Final exams are extra tricky when it comes to art. What really makes up a semester or year’s worth of learning? From multiple-choice district assessments to final artwork projects, finding the perfect assessment is important. While knowing vocabulary and techniques is essential, a multiple-choice test won’t assess the application of skills students have been practicing. The best way to demonstrate learning is to actually demonstrate it.

You may be tempted to give an artwork as a final assessment, but keep in mind the following three tips.

1. Don’t cram in a new technique.

Final artwork expectations often incorporate one last, new technique that we try to cram in at the last minute. In doing this, we aren’t giving students time to learn and develop this new technique through low-risk practice before applying in a high-risk situation. This isn’t an authentic assessment of what they have already learned over the semester through practice.

2. Don’t penalize students for taking risks.

When assessing what students actually gained in your class, it’s important to consider risk-taking, exploration, and other critical skills you’ve helped them develop over the semester. If a student took major risks to try something new or something complex, the rubric doesn’t usually take that into account. If risk-taking is something you value, it’s important to include that in your assessment and make sure students have been aware of that all semester (or year) long.

3. Don’t make it stressful.

Creating a final artwork is high-risk and stressful. What if that artwork just didn’t come out as great as expected? When students are cramming for every other class simultaneously, it’s hard to focus on creating (especially outside of class time). One artwork as a final assessment also doesn’t account for all that has been learned, nor does it account for growth over time.

Instead, consider the following six strategies when creating your final exam.

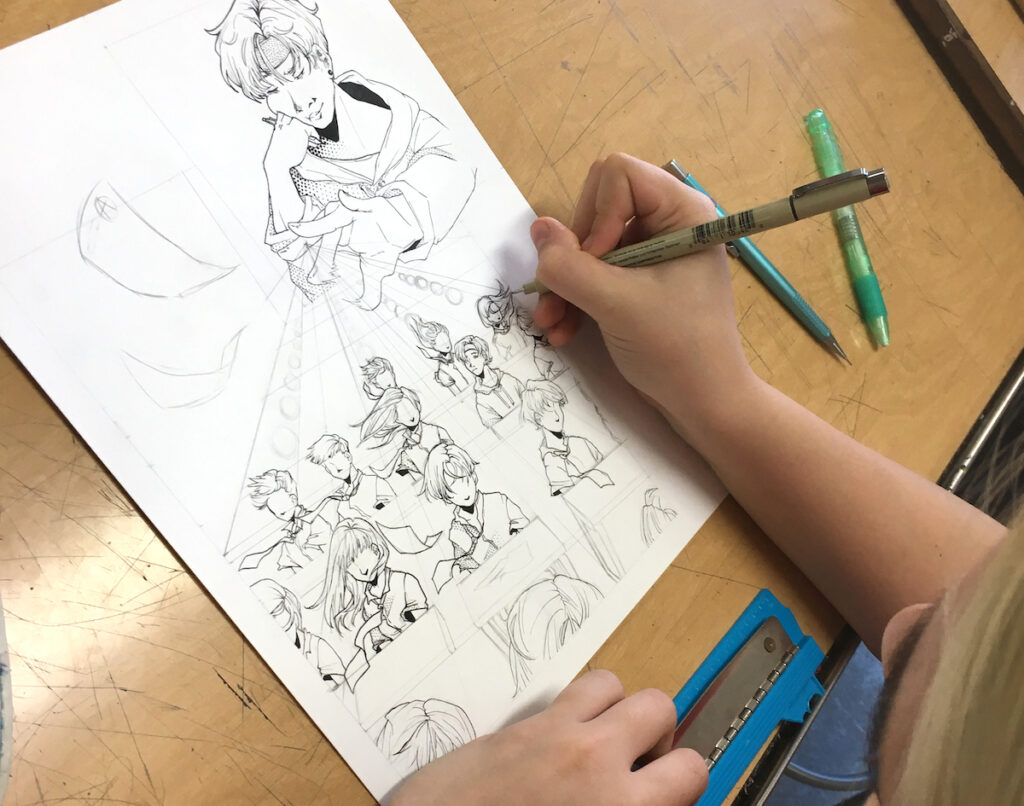

1. Assess what they already know.

Assess the application of skills already practiced and applied by revisiting past work. Have your students choose one artwork over the semester (or year) they would like to redo. By the end of your time together, students should have honed their skills and developed more techniques. Allow students to choose how to show what they have learned. Students take ownership of their learning when they connect personal interests to their growth as an artist. By comparing apples to apples, students can show off how much they’ve developed over time.

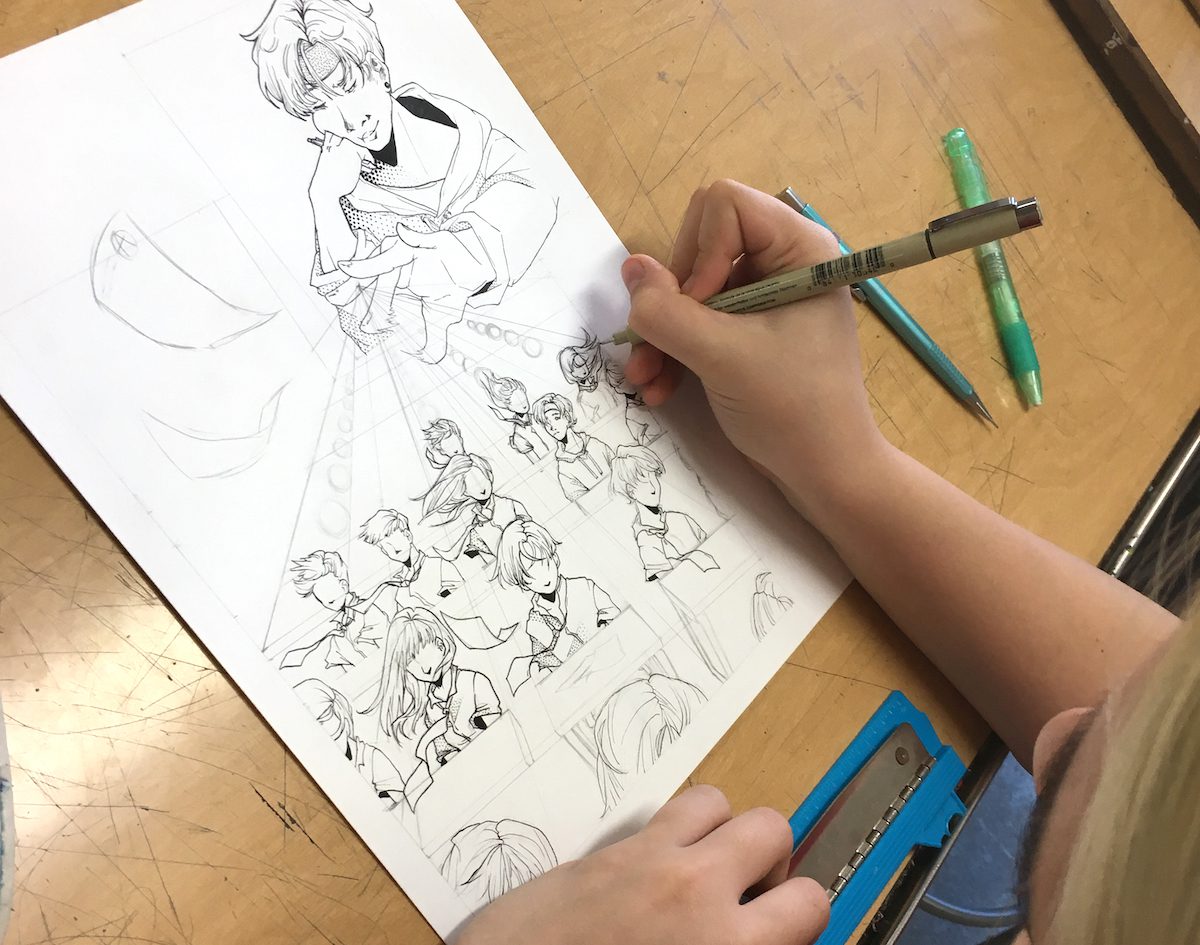

2. Support students during the planning phase.

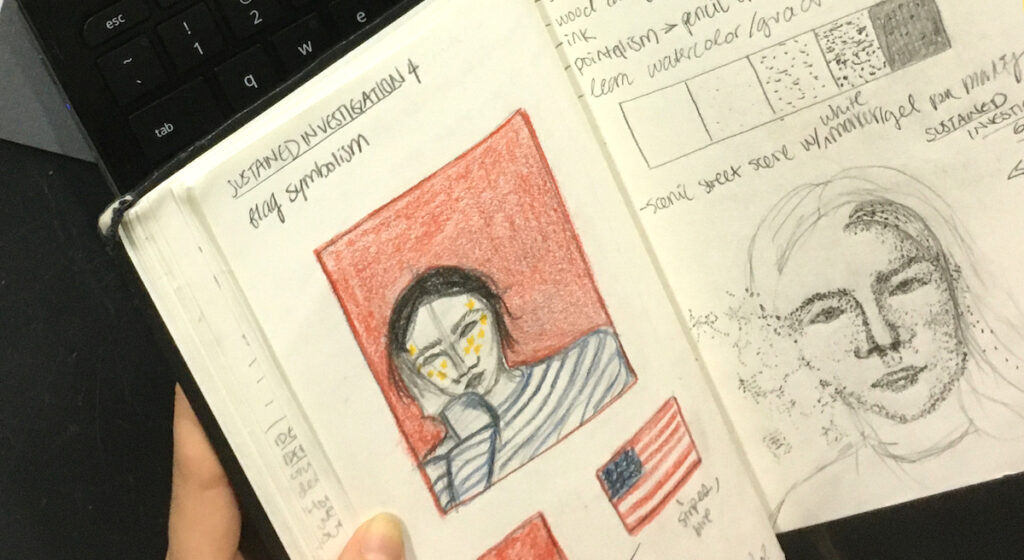

Planning should absolutely be part of the final assessment. However, you don’t want to set your students up for failure if the start of their artwork is not strong. Score them on your rubric based on their level of planning, but don’t leave it at that. If students are struggling in the planning phase, you can’t be surprised when their final artwork is less than stellar. Provide feedback so your students can make the best decisions for their final artwork.

3. Give room for risk-taking.

If you do cram in additional techniques by the end of the semester, make sure to account for this on your exam rubric. Allow opportunities for safe practice and formative feedback. Don’t leave students to practice a new technique without knowing how to better prepare for their final assessment. Include self-reflection in the final exam so students can talk about what they learned from the new experience and how that new experience impacted their overall work.

4. Allow choice from a list.

When reviewing all the techniques and concepts learned over time, let students choose their strengths to show off. Provide an open-ended prompt and a word bank. Students can choose three of the ten listed techniques they practiced. Ask them to create on a smaller scale, forcing students to take more time on their techniques and concept and less on filling a large canvas.

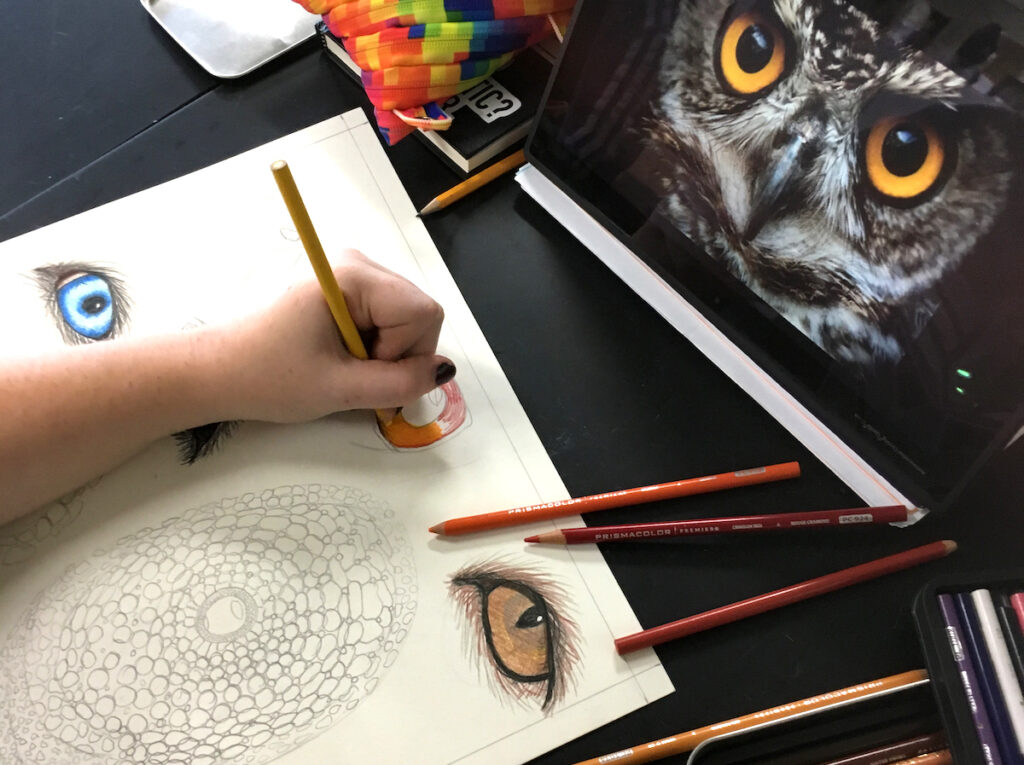

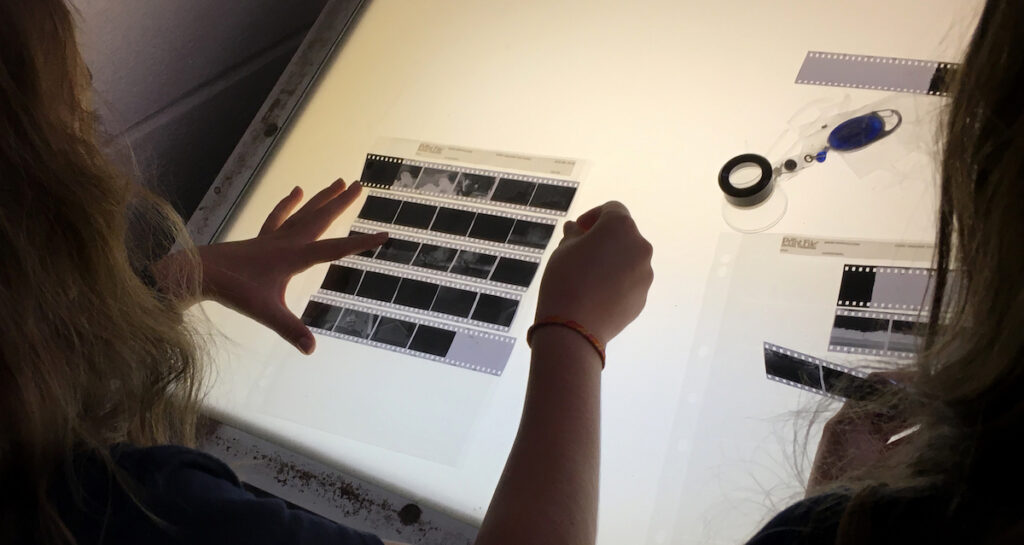

5. Allow enough time for mistakes.

If your student is working in a medium prone to mishaps, such as film photography or ceramics, it’s helpful to avoid rushing when they face an unexpected setback. Of course, students should plan accordingly and not procrastinate. Time management is a big part of teaching art, as well. But you also don’t want to “catch them” when circumstances might be out of their control. Make sure to provide alternative options for when their greenware piece falls off the table after weeks of progress.

6. Use a portfolio instead of one artwork.

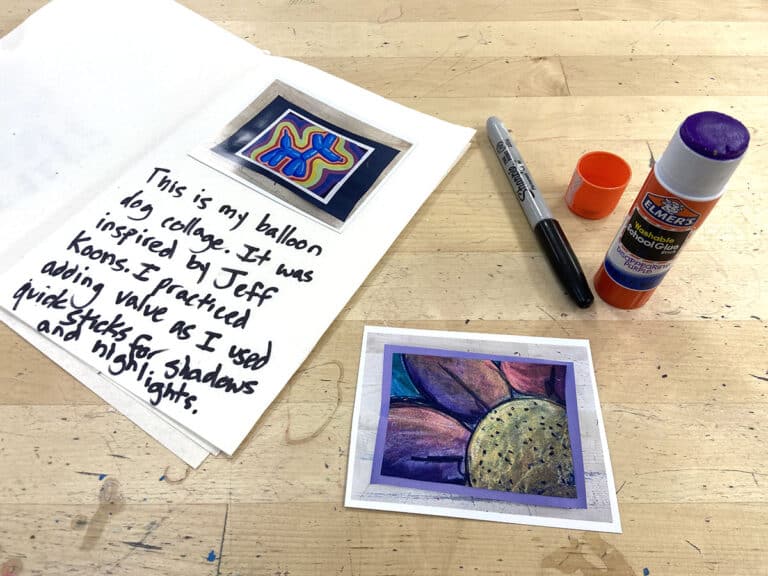

Try using a growth portfolio as your final exam. Students can start making the growth portfolio on day one and develop it over time or even in the last month of class. Creating a portfolio that highlights how far students have come over time will be both eye-opening for students and will allow you to see which aspects students have grown. In a growth portfolio, students create a digital or physical portfolio filled with documented learning artifacts. Students can write about their growth or present to the class or in a small group setting.

The weeks leading up to final exams are stressful for both students and teachers. Remember, your students have six other classes to study and prepare for. They are also finishing up other big projects and making up late work. As teachers, there is never enough time to teach everything we want. And we all know we are catching up on grading before the big crunch. Take time now to review your final exam to ensure authenticity and alignment with your values and expectations.

How are you giving final exams this year?

How do you prepare your students for their final exam expectations in your art class?

What criteria do you use to assess final exams? What essential skills do you value?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.