Have you ever heard the idiom “publish or perish” and immediately felt daunted? The phrase is typical in the world of higher education and implies that your career as a scholar will wither away if you don’t publish your research. Or you are not an expert in the content area you teach. Despite the dramatic implications of “publish or perish,” try not to let the phrase intimidate you. The expression is usually used to indicate the importance of publishing.

The National Science Board estimates that millions of research articles and texts are published and shared around the globe every year. This is done to further what we know about best practices in a variety of fields. A research article is a peer-reviewed article that explains the research performed.

A research article typically includes the following:

- A problem that looks at areas in the art education field that need improvement

- A research question that seeks to answer the problem

- A research statement that identifies the purpose of your investigation and how you will conduct it

- A literature review that summarizes and brings together all the research already published about your problem

- Your methodology or the strategies you will use to investigate your research problem and answer your research question

- Data are the pieces of evidence you collect from the participants of your research investigation. This can include interviews, surveys, observations, test scores, art sketches, critique panels, focus group discussions, and more.

- A data analysis of the data you collected using a specific approach

- Correlated implications that take your data results and apply them to infer conclusions on the problem at hand or in future studies

As an artist and artist-teacher-researcher, it’s important to add your unique expertise to the body of research out there. Publishing your work is also a way to continue pushing your professional practice and stay reflective. Additionally, you may be able to earn certification renewal credits for publishing the action research you are already doing in your classroom. Publishing your research would both enlighten people’s understanding of the arts and open up a variety of career options. This would include academic consulting, college and university professorships, worldwide collaborations, entrepreneurial aspirations, and more.

Here are five helpful steps if you are interested in publishing your findings or advancing your career in the arts. Let’s begin to unravel the “publish or perish” narrative!

1. Explore research journals.

A great starting place is to investigate different journals and choose where you will want to submit. Consider your overall research goals when choosing where to submit for publication. You will want to submit to a publisher that shares your interests, mission, and philosophical outlook. Also, think about the overall hierarchy of the research world and publication types. Yes—there is a hierarchy. There are different types of publications in the academic publishing world. The publication types are ranked according to their scholarly impact.

What is the hierarchy of academic publishing?

- Authored articles in top-tier journals, such as peer-reviewed journals and ones with a high journal impact factor (JIF).

Example: Harvard Education Review and the American Educational Research Association (AERA) - Authored books of highly ranked publishers.

- Authored articles in other peer-reviewed journals.

Example: National Art Education Association (NAEA) or the Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy - Edited books.

- Authored book chapters.

- Authored book reviews.

- Presented at conference proceedings with conferences that have an online paper repository.

Despite the hierarchy in the academic publishing world, there are still advantages to participating in numbers five through seven. You still disseminate your research to your peers in the academic community. This gets your ideas out there, looks good to potential employers and partners, and establishes your publication imprint. Some additional journals to explore are the European Educational Research Association (EERA), The Qualitative Report, Art Education, or the International Journal of Education and the Arts.

2. Start writing.

When considering how to break into the publication world, think first about what you are going to write about. Whether you previously conducted a research investigation for a course, capstone project, or independent study, research that you have already started and are passionate about is a good place to start. Maybe you have always been interested in the effectiveness of a Choice-Based curriculum, strategic uses of assessments in the art class, or using visual journals to increase original idea formation. Focusing on a topic you are passionate about will fuel your motivation to get the writing done well and on time.

Chunk your ideas.

Once you have your idea in mind, break it down. Just like you do in lesson plans for students, chunking ideas can make a steep task more manageable. It can also help you focus and keep on track with deadlines. It can help you to be more thorough in your research as well as stay organized.

Here are three ways you can chunk your ideas:

- Break down your work.

Extracting subtopics from your bigger work can potentially create four to five new articles. For example, your literature review could be an article in itself. Then, your methodology could be another article, and so on and so forth. - Branch out from your original research.

Did your research lead you to new discoveries or unanswered questions? Push that towards a passion project spin-off. - Attend research conferences.

Conferences (art education or general education) such as NAEA or AERA are great places to meet scholars with similar research interests. You may find someone you would want to publish with! Collaborative publications are popular and applauded by the academy. Also, finding a writing partner lessens the workload and provides you with new perspectives.

3. Ask for feedback.

Make sure to get feedback on your work as you are writing and when you are ready to submit. This can be from a variety of people that you know, like your friends, family members, and colleagues. Once you have a group of people who are willing to look over your work, you need to know what they should be looking for.

Below is a helpful checklist that can guide feedback on your manuscript. You can provide this to others use it yourself to check your own work before submission!

- Is my research ethical?

- Does the title make sense?

- Is my argument clear throughout?

- Have I arranged my topics and subtopics in a sound and logical manner?

- Does my evidence support the literature?

- Does my manuscript have too much or too little jargon?

- Is my topic original and interesting?

- Have I formatted my manuscript according to the journal’s requirements?

4. Submit your work.

After you have written a research paper on your topic, the next step is to submit and publish your findings. Once you have identified where you want to submit your work for publication, get familiar with the publisher’s focus and requirements. Pay close attention to how they want you to format your work. Formatting your work improperly is an easy way to get your manuscript rejected before they even read it.

Sometimes, the peer-review process can be timely. Other times, the journals can take months before responding to your submission. Submitting to more than one journal at a time can be tempting, but you just have to wait it out. Most journals will not allow your work if they know it is also being published somewhere else. This is considered unethical, and it is highly frowned upon in the industry.

After you submitted your manuscript and the peer review process is complete, the journal will respond to you with one of these responses:

- Accepted with no revisions.

- Accepted after minor or major revisions.

- Rejected.

It is customary to be asked to revise a manuscript. It is also customary to be rejected altogether. If you encounter either, know that you are not alone. Consider the revisions that you are asked to make or go to another publisher that aligns more with your style and work. Just keep trying!

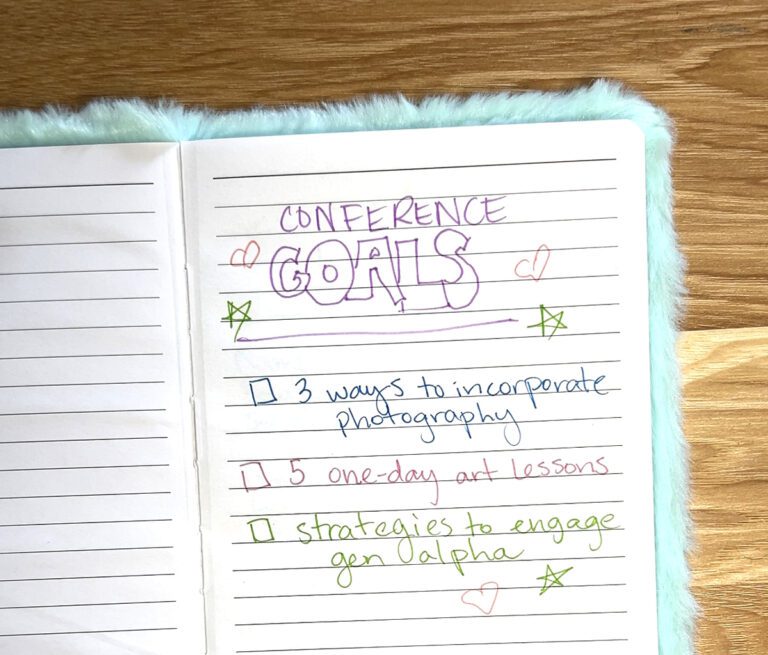

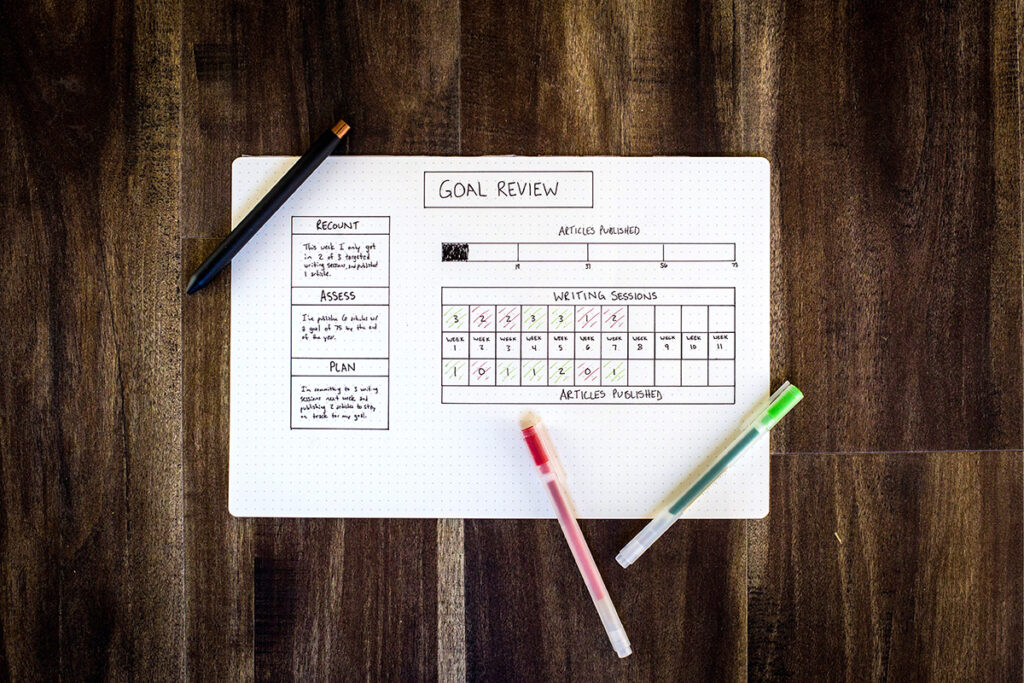

5. Set your publication agenda.

After your work has been accepted by a journal, set a publication goal for yourself. Having a publication goal will assist you in staying on target for the year.

When creating your goal, keep in mind the following questions:

- What type of impact do you want to have on the research community?

- What types of publications will help you advance your career?

- How many publications will you commit to doing each year?

Getting your first manuscript accepted will give you a better idea of what you need to get more acceptances in your topic area. Chunk your original unpublished works to get five or six more publications. Think about using new findings in your previously published articles as kick-starters for future publication ideas.

Noteworthy publishing expert Kevin Kumashiro suggests that you should aim for two to three publications per year.

Leave your mark!

Apply the three helpful steps above to start your publication legacy in the art education field. Use research that you already have as your writing launchpad. Submit to publishers that share your philosophical aims and scopes as an artist and artist-teacher-researcher. Set annual publication goals and stick to them. Lastly, do not let the “publish or perish” idiom shake your publication destiny. Just remember the mission of your teaching and writing. Stay committed to shining your research light!

For even more tips on publishing your work, check out the following resources:

- How to Get Your Research Published

- An Inside Look at Publishing (Ep. 239)

- The Art of Writing: Why Writing Matters in Art Education

Have you ever published your work or research in a journal?

What tips do you have about the publication process?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.