With everything you have to fit into your curriculum, do you ever feel like some things just fall by the wayside? Whether it’s specific projects or larger concepts, there often isn’t time to “do it all”. One thing that was always difficult for me to find time for was analyzing artwork. Especially with short classes at the elementary level, teaching students how to look was something I often rushed through, spending two minutes here or there, rather than really taking the time to dig in. I knew I was doing a disservice to my students, as becoming a careful observer is an important skill to have as an artist.

I recently spoke to Briana Zavadil White, Manager of Student and Teacher Programs at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C., to learn more about looking strategies for the classroom. She not only helped me see that teaching students to dissect a piece of work is extremely important but that it can be fun and engaging too.

Today I’ll take you through the concept of Slow Looking as well as 5 other quick looking strategies that you can use in your classroom.

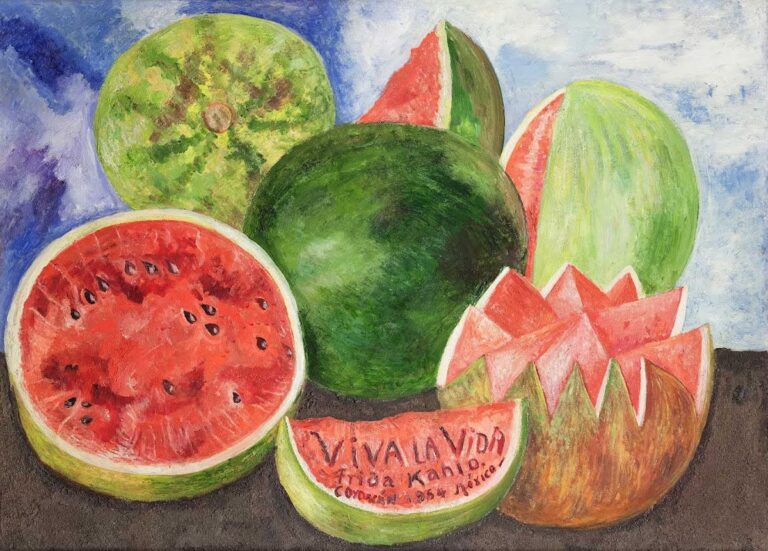

Slow Looking

Engaging in Slow Looking is kind of like putting your classroom in a time out. It is the process of dissecting a single image or artistic object detail-by-detail with your students and is something that Briana and other museum educators lead students and teachers through when they visit the museum.

According to Briana, when people visit a museum (or when you present a piece of art to students in class) most people want to read the label first. They want to know who the piece is by, the title and the media. However, she says, “… in our programs, we tell participants to stay away from the label. The portrait itself will tell us so much. The students (or teachers) just need to learn how to tease out the visual information presented in the portrait.”

If you’d like to try Slow Looking in your art room, here’s how to go about it.

1. Choose a class period when you will have at least 15 minutes to spend looking and discussing.

Coming from the elementary world, I initially thought that sounded a bit long, but Briana assured me that she will often spend 45 minutes with a group of students on one object!

2. Choose an image to present to the students.

It could be related to the project you’re doing, a preview of your next project, or simply something you’d like to discuss with your class.

3. Do NOT tell the students about the artist, medium, or title.

Remember, the piece will tell you so much!

4. Use The Elements of Portrayal as a starting point.

With portraiture, National Portrait Gallery educators have visitors focus on what they call The Elements of Portrayal: pose/posture, facial expression, clothing, hairstyle, setting, objects, scale, medium, color, and artistic style. Depending on the piece you present to students, you may not have all of these elements to consider, or may add a few of your own. Choose the elements that will lead your students to the story.

5. Prompting students with questions related to the elements of portrayal, guide them through a discussion.

The beauty is that whatever story your class comes up with is ok. There is not necessarily a right answer. The exercise is about learning to look.

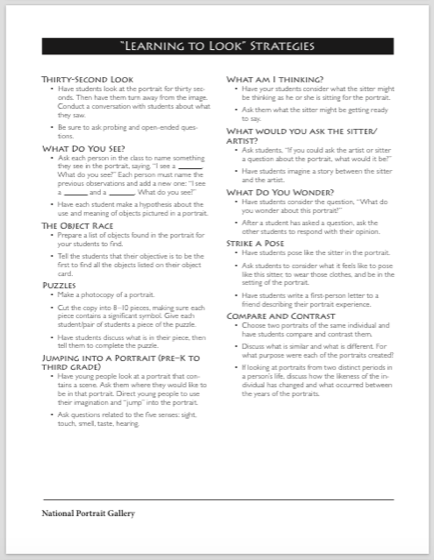

5 More Simple Looking Strategies

In addition to Slow Looking, Briana and her team also use many other looking strategies to help students and other visitors dive deeper into artwork. Using some of the gallery’s pieces, I’ve detailed 5 more looking strategies to use in your classroom below. The great thing about using pieces from the Portrait Gallery is that they all have biographical and historical cross-curricular connections, as the museum is dedicated to helping tell the story of America and its people.

Many of these ideas come directly from the Reading Portraiture Guide for Educators, which is available to download for free at the end of this article.

1. The 30 Second Look

This activity is great if you’re short on time. Have students study a piece of art for 30 seconds only, then cover the image or turn off your projector. Conduct a discussion by asking students what they remember using open-ended questions. Less-busy pieces, like the portrait of George Washington below, make great choices.

2. Puzzle

This activity forces students to carefully consider just a small portion of an image before seeing how it fits into a whole. Photocopy a piece of art, then cut it into pieces, making sure there is something significant in each. Divide students into pairs or small groups, with each group receiving a piece of the puzzle. For each pair/group, ask students to study their pieces and describe what they’re seeing to the other groups, then have the students assemble the puzzles and discuss. Pieces with lots of interesting details, like Christian Schussle’s Men of Progress, work well.

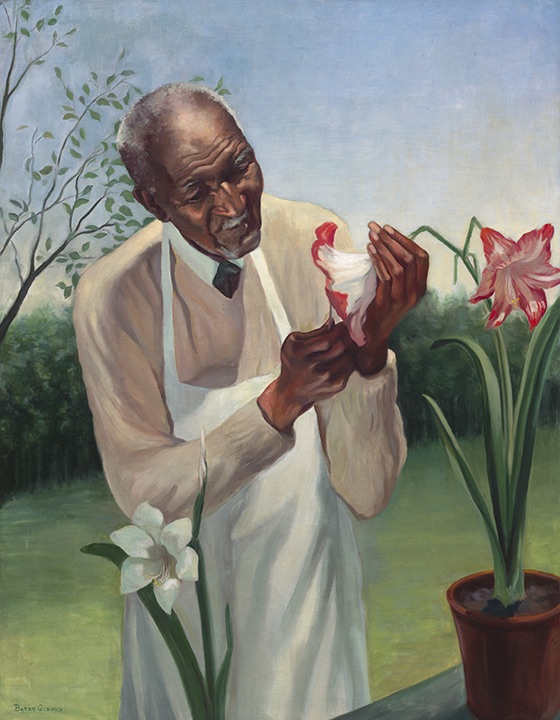

3. Jumping Into a Portrait

“Jumping In” is a great activity to help younger students start to really look at a piece of art. Have students study an image, then ask them to imagine jumping right into it! Where would they like to land? Why? What else would they see once they got into the picture? Ask them to think about all of their senses. What do they hear? What to they smell? Pieces that lend themselves to this kind of thinking, like George Washington Carver by Betsy Graves Reyneau, are fun for students to consider.

4. Compare and Contrast

While the other strategies mentioned here work with many types of artwork, this one works especially well with portraiture. Have students view two portraits of the same person. It could be two self-portraits, two portraits, or one of each. Ask them to compare and contrast the two images. One great question to get your students thinking is, “Why was each portrait created? What is the purpose of each?” Choosing portraits from different time periods in a person’s life adds another element to this activity. One thought-provoking example would be the two portraits of Pocahontas below.

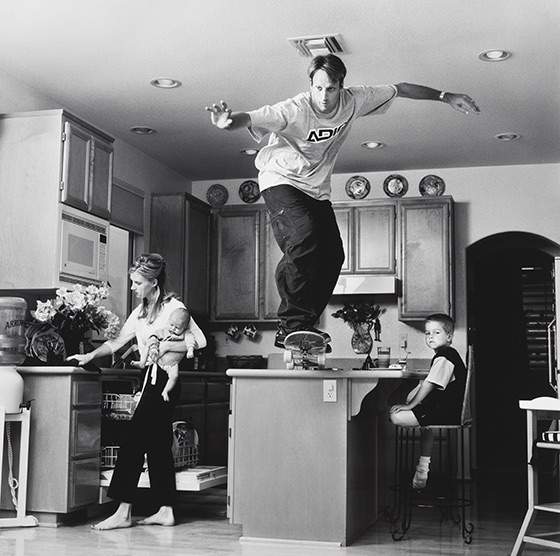

5. Think, Puzzle, Explore

Think, Puzzle, Explore aims to open up students’ curiosity. When looking at an image, such as Tony Hawk by Martin Schoeller, students are asked to ponder three questions:

- What do you think you know about this artwork?

- What questions or puzzles do you have?

- What does the artwork make you want to explore?

The goal is to get students to move beyond simplistic answers and really tease out some specifics.

If you’re interested in learning even more about specific looking strategies, the Reading Portraiture Guide for Educators is packed full of tips for you. Courtesy of the Portrait Gallery, you can download it for free by clicking below!

In addition, the National Portrait Gallery offers a wide-array of fantastic programs for both students and educators. If you’re interested in learning more about these programs, including the popular Summer Teacher Institutes where you can learn about looking strategies first-hand, please head on over to the museum’s Education page.

With all of the techniques, projects and concepts we have to fit into our curriculums and schedules, teaching students how to look can sometimes fall by the wayside. Hopefully these activities will help you remember that digging deep into a piece of work has many benefits. Students may find that they enjoy becoming art detectives, discerning the meaning of an image from visual clues, and you may find that your students are much more insightful than you thought. Slowing down is a great change of pace and one that all of you will appreciate!

A special thanks to the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C. and Briana Zavadil White for sharing their expertise!

Tell us, how do you help students learn to analyze artwork?

Do you have any activities to add to this list?

What are some pieces that you like to have students talk about?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.