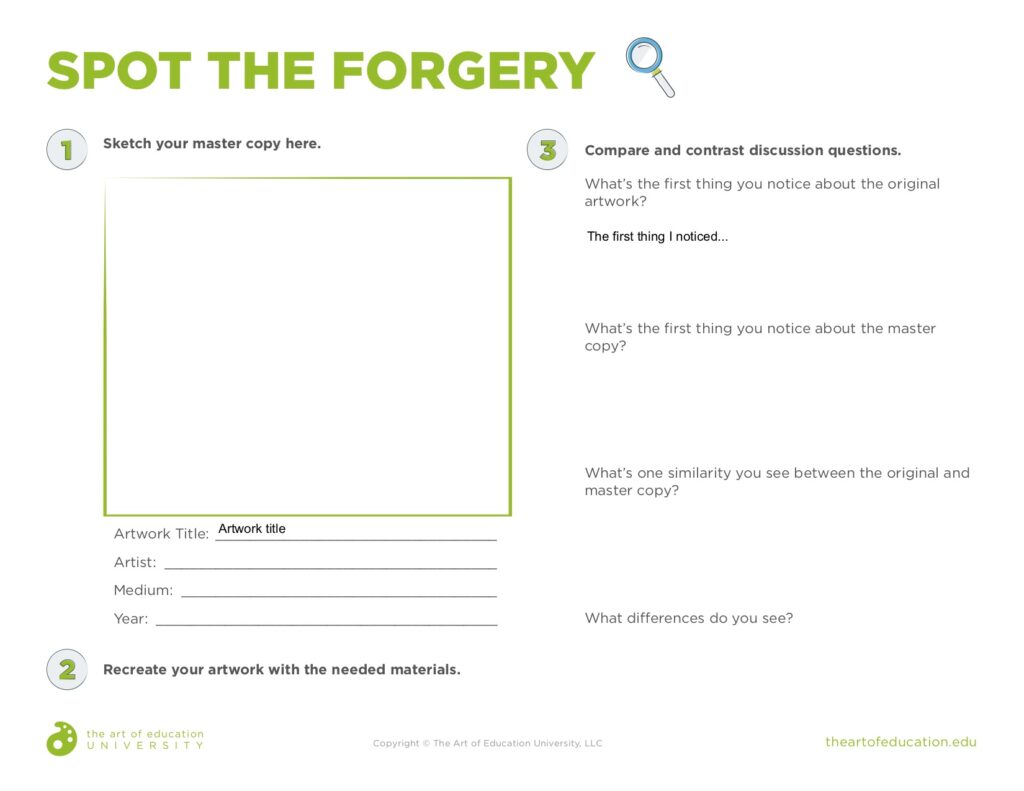

Download this editable activity for your students.

While forgery isn’t a practice we should be teaching in school, students can learn from creating master copies. Use this handout to help your students refine their skills and learn from an artist of their choice by recreating one of their works. For an added discussion, use the guiding questions to spot the forgery! This is a fun way for students to compare and contrast the artist and student copy.

One way to increase student interest in art history is by introducing students to art crimes and forgeries. The stories behind some of these crimes capture the imagination and, with a little luck, can connect nicely to standards already being taught in your art room.

What art cons and crimes have always intrigued you?

How do you discuss art fraud and forgery as part of art history in your classroom?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.