At the end of my sophomore year in college, the fate of my future rested in the hands of the faculty members at my school. I was to present samples of my work to them, and they would decide if I could continue being an art major. Dubbed “The Sophomore Review,” it was nerve-wracking, to say the least.

Logically, I’d told myself that I’d received good grades all year, and therefore would be fine.

But, when you’re standing in the hallway, awaiting news that will determine if you can continue with your future career plans, all logic seems to vanish.

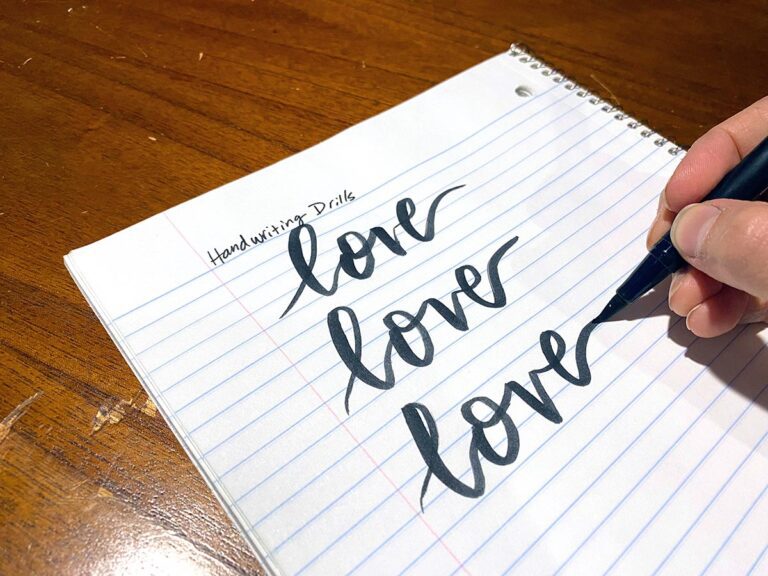

Once there, I remember little of what happened or what was said. But, I do remember one professor looking at my work and saying, “Your work has a messiness to it. It’s not resolved yet because you’re fighting your natural inclination to color outside of the lines. You’re doing what you think you’re supposed to do, trying to make things look pretty. Why don’t you try being you, embrace the mess, and see what happens?”

It took years for me to fully understand that message and how to apply it to my work.

However, those words freed me to explore, to stop being what I thought I was supposed to be and to start creating MY work.

When I became a teacher, I went back to those words as I thought about how to address craftsmanship in my art room.

As an art teacher, you may strive to teach your students to be neat. You might even grade on craftsmanship. As with most things in art, you also may define and deal with craftsmanship in a different way than I do.

When I discuss craftsmanship with my students, it’s not about perfection, or even staying within the lines; it’s about intention. If there are marks scribbled all over the page because the student wished to create a piece in minimum time with even less thought and effort, well then, yes, it shows. It’s a sloppy piece in every way possible.

But if a student is inspired by the work of Cy Twombly, and they’re exploring mark making, thinking about how beautiful a scribble, a mark, a spill, can be? Well then, by all means, I say go for it.

But what if it’s hard to tell? What if a student submits something and you’re not sure of their intention? Well, then you need to dig a little.

Let’s say a student submits a canvas smeared with red paint, telling me it’s abstract. I’d ask them to talk about what subject matter they abstracted to create the piece. If they tell me it’s non-objective, I’d ask them to discuss what elements and principles they used and how they worked to move the eye throughout the composition.

Student work is not about perfection, it’s about learning, exploring, and most of all, thinking.

When a student makes a mug with a crack in the bottom and a handle that falls off, one question to ask, is, “Is it even a mug anymore?” By asking students questions about the quality of their work, they quickly learn they can’t just put some scribbles on a paper and call it quits. At the same time, they learn there isn’t one way to have a piece that demonstrates, “craftsmanship.”

Telling our students how neat their work needs to be may come with the best intentions, but we need to be careful about the message it sends to our students.

If the ultimate goal is helping students become creative thinkers and develop a personal style, is neatness important above all else? Or, would we rather that students instead put their full effort into something to help them develop their personal style, even if it bucks traditional conventions?

In short, as with most things in art, perhaps craftsmanship is not as cut-and-dried as we want it to be.

If you have students who are looking for inspiration, here are 8 artists who colored outside the lines.

- Käthe Kollwitz

- Cy Twombly

- William Kentridge

- Willem De Kooning

- Alberto Giacometti

- Franz Kline

- Jean Michel Basquiat

- Sheila Hicks

Craftsmanship can and should look different for different projects. When you’re working to define craftsmanship, ask yourself, what are the learning objectives, and how does craftsmanship relate to those objectives?

How are you making space in your room for your student to learn the rules and then break them?

How do you define craftsmanship with your students?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.