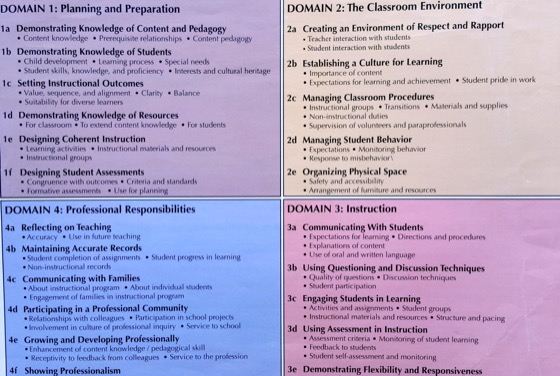

If your school district is anything like mine, it seems like new ideas and initiatives are rolled out on a whim with little to no explanation. That happened to me when we switched to a new evaluation model a few years ago. As the Danielson Evaluation Model made its trial run through the district, there was little discussion about what it was or why we were switching. For those who are unfamiliar, the Danielson Model focuses on four domains: Planning, Classroom Environment, Instruction, and Professional Responsibilities. Teachers are scored on components and elements found within each domain, from 1 (Needs Improvement) to 4 (Exceptional).

I was initially skeptical of the idea and skeptical of a new evaluation model. I found, however, that I actually really like the Danielson Model and I think it lends itself well to what we do in the art room. It takes subjectivity out of the evaluation process and gives you quality feedback about your teaching; it has helped me reflect on and improve my own practices immensely. Today I’m sharing some advice about making the Danielson Model (or just about any observation process) work for you.

1. Nail Your Pre-Observation

I don’t need to tell you that many administrators are not as in tune with the arts as we would like. If your evaluator is familiar with what happens in the art room, fantastic. If they are not, it is your responsibility to educate them. The pre-observation (or planning) conference is the best chance for this to happen–make sure you are part of the discussion. If your system doesn’t require a pre-observation meeting, ask for one! The more educated your evaluator is about your processes in the art room, the better. This meeting is your chance to explain your teaching philosophy including what you teach and why you teach it. You may also want to point out the similarities and differences between the art room and other rooms in the school.

For example, in my classroom, I use anticipatory sets, go over objectives, and lead students through direct instruction and guided practice. Then, students do independent work. We discuss, we reflect, we clean up, and we have closure. All of these things are also done by other colleagues throughout the building. The difference is that in the art room, we are offering an expressive, creative experience for our students. Pointing out these connections can help your evaluator embrace the slightly more chaotic nature of your classroom. Giving them this information up front will allow them to enter your classroom with the right mindset to view what is happening.

2. Take the Pressure Off

Far too many teachers work themselves up and stress themselves out over evaluations. Sometimes, they feel like an administrator just won’t “get” what they are doing. Sometimes there is tension between art teachers and non-art administrators and evaluators. Sometimes it’s a scheduling issue. However, ideally these things should not matter. An effective evaluation system, like the Danielson Model, strives to take subjectivity out of the evaluation process. Let’s face it: good teaching is good teaching, and a successful evaluation model will reflect that no matter the circumstances. Your teaching can speak for itself, and that should reflect well in your scores and in your feedback.

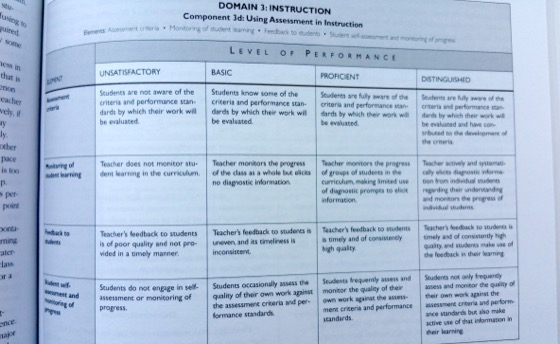

3. Worry About the Feedback, Not About the Score

Speaking of those scores, they really shouldn’t matter to you. I know that idea is easier said than done. However, if you’re interested in truly improving, the feedback should be your focus–no matter the evaluation model. In any situation, your evaluator should be documenting just about everything that happens during your teaching process. That documentation gives you the great opportunity to reflect on what you do and how you do it.

The Danielson Model is not about how well you score–it is about identifying the areas in which you can improve and defining and providing avenues for you to do so. If you are striving to score all 4s to get the best score possible, that is an admirable goal. But I think it is the wrong goal. Danielson said herself that “only angels” score all 4s. Instead of striving for perfection, spend time seeing how and where you can make your teaching better.

Art is a Natural Fit with the Danielson Model

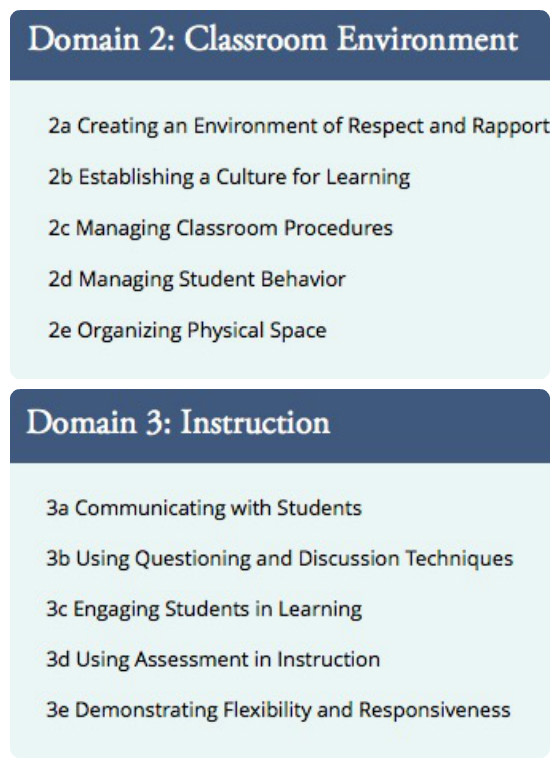

If you look at the Classroom Environment Domain and the Instruction Domain, what jumps out to you?

To me, the model is looking for EXACTLY what is happening in an art classroom. We provide an active, interactive, collaborative environment with high levels of student engagement and participation. We ask great questions, we assess, we monitor, and we give feedback. We are flexible with our lessons, we are responsive to students, and we have high expectations. Our evaluations are looking specifically at the things we do naturally as art teachers every day.

Even something as simple as an active Artsonia account for your school can be a huge part of the professional responsibilities domain in the Danielson Framework. It shows student progress, it communicates with and involves families, and it is part of a larger professional community of art teachers. That is just one example, but so much of what we do fits seamlessly into the four domains in the framework for teaching.

In the end, your everyday teaching practices set you up for success with the Danielson Model. Make sure, however, that your success is defined by how you can improve your teaching–not how that teaching might be evaluated. You really just need to do what is best for you and best for your students, and your teaching likely already does that. Don’t try to chase those scores; simply do what you do best as a teacher, and the numbers on your evaluation will reflect your skill and ability in the classroom while providing you opportunities for improvement. Which is exactly how an evaluation model should be used.

{image source}

Does your school use the Danielson Model? How has it worked for you?

What advice would you give for dealing with the Danielson Model or other evaluation models?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.