A trifecta of technology, social media, and virtual learning has fostered a dynamic where students are afraid of face-to-face tension. Students are getting used to in-person interactions and relationships again. There can be a learning curve when reacclimating to anything. In the art room, we often see students struggling to speak and listen in simple class discussions or more intense artwork critiques. How do we get students comfortable with sharing honest feedback with and to their peers?

Let’s explore four scenarios to show how you can build up to an art studio where honest feedback, constructive criticism, and challenging topics are not only expected but valued.

Before diving into the scenarios, let’s look at a few practical overarching tips you can start with and strive toward. The tips below start simple and foundational and become more challenging as you move further down the list.

Here are helpful tips to guide your planning:

- Build in lots of opportunities for in-person small talk and conversation to grow class connections. Try cheesy team-building exercises, reading warm-up answers out loud, or sharing weekend highs and lows with the class. The prioritization and nurturing of relationships are key to tackling difficult topics.

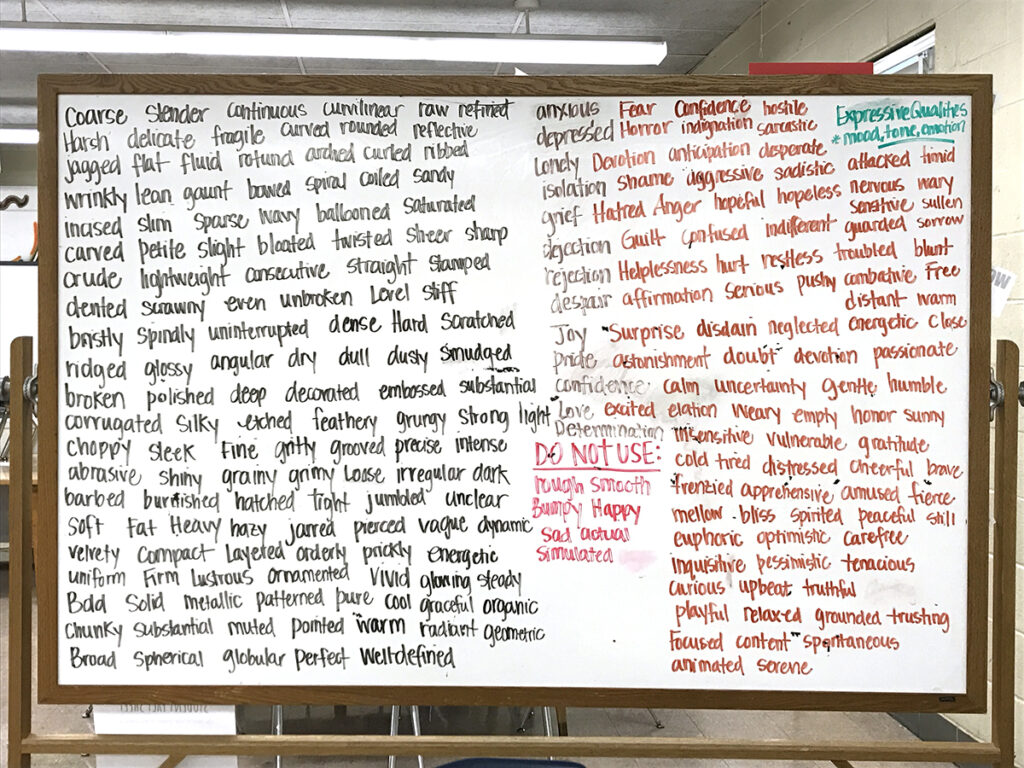

- Keep feedback tied to a rubric or set of criteria, such as a list of words related to the elements and principles of art. Post the prompts given later in this article to guide each student’s statement and response.

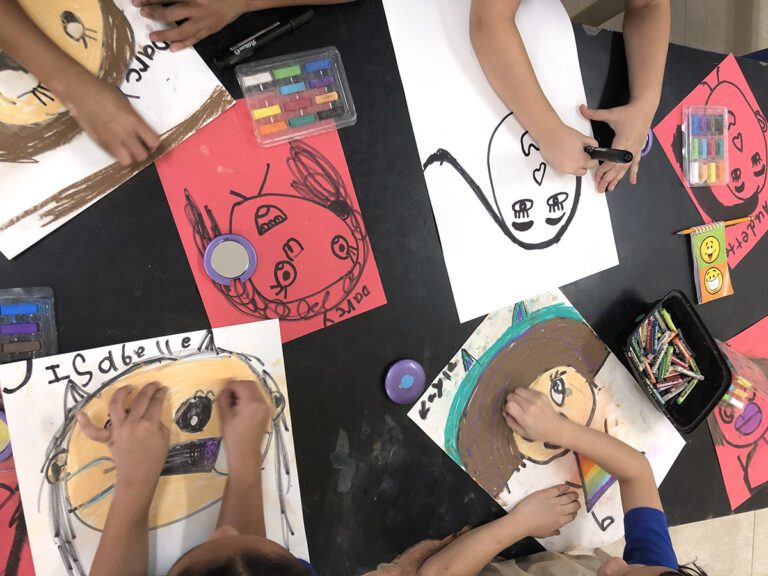

- Start with a physical reproduction and critique a famous artwork. It’s easier when the artist isn’t in the room!

- Have the students critique one of your artworks. You can model how to respond to feedback, including feedback you don’t agree with.

- Anonymously critique a peer’s work by typing responses and using emojis to assist in providing a clear and kind tone. Students can randomly read the responses aloud or try this sticky note method.

- Divide the class into smaller groups for more meaningful feedback and a more intimate, private setting.

Here are four scenarios to illustrate how to build students’ resiliency to tension and face constructive feedback confidently.

Just like the list of tips above, the following scenarios are organized by intensity and are loosely based on George Bateson and Robert Dilts’s Logical Levels. Logical Levels is a hierarchy that captures how human behavior, identity, and communication intertwine. For the purpose of this article, we will start out with more common examples and work our way up to more serious conversations you may have in your secondary art room. Ensure you adhere to your district and school policies regarding challenging and sensitive topics. Remember, when the conversations get more difficult, there is more opportunity for students to step up, learn, and grow!

Scenario 1: Barrier

The Situation

Let’s say you are having a progress critique, and students post their artwork on the wall. You have a student who is in a wheelchair. They can’t easily navigate around the students to view the artwork over their standing peers’ heads. This is a barrier.

Why It Feels Tense

If the barrier is not addressed ahead of time during your lesson planning and prep, the student in the wheelchair may feel isolated and uncomfortable. They may want to do well but may not be able to participate.

Options for Leaning In

You make adjustments prior to the lesson so this student can view the work comfortably and participate. You instruct students to hang their work slightly lower on the walls and have all students bring over a chair to sit on while they view the work. Everyone makes accommodations, and the class dynamic and assignment can continue without anyone feeling singled out or hurt.

For more tips on how to approach your instruction with an inclusive lens, read this article.

Scenario 2: Preference

The Situation

Here’s another fairly simple example. Your students are listening to music while drawing during independent studio time. A student is streaming their favorite country musician. Another student leans over to them and blurts out, “That song is terrible! How can you listen to that?!” You observe the first student getting defensive and tense. What just happened?

Why It Feels Tense

“You” language is often taken as blaming and attacking. Introduce, model, and reinforce “I” language versus “You” language in the art room. In our music example above, the student could still express their opinion by saying, “I don’t like country music. I like hip-hop!”

Imagine one student saying to another, “I don’t like all of the red in your artwork.” While this student is applying “I” language, this may be a more sensitive situation because it’s about another student’s creation. Our students often pour their hearts and souls into their masterpieces, so when negative comments roll in, it can feel like a personal slight.

Options for Leaning In

Here are some ways to apply “I” language in the art room during a critique or art analysis:

- I see…

I see a lot of red. - I don’t see…

I don’t see a lot of variation in colors. - I like…

I like the bold color. - I don’t like…

I don’t like the amount of red. - I wonder…

I wonder why you used so much red. - I’m curious as to why…

I’m curious as to why you used so much red. - I think…

I think there is a lot of red in this artwork. - I believe… because…

I believe there is too much red in this artwork because it hides the focal point. - I want to share…

I want to share Barnett’s Newman’s Vir Heroicus Sublimis. This artist used a ton of the color red but broke it up with lines he calls “zips” to make it visually interesting.

Ask the students to consider if the things their peers observed about their work align with their intent. It’s a way to know they are communicating their idea clearly, and it is one indicator to determine how successful or strong their artwork is.

Close the loop by encouraging students to smile and say, “Thank you.” It’s harder to be mad when someone is giving you a caring smile. Remind students that honest responses can be difficult but good to hear. They can point out where your artwork can grow and get better! Model how to graciously thank and validate feedback regardless of if you agree or disagree. This will reinforce and welcome a culture of honest feedback moving forward.

Here are some ways to say “thank you:”

- Thank you!

- Thanks for sharing.

- I appreciate hearing that.

- Thanks for pointing that out.

- Great observation!

Bolster spirits by ending each critique with a round of applause or snaps for all who participated!

Play this game with your students!

Modeled after the video series, Spectrum, by Jubilee, this is a fun game that incorporates movement and helps students express their opinions using “I” language. This game does require quite a bit of room to spread out. If you do not have a big classroom, you may need to borrow the gym or go outside.

Here’s how to play:

- Mark seven lines on the floor with string or tape or have students stand behind marked chairs.

- Each line will signify the following: strongly disagree, disagree, somewhat disagree, center base, somewhat agree, agree, and strongly agree.

- Read a statement. Make it lighthearted and silly, like, “The best pizza topping is pepperoni,” or make it art-related, like, “Graffiti is art.”

- Give students ten seconds to silently move to the line that corresponds with their opinion.

- Call on students to explain why they chose that line.

- Move back to the center base and repeat.

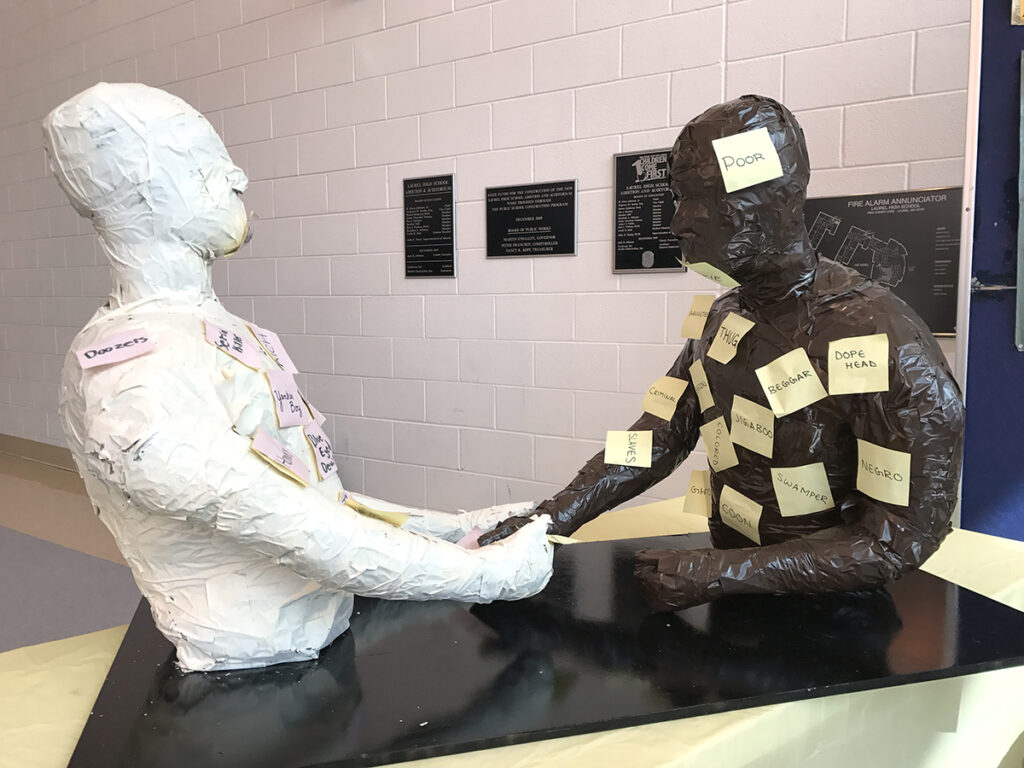

Scenario 3: Behaviors

The Situation

It’s time to dig a little deeper! For another art room scenario, you received a parent email that said, “You didn’t give me any notice about my child’s failing grade. Now it’s too late, and I can’t do anything about it. Because of this, you need to change the grade or give her makeup work!” Most of us would read this email, cringe, and then get fired up! “How dare they accuse me of failing their child? I did XYZ to support them…” and down the rabbit hole we go.

Now, imagine you got an email that said, “I received my child’s report card today, and I was surprised to see a failing grade in art! I can’t believe I didn’t realize this sooner. Is there anything you can do to change the grade or provide makeup work?” This use of “I” language softens the tone and shifts the responsibility to the parent instead of you. The parent is no longer making a demand but a request. You would probably be much more likely to work with the parent and student to rectify this situation.

Let’s take a peek at a student example. You can tell your students, “I expect you to write your name on your projects. If your paper has no name, I won’t know whose it is!” You are expressing your expectation with a reason why. You are giving your students the choice to write their name or maybe have it go missing. On the other hand, if you told a student, “You should have written your name on this! No wonder it got lost!” it puts all of the blame and shame on the student.

Why It Feels Tense

When another person points out our behavior, we often feel attacked. After all, we made a choice and did (or didn’t do) something for a reason. It may seem like our judgment is being called into question. No one likes to feel like they are wrong!

Options for Leaning In

But as art teachers, we may find ourselves in situations where our administrator or a parent is giving us critical feedback or reprimanding us. We may also be the ones providing constructive criticism or correcting behaviors with our students. How you word conversations can make all the difference!

Let’s revisit “I” language with the following statements:

- I would prefer…

- I need…

- I want…

- I desire…

- I expect…

- I would like…

- I would appreciate it if…

Encourage your students to use “I” language to express what they are looking for versus what their peer, in their opinion, “should” be doing. Reiterate that their peer has a choice, and it’s not always reflective of whether or not they like or dislike them. Their peer can choose to comply and agree—or they can disagree.

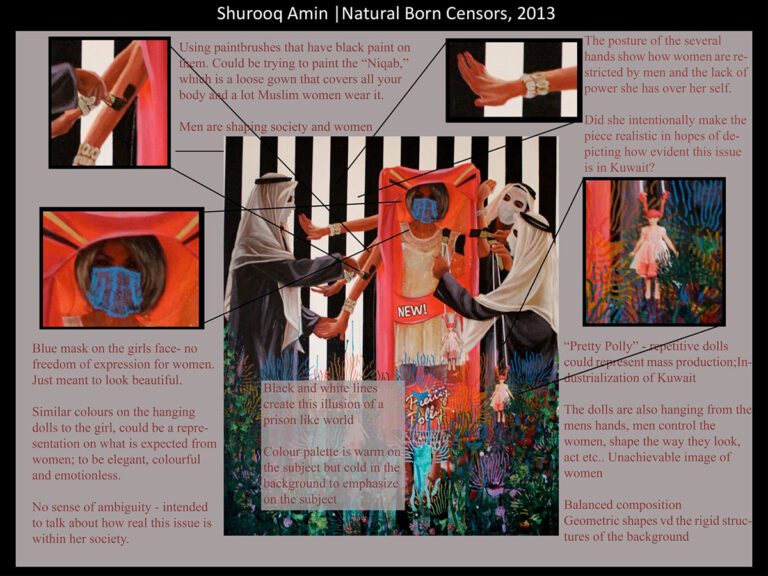

Scenario 4: Core Belief Systems

The Situation

Let’s look at a recent example from the news you can use as a practice discussion with your students. A few months ago, Jason M. Allen won a blue ribbon and $300 at Colorado’s State Fair for his piece, Theatre D’opera Spatial. The kicker is that this piece was created with an artificial intelligence (AI) program that turns lines of text into realistic images.

This created quite a controversy in art circles. Some questions that surfaced included the following:

- Did Allen cheat?

- Is this ethical?

- Is this a form of plagiarism?

- Can he call himself an artist or a painter?

- What implications will this have on traditional painting?

- What does the term “art” encompass?

- Is this a responsible use of technology?

Why It Feels Tense

This level of discussion can hit home the hardest. At this level, topics are usually religiously, spiritually, and/or politically based. The beliefs around these categories are essential to one’s formative identity. Because these beliefs are so integrated into who a person is, the lines are infinitely blurrier when it comes to approving or disapproving of an idea, a person, or both.

Options for Leaning In

Established norms around a safe classroom environment that values trust is key. Do this through team building, “I” statements, active listening, and appreciation for others’ honest contributions.

When sensitive topics come up, remind students of the following:

Let’s go back to our AI example. The first step to having a solid discussion on any topic is to be as informed as possible. This requires quite a bit of research, including what AI is, then looking at the topic from as many perspectives as possible. Check out these two articles (1, 2) for more resources on how to scaffold the research process with your students.

Here are some resources to get started:

Note: Be sure to review all resources before determining if they are appropriate to share with your students.

- The text-to-image revolution, explained

- An A.I.-Generated Picture Won an Art Prize. Artists Aren’t Happy.

- Should AI-Generated Art Be Considered Real Art?

Next, pose questions. They can be the questions above, or your students can generate a list of questions during their research. For a fun and anonymous way for your students to contribute questions, check out Snowball Responses.

Here are ten helpful tips to keep the discussion calm and friendly:

- Review the class norms.

- State clear expectations about participation, such as, “It’s okay to refrain from speaking. However, everyone will participate by exemplifying support and respect.” Or, “Everyone speaks once before anyone speaks twice.”

- Provide time for students to prepare by jotting down their thoughts in a sketchbook before diving into a discussion.

- Make it a game with activities like the Fish Bowl or Inner/Outer Circle.

- Sit in a circle to encourage face-to-face interactions.

- Try elbow partner or small group activities for the first few questions to build confidence. Work your way up to whole class discussions.

- Pass a special object to promote active listening. Only the student holding the object can speak. Make it fun, and use an art-themed prop!

- Employ a one-minute timer when speaking. Timers force students to pare down what they say to the essentials and promote consideration for others’ time.

- Use “I” statements.

- Snap fingers when someone says something that is profound or resonates with you to show support without interrupting.

Art is everywhere; it covers and connects all disciplines and content areas. Because of this, art critiques can get a little messy when an artist’s intent or an artwork’s subject matter is on a sensitive or controversial issue. Even when we are looking at and discussing artwork made in our art rooms, providing feedback can be tricky! Because our young artists pour themselves into their masterpieces, it can be hard to separate comments about their artwork from their character and identity.

The scaffolded strategies and tips above can help create a studio environment that welcomes constructive criticism with less hurt feelings and personal slights. Build trust and positive relationships through team building, a focus on “I” statements, active listening, and a show of support and appreciation. If you decide to dive in deep with your students, prepare to be blown away by their insightful thinking and passion!

How do you foster open-mindedness in the art room?

Share a critique or discussion activity your students get excited for.

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.