Picture this scenario: You introduce a new unit and reveal an art history topic to your students. After you outline a short artist-research project, your students visit their local library and check out quality source materials. They navigate the internet with ease and inquire further into unfamiliar concepts. Finally, your students identify relevant images and text to support their topic. Their presentation includes a list of sources on the final slide.

Sounds like a pipe dream, right?

In reality, our students need scaffolded instruction to improve their research abilities.

Consider that worldwide, people conduct over 3.5 billion Google searches daily, totaling 1.2 trillion searches yearly. Over 300 hours of video footage are uploaded to YouTube every minute, and 4.2 billion “likes” are clicked on Instagram each day. We live in an age where anyone can publish online, and media permeates our world.

How can we guide our students through the process of navigating media with purpose?

When you teach artist research in your art classroom, you prepare your students for real-world applications using several 21st-century skills.

Research is holistically baked into many artmaking processes. Developing and articulating connections to the work of other artists is a core part of Responding in the National Core Art Standards. Whether you teach advanced students through AP or IB Visual Arts or strive to support your elementary or middle schoolers, students will need your support to research efficiently and effectively.

Let’s establish and unpack twelve essential understandings for developing good research habits.

1. Define “information literacy” for artist research.

Budding art student researchers need to understand when to look beyond what they know. According to the American Library Association, information literacy is a composite set of skills that enable individuals to “recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information.” To be information literate, students need research skills and critical thinking skills. Additionally, we can prepare ourselves to support a broad range of competencies.

2. Develop good research habits through repetition.

To instill good research habits in your students, provide them with routine opportunities for research. You can spiral these activities by starting small and building up to more complex tasks. Exposing students to the work of other artists often and asking them to do a little digging for small tasks will help them develop the necessary autonomy for more extensive research projects.

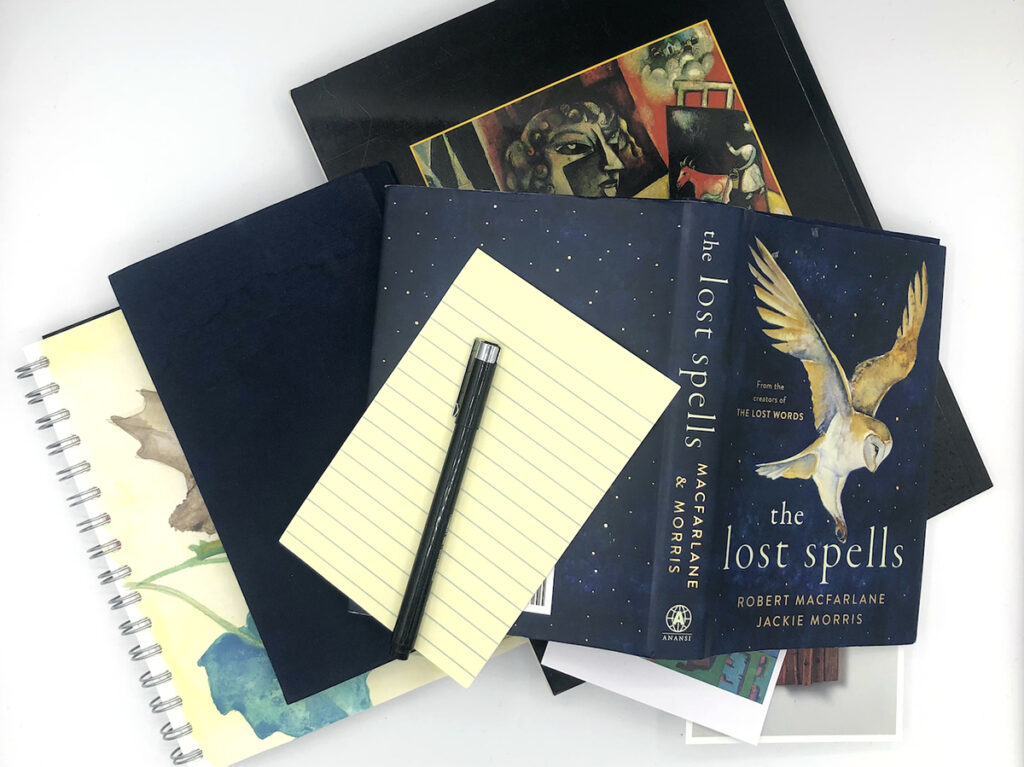

3. Foster a renewed relationship between students and the library.

At the start of the school year, I find it helpful to take my students on a field trip through the hallways to our underutilized library. Upon entering the library, you can start a foundational conversation about sources. Engage your media specialist or librarian in advance to collect some of the best art books to share. Check your students’ knowledge of books, from the publication page and the table of contents to section headers and the index.

4. Discuss the concept of “quality” resources with your students.

As your students flip through the glossy book pages, the conversation about quality and authentic sources begins. Yes, the internet is full of options and ideas. However, your students may be surprised to learn about the quality control processes required for professionally published books. After learning about quality sources, it’s time to discuss digital wayfinding.

A straightforward search on Google, Bing, or Yahoo will provide a list of sources and topics. Image searches are often more exciting for students at the start of a quest for new inspiration. It is good to remind them that image searches work better as a starting point for research than as the only line of inquiry.

5. Enhance internet search results with better keywords.

Shane Mac Donnchaidh offers several options for refining internet searches to improve the results. First, students will find enhanced results by looking at quality sources through a basic internet search—not an image search.

More specific phrases will enable a more precise outcome. For example, the most popular images and articles will appear when looking up historic Swedish artist Hilma af Klint. Ask your students what they want to know about new artists as they embark upon their research. They will discover that phrases such as “Hilma af Klint sketchbook” or “Hilma af Klint works on paper” will yield more specific results. Depending on your students’ ages and experience levels, they may need support with this. A prepared menu of search terms, quick tips, and questions can help lead students through a more successful research experience.

6. Identify domain name endings for quality results.

It may sound like a no-brainer, but many of your students may not consider the domain name ending as a key for finding enhanced results and identifying credible sources.

Discuss the difference between typical endings, such as:

- .com denotes a commercial website.

- .org traditionally means the website is for a nonprofit.

- .gov is a government website.

- .edu represents an educational institution.

To narrow their search, students will need to type “site” followed by a colon and the desired domain ending. For example, “Land Art site:.org” will narrow a search into nonprofits such as museums or research organizations. This trick is one quick and easy way to zone in on quality sources.

7. Apply critical thinking skills to determine the relevance of new information.

Work with your students to identify parameters for identifying “reliable” or “quality” sources. Is the information on the site up-to-date? Does the data come from a reliable source? How do they know? Is the information on the topic detailed? Does each source offer something different from the previous source? Pose these questions in a visible place for students to consider as they continue their research in books, magazines, and online.

8. Implement a reverse image search to authenticate questionable artworks.

Have you ever found yourself fooled and unsure whether something is original or an imitation? It is often easy to detect an outlier with a trained eye. Our students often don’t have a discerning eye or knowledge of art history to tell the difference.

Reverse image search tools, like TinEye, allow you to drag and drop a screenshot or image file into their search engine. If an image is authentic, the search results will include art museums, galleries, exhibition reviews, or artists’ websites.

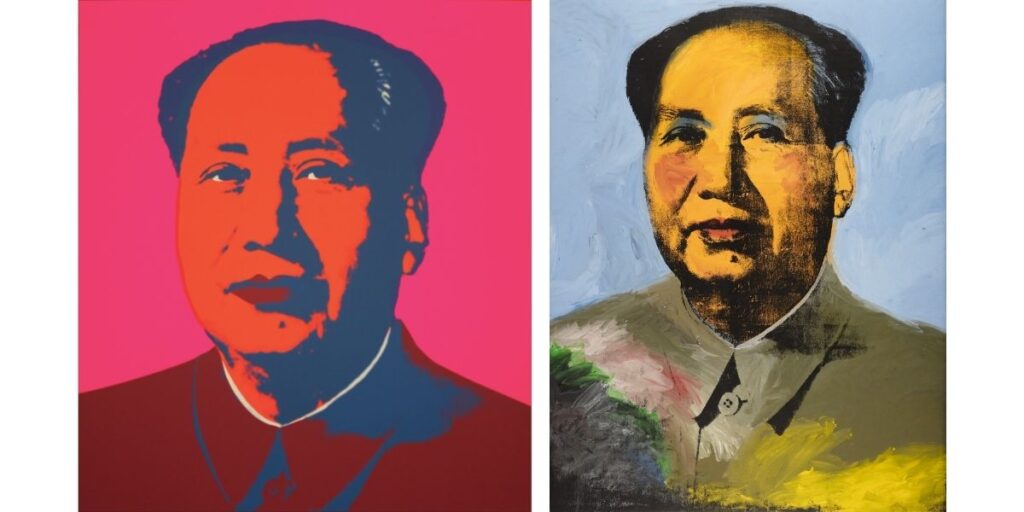

The examples below show two versions of Andy Warhol’s Mao Zedong. Which one is by Warhol? Play with TinEye and see if you can figure it out!

9. Suggest a minimum number of sources and keep a running list of sources handy.

Three sources will help build a well-researched and balanced report, article, or presentation. While three sources may seem like a lot for a younger student at first, they will quickly catch on to the advantages of considering multiple points of view.

Your students may need additional training to stay organized. Learning how to bookmark and organize websites is one way to manage a list of sources. You can also teach your students to keep a single document with linked references for easy access. Online bibliography generators, like easybib.com or zbib.org, help students maintain a digital record of sources. Students enrolled in IB Visual Arts will appreciate this practice when preparing their Comparative Study assessments.

10. Teach your students about primary sources through experiential learning.

It’s unnecessary to explain to art teachers how incredible it is to see art in the flesh! However, many students don’t experience art beyond the art classroom. Organizing an external field trip requires preplanning, administrative approval, and guardian permission. And it is always worth it. When students encounter work first-hand, they understand the difference between that and experiencing work online or in a book.

When field trips are not possible, share your own in-person experiences with your students. Then, encourage your students to visit local galleries and nearby fine art museums or check out museum offerings during their school holidays. Museum visits may inspire new artworks, IB Comparative Study proposals, or even IB Extended Essay ideas for advanced students. This experiential approach to art research can extend into a lifelong interest for students of all ages.

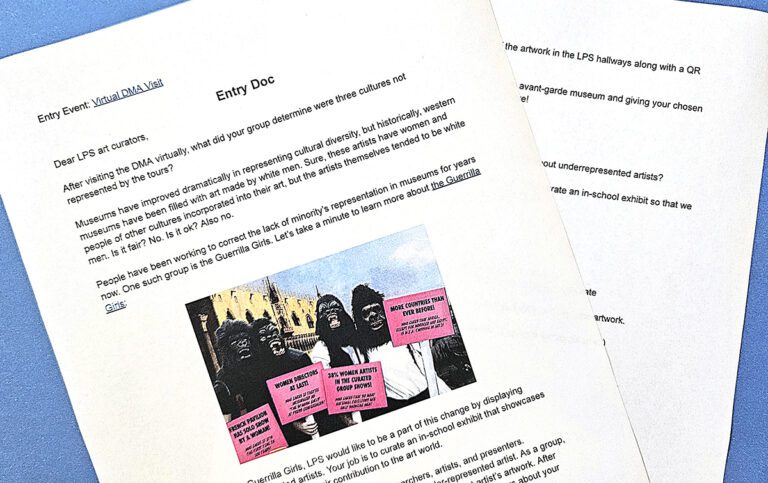

11. Create a virtual museum field trip.

Your students can attend a dozen different virtual museums in a single day—an impossibility within the physical realm! Virtual offerings have increased and improved in recent years. Virtual field trips are easy to organize, and they retain many of the qualities of visiting a museum. These experiences also support student autonomy and choice.

Here are some top virtual museum sites and resources to consider:

- The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

- Amaze Your Students With Google Arts and Culture

- The British Museum’s Museum of the World

- 10 Museums With Virtual Tours (Including the Louvre, Uffizi, and the MOMA.)

12. Curate a list of artists by theme, subject matter, media, historical movements, or geographic location.

If you give students absolute freedom to peruse the internet searching for new artists, prepare for uneven outcomes. Students often don’t know where to look, and they quickly become entangled in a wayward search with few results.

Instead, curate a list of artists relevant to a specific unit or activity. With a shorter list of options, your students will be more efficient in selecting a research focus. Lists allow students more time to engage with the critical thinking processes required in research.

If you are looking for artists to share, here are some curated resources to get you going:

- Art21 Artist List

Students can search by theme or medium with drop-down menus. - Art Through Time: A Global View

This website is organized by theme. - Smarthistory

This website is organized by date. - Rethinking Art—13 Artists Who Play With Form and Function

- 11 Fascinating Artists Inspired by Science

- 7 Contemporary Artists to Support Advanced Students

- 6 Latinx Artists Your Students Will Love

Developing good research habits does not happen overnight.

Try taking one or two of these ideas to implement at first. Then, add new ideas and habits along the way. When you scaffold research skills, you will see increased student engagement in the research process. Once your students have the skills required for research, they can focus on deeper concepts. Interpreting art and creating comparative analyses provide excellent avenues for critical thinking. However, you do need to develop student ownership to get there. You can do that by developing student autonomy through the acquisition of research skills using the twelve tips above.

National Core Arts Standards (2015) National Coalition for Core Arts Standards. Rights Administered by the State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education. Dover, DE, www.nationalartsstandards.org all rights reserved.

NCAS does not endorse or promote any goods or services offered by the Art of Education University.

How do you currently help students develop their research skills?

How can you incorporate routine research into your curriculum?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.