Many art teachers have a lot of autonomy when it comes to curriculum. According to the 2019 State of Art Education Survey, just over 96% of art teachers stated they have “total control over what they teach,” or “follow a general framework, but have freedom in lesson planning.” While this level of freedom with curriculum planning sounds great in theory, it might not be producing the best result for your students. Curriculum planning requires a lot of decision making when you consider which concepts to teach, mediums to use, artists to introduce, and more. However, objective decision making free from your own biases of art and education can be difficult to achieve. But don’t worry, there is hope. Increased awareness of how your previous experiences and internalized beliefs and values may be influencing your decisions can help you plan a curriculum that better supports your students.

Below are a series of questions intended to help you uncover some of your own biases related to art education and consider how they may influence your curricular planning. Take time to think and reflect on each one. If possible, get feedback from a close colleague as it can be challenging to identify your own biases. This activity is not meant for blame or shame, but rather, to help you hold up a mirror to your practices for the betterment of your students.

What is bias and how does it live in the art room?

Bias is typically linked to stereotyping and groups of people, but the concept can also apply to arts education. Throughout your artistic life, you’ve developed positive and negative biases toward things like artistic styles, approaches, and artistic concepts based on your own experiences. Additionally, you have biases related to education and how students should respond in the classroom. All of which could be impacting your curricular decision-making.

How are your past experiences influencing your curriculum?

Every art teacher took a different path to get to the classroom. For example, some art teachers were star art students in high school, while other teachers never even took art until college. There are many different and successful paths to being an artist. As a result, many teach how they were taught. Because if it worked for you, then shouldn’t everyone follow? Not necessarily—as what worked for you might not work for all of your students today.

Take some time to think about how your current practices reflect those of your past teachers:

- How did you learn about art?

- What was your best art teacher like?

- Were all of your art teachers similar in their approaches to teaching art?

- Did you learn a variety of mediums or a few?

Carrying on some of the practices of those who came before you is not always a bad thing. Reflect on how much of your curriculum is driven by how you were taught and if you’ve fully considered and tried other art education methodologies. Also, be aware of any bias you might have toward philosophies or practices that vary from your own experience. Just as you can see from your art colleagues, multiple roads can lead you to the same place.

Who (or what) is represented in your curriculum?

All art teachers enjoy making and creating art and for good reason. Making art is fun, hands-on, and one of the primary reasons students enjoy taking art courses. There are, however, other aspects to art education that should be represented in a strong curriculum. More specifically, artistic language, art history, and exposure to the current art world.

Use the questions below to measure your level of comfort and knowledge with each of the following:

- Do you enjoy art history?

- What role do art history, knowledge of artists, and artistic vocabulary play in your course assessments or students’ grades?

- Is there a particular period in art history you prefer?

- How would you describe your knowledge of current and contemporary artists?

- What value do you place on students knowing and using artistic vocabulary in the studio?

Your artistic preference is not the only thing that can influence your curriculum. Sometimes your own discomfort or lack of expertise is enough to unintentionally keep specific content out of the classroom. But is that always best for students? Use this time of reflection to be honest about what is missing from your curriculum because you aren’t comfortable with the material and develop a plan to refresh yourself with that content.

What are your artistic biases?

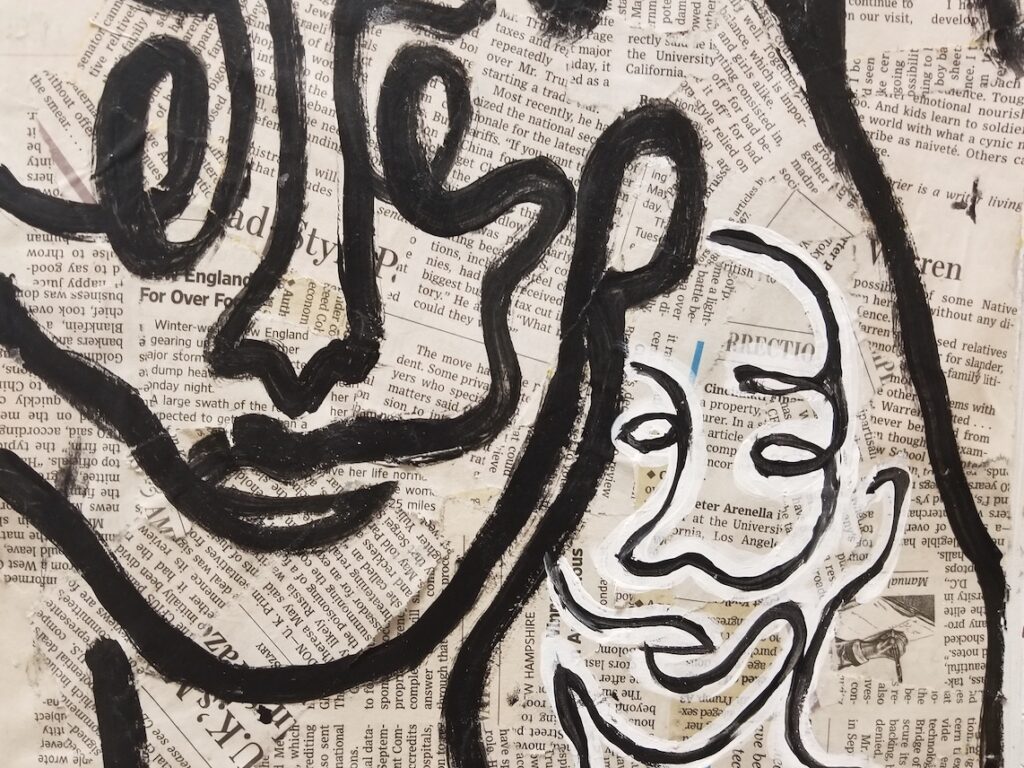

As an artist, you value certain styles or aesthetics over others. For example, are you more engaged by pieces with looser or tighter mark-making? Do you prefer viewing more abstract or realistic work? Think about how your artistic preferences can drive your curriculum. Ultimately, you want to expose students to a variety of artistic styles and approaches to meet the diverse interests in your art room and not only the ones you prefer.

Here are some questions to help you reflect on your preferences as an artist:

- What mediums do you like?

- What styles or aesthetics in art do you like?

- How do you define art?

- How would you describe your personal art?

- Which artists or art teachers do you follow?

Now, take it back to your classroom and connect your reflections to your projects. Do the projects you assign favor your own preferred style? How similar is student work to your personal artwork? And, do you teach any project you wouldn’t want to do yourself? Be sure what you value isn’t being pushed on students and that you’re allowing them to explore mediums and styles to develop their own preferences.

What biases do you have with instruction in the art room?

In many educational conversations, curriculum and instruction are treated as separate entities. But when you’re responsible for both, they are more intertwined. For example, if you value control in the artistic process, your curriculum might be structured to minimize student choice. Once you have a better understanding of your own instructional values, you can identify potential areas that could be influencing your curriculum.

Start by reflecting on the questions below:

- What value do you place on technical skills versus creative skills?

- What value do you place on having control in the outcome of the student projects?

- What value do you place on organization in the classroom?

- How important is it to you that students are happy with their finished piece?

- How do you define student success with an art piece?

- What do you expect from a beginning versus an advanced art student?

In a studio with diverse learners, each of your students will be successful with different approaches. Some students will thrive under a more controlled setting, and others will feel constricted and need a more flexible structure. You can help every student succeed by exposing them to a variety of curricular structures, even those that challenge your personal preference. Be sure your curriculum is not reflecting what you prefer as a student, but rather what they need to be successful.

How to move forward?

As an art teacher, you have the responsibility of providing students with a relevant and engaging curriculum. Students deserve a meaningful experience and the opportunity to develop skills in the art room. But even when you have the best of intentions, some of your curricular decisions can be driven by your own experiences and preferences rather than student needs. Being more aware of your biases and how they may plan a role in your decision-making is the first step to being better for your students.

What other biases can impact the curriculum for students?

Why is it so difficult to acknowledge and accept personal biases?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.