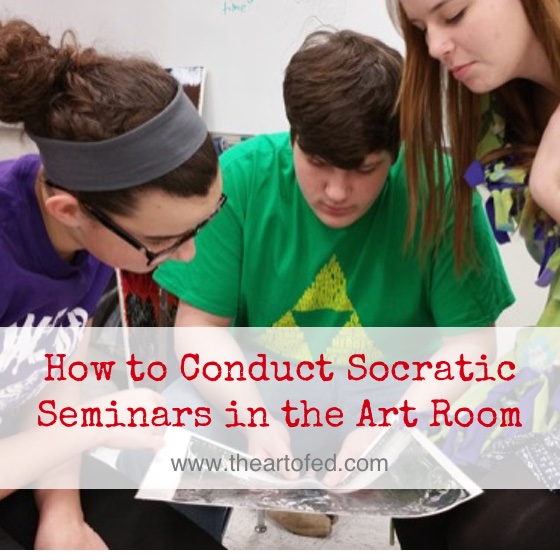

For those who aren’t familiar with the concept, a Socratic Seminar is a classroom discussion that focuses on big ideas and involves all students. It is basically the antithesis of a lecture–instead of transmitting knowledge from teacher to student(s), we are instead sharing our ideas through dialogue. Not debate, but dialogue. We are not covering a topic, or focusing on subject matter, we are exploring these things. We are not looking for right answers, and we are not looking to change anyone’s mind. We want to extend ideas, explore thoughts, and work collectively to think more deeply about those big ideas.

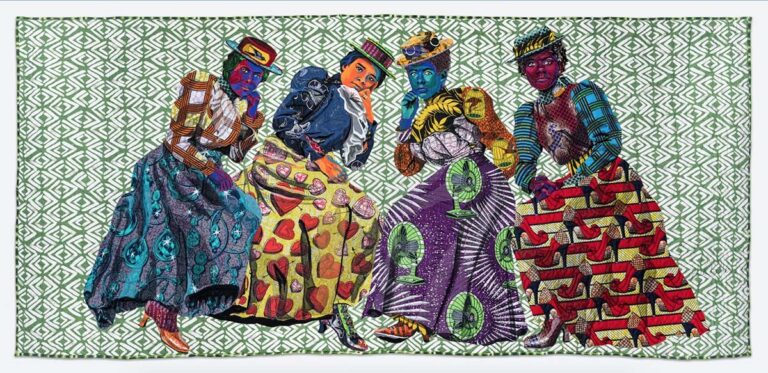

Seminars are generally based on a text, and at times, we will use a text. More often, however, I will set up our discussion based on a particular artwork. Read on to see how I set up and run Socratic Seminars in my art room and why I think they’re so important.

Setting Up the Classroom

Students should be set up in a circle. My tables are in a ‘U’ shape, and that works well enough. The important part is that everyone can see and hear each other, so each student feels comfortable being a part of the seminar.

Setting Up the Discussion

I will find an artwork to discuss that either has an ambiguous meaning, or a deep meaning that is worth discussing at length. Probably my favorite is the etching Minotauromachia by Picasso, but it’s tough to go wrong–especially if your kids are used to talking about work.

After selecting the artwork, I choose a big idea (from the list of 103 great ideas from Mortimer Adler). This big idea will begin and guide our discussion. Within this idea, you should be looking for 3 things.

1. Ideas, Issues, and Values–Find some that are worth talking about.

2. Ambiguity–Your big idea should allow for multiple positions, ideas and opinions.

3. Accessibility–Choose an idea that is interesting for your students. It really, really helps if you are interested in it as well. If you are curious and inquisitive your students will be too.

Conducting the Discussion

Using the big idea, I will begin with an opening question. This question WILL NOT have a right answer. It should reference the artwork (or text) we are using, and have students explore the deeper meaning of the work. Often times, this is a good spot to use some higher-order thinking skills. For example, you could ask, “After looking at the artwork, please rank these pairs of emotions according to their relevance to the work: Courage v. Despair, Love v. Fear, and Respect v. Pity.”

From there, it’s all about simply guiding the discussion. When you run a Socratic Seminar, you are both the leader and a participant. You will ask the questions that get them talking, and you will talk yourself, but make sure you have these things in mind:

- Silence is OK! Taking time to think and formulate responses is important.

- Keep the discussion focused on the art.

- Ask follow-up questions. Paraphrase, probe and make students expand ideas.

- Help clarify if answers or thoughts get bogged down, confused, or vague.

- Involve reluctant students, and move away from those who dominate the discussion.

Now, one opening question and a few follow-ups will generally not give you an entire class period of discussion. This is especially true when you are in the first few seminars of the year. To move things along, I go to a “How” or “Why” question–anything open-ended that can keep the conversation going strong. For example, you could ask, “Why do you think Picasso chose the minotaur for this work? How could that be representative of a bigger idea?”

If the conversation really stalls, I like to use some generic questions like asking students’ opinions, having them come up with some kind of hypothesis, putting themselves in the artist’s shoes, etc. Anything that you feel is worth discussing probably is worth discussing. Just put a little bit of thought and planning into the questions you will ask before you get started.

Learning Together

Socratic Seminars are not something you can jump right into. It takes time for both you and your students to learn to do them well. The beauty is that you can learn together. Each time you conduct a seminar, you will learn what kinds of questions to ask to draw out reasoning and explanations from your students and your students will learn how to speak, read, listen, observe and defend opinions without debate.

It can take quite a few class periods to get to the point of seamless seminars, but I feel like it’s a great way to study art history, especially for my advanced students who have some prior knowledge.

Because of Socratic Seminars, my students are better at analyzing, communicating, thinking, and speaking–all skills that we, as art teachers, would likely say are beneficial. Most importantly, I am of the opinion that the critical thinking, original thoughts, and initiative that are developed in these seminars help my students become better artists. And that’s the goal I’m really after.

Have you ever tried a Socratic Seminar in your art room?

What are some of the other types of discussions and critiques that take place in your room?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.