Whether new or seasoned, you are probably well aware that unpacking the International Baccalaureate (IB) Visual Arts curriculum guide takes time to digest. The slur of new terms, matrixes, Venn diagrams, and acronyms can feel mind-boggling. Take a deep breath—you are not alone. The adjustment is often messy, sticky, and overwhelming. The open-ended course structure may seem intimidating at first but will eventually feel liberating.

At its heart, IB Visual Arts offers an avenue for students to deeply experiment with artmaking processes, explore and make connections to the world of artists, and create contextual, conceptual, and personally meaningful works of art.

The International Baccalaureate Diploma Program (IBDP) delivers a challenging curriculum for globally-minded students worldwide. Visual Arts is an elective course within the curriculum. From private to public schools, this externally-assessed curriculum will challenge your students and offer valuable tools for lifelong engagement in the visual arts. In addition, students may receive college credit due to their exam scores.

Unpack these five points of discovery as you teach IB Visual Arts.

1. Pace your curriculum over two years.

IB was designed to be delivered to students during their last two years of high school. While two years may seem lengthy, there is a lot of ground to cover! As you set up your course, consider what your students need to do by the end of those two years, and work backward from there. Drafting a pacing guide will help you meet the curricular goals more effectively. In addition, some schools offer informal or formal “pre-IB” courses, while others cram IB Art into a single year for graduating seniors. Depending on the experience levels of your incoming Visual Arts students, you may need to differentiate and build in extra time to cover advanced artmaking techniques at the start of the first year.

One timing guideline to keep in mind is that the Visual Arts curriculum wraps up in the spring of an IB student’s last year. Second-year student work is submitted in April for the May examination process in the Northern Hemisphere. Log into the IB portal or speak with your IB Coordinator for the most up-to-date information and deadlines.

The IB Visual Arts guide spells out different criteria for each assessment task over several pages. Familiarize yourself with the criteria, and make a one-page rubric for each assessment task to help your students understand what’s required to succeed.

2. Understand the IB student levels.

IB offers students the choice to enroll in the Diploma Program or take courses as standalone subjects. Those who register in IBDP take six subjects, of which Visual Arts is an elective. However, many students decide to take IB Visual Arts as an advanced art elective. In theory, any student can take IB Visual Arts without prior art knowledge, but this will depend upon your school and your school’s policies.

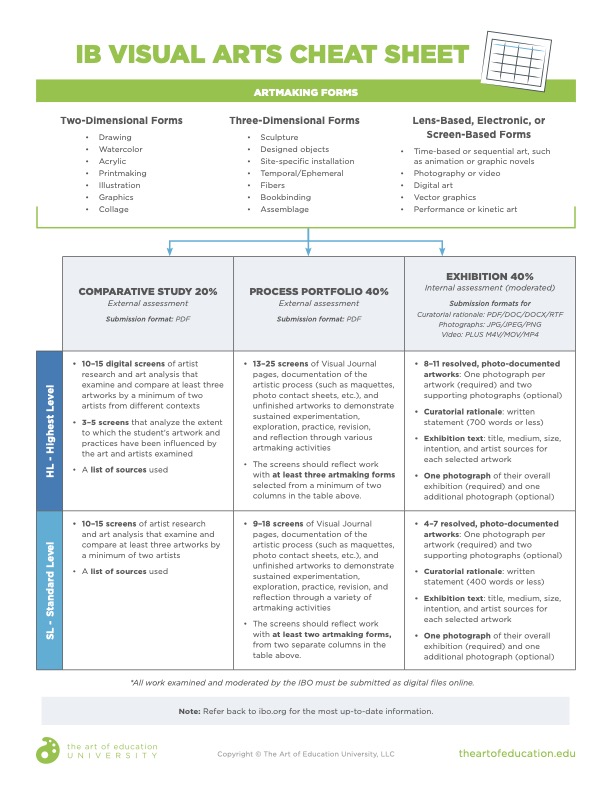

When students enroll in the course, they sign up for a Standard Level (SL) or Higher Level (HL) course. What’s the difference? Primarily, each level requires a different amount of work and engagement quality, but they also impact a student’s ability to obtain their IB Diploma. To better understand the two levels, it’s worth viewing a snapshot of the assessment tasks. Grab this download for an at-a-glance look at IB Visual Arts and the requirements for each assessment.

3. Prepare to deliver three assessment tasks.

When I began teaching IB, my new Visual Arts students were apprehensive about the workload. They struggled to envision ideas, and they battled to think critically and self-reflect. Yet, they were also excited by the challenge of creating a self-directed, public exhibition! Harness this seed of motivation as you guide your students through the assessment tasks. As outlined in the 2014 Visual Arts Guide, the tasks are the Comparative Study, Process Portfolio, and Exhibition.

The IB organization splits the tasks into Internal Assessments (IA) and External Assessments (EA). The examining committee views both assessment types, but the IA is moderated based on individual teachers’ comments, while the EA is examined without teacher input. Each assessment is also valued differently.

Here is quick a breakdown of the three tasks:

- Comparative Study (EA, worth 20%)

The Comparative Study is an investigation into the artworks of others from varying contexts. It includes a student-driven analysis and comparison of how, when, and why artists produced their works. HL students also show the study’s impact on their artmaking practice. - Process Portfolio (EA, worth 40%)

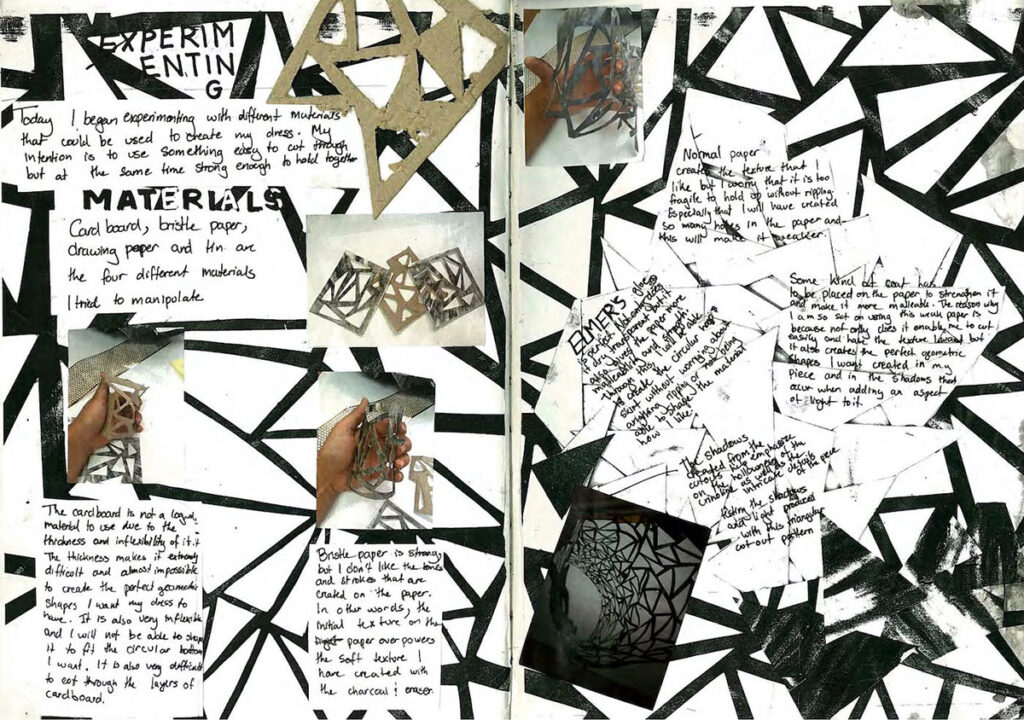

The Process Portfolio is a digital collection of evidence that demonstrates conceptual brainstorms, skill development, experimentation with diverse media, an investigation into artists, and reflection. The Portfolio evidence can include pieces from a sketchbook, digital documentation, maquettes, or large-scale experiments. HL students must study a wider variety of artmaking forms and submit more evidence than their SL counterparts. - Exhibition (IA, worth 40%)

At the culmination of the course, students select a series of resolved artworks made with various media to curate a cohesive exhibition. The Exhibition is digitally documented and supported with Exhibition Text and a Curatorial Rationale. This written statement connects the exhibit’s themes, concepts, influences, materials, techniques, and aesthetic choices. HL students are evaluated more stringently for their curatorial decisions, and they present more artworks than SL students.

4. Teach a holistic curriculum.

Yes, you can teach IB Visual Arts methodically to ensure you check everything off the assessment checklist, but the outcome will feel dry and dogmatic. When teachers plow through their checklists, they can cheat students from exploring the intertwining transdisciplinary and real-world connections that inform the artistic process. The curriculum will be more meaningful when you highlight the creative intersections between other subjects, artistic practices, and assessment activities.

The IB organization sets forth with a critical goal “to develop internationally minded people who, recognizing their common humanity and shared guardianship of the planet, help to create a better and more peaceful world.” The program develops the whole person while urging students to look beyond themselves to develop a critical worldview when approaching their studies. The IB core curriculum includes three overlapping elements called the Extended Essay (EE), Creativity-Action-Service (CAS), and Theory of Knowledge (TOK). All of these elements provide dynamic intersections with student interests, their six chosen subjects, and real-world applications.

When you guide students through this curriculum, you may discover gaps in your knowledge of artists, materials, and concepts. At times, the many tangents running through your classroom may feel messy and unwieldy. However, when the holistic potential of the curriculum becomes central to your classroom, you have the opportunity to offer meaningful feedback and become a guide for your students as they navigate the complexities of visual arts.

5. Break down the curriculum with further reading and connections.

As one of a few IB Visual Arts teachers in South Africa, I initially felt siloed within my region’s art curriculum as the sole art teacher within my school. You, too, will have to cast your net to build a tribe of IB peers! Meanwhile, discovering practical resources may be one of the easiest ways to firm up your knowledge of the IB curriculum.

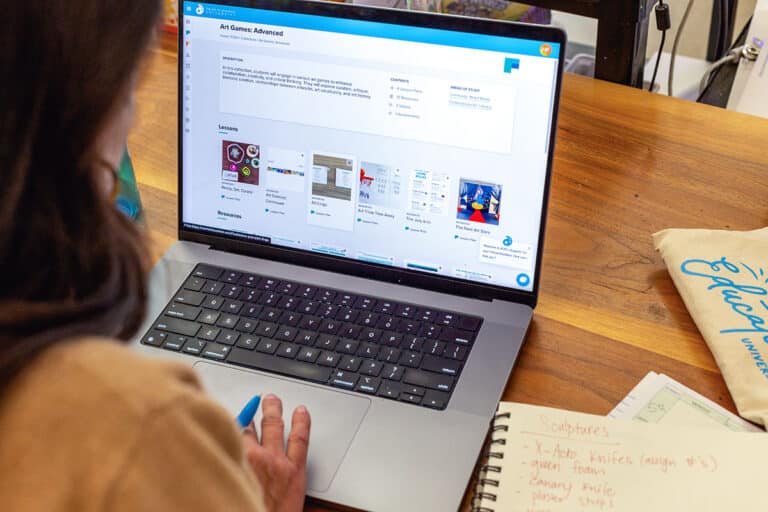

Two notable books offer practical insight into the curriculum. In 2017, McReynolds, who also authors content with InThinking and provides IB teacher training, wrote Visual Arts for the IB Diploma Coursebook. Current and former lead examiners Vaughan, Poppy, & Paterson coauthored IB Visual Arts Course Book: Oxford IB Diploma Programme the same year. Both texts break down the course criteria, share student examples, and offer advice to deliver the curriculum, create purposeful units, and support independent student growth.

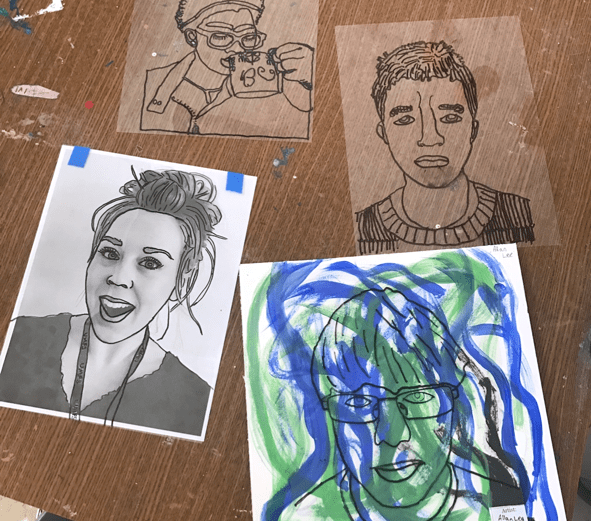

Articles about Advanced Placement (AP) and strategies that advance student thinking can also provide meaningful overlaps with the IB Visual Arts curriculum. Check out 8 Ways to Use Clichés to Support Deeper Thinking and A Portrait Lesson You Won’t Want to Miss That Synthesizes Media for more ideas.

Here are some final words of wisdom.

Encourage autonomy and support your students’ independence. Your students will need research skills and self-motivation to take a personalized approach in this course. Because student experiences in IB Visual Arts will move in several directions, your classroom will buzz with student choice. You may have students working with thirty different combinations of materials, themes, and concepts at any one time. It may sound daunting, especially as you consider providing feedback and keeping tabs on your students’ progress!

At its best, IB Visual Arts allows for a meaningful experience for teachers and students alike. There is no “one way” to structure the curriculum or create artwork within IB Visual Arts. While this flexibility can seem intimidating, it’s fertile terrain for a creative investigation of the subject. My first year teaching IB Visual Arts was a blurry series of trial and error coupled with squeals of joy and sparks of connection.

Trust me—if you roll up your sleeves with a can-do attitude and prepare for some intense learning, the effort will be worth it! Without a doubt, by embracing the positives of this curricular model, your students will develop grit, curiosity, and a lifelong interest in the arts. When you remain open to the nature of the course, you will be astonished by the creative potential of this framework.

How do you use visual journals to support students’ experimentation and art analysis throughout the two-year curriculum?

How are you already integrating holistic learning experiences in your classroom?

What questions do you still have about IB Visual Arts?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.