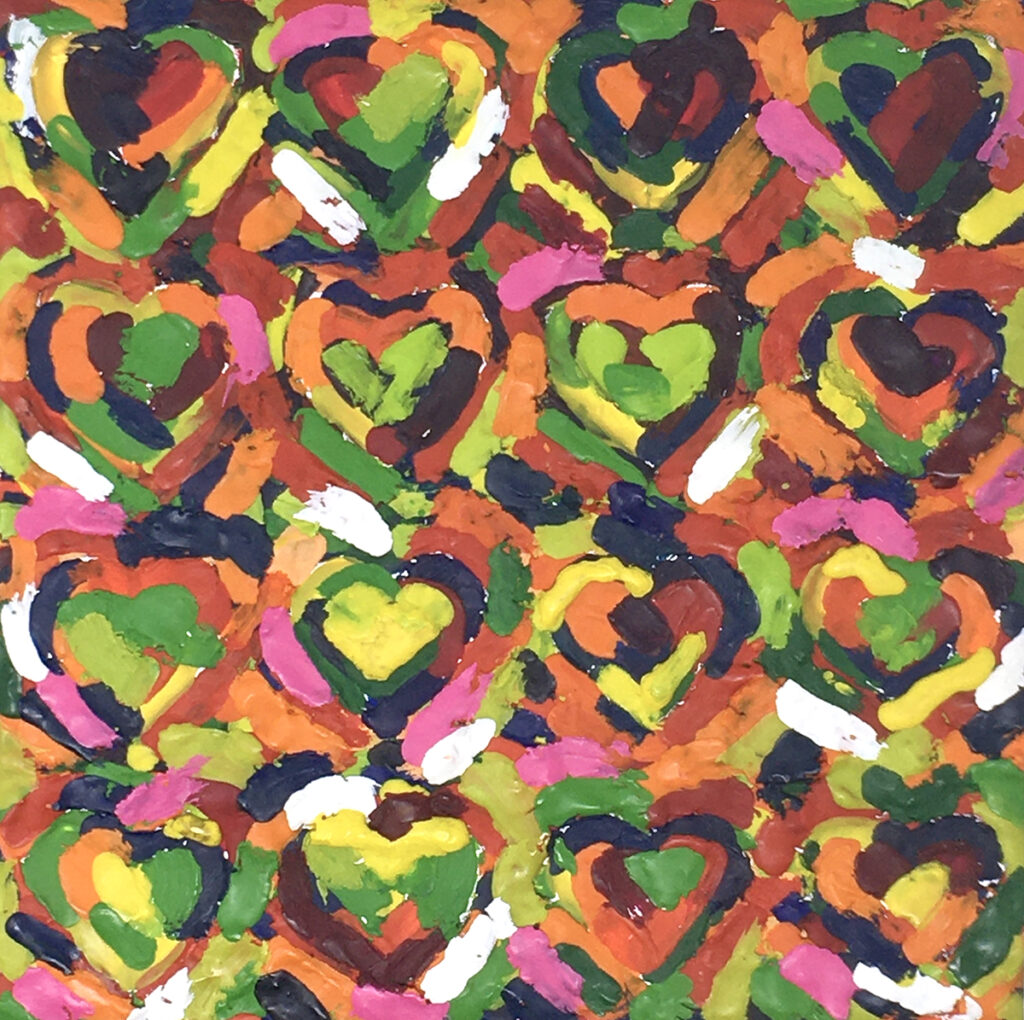

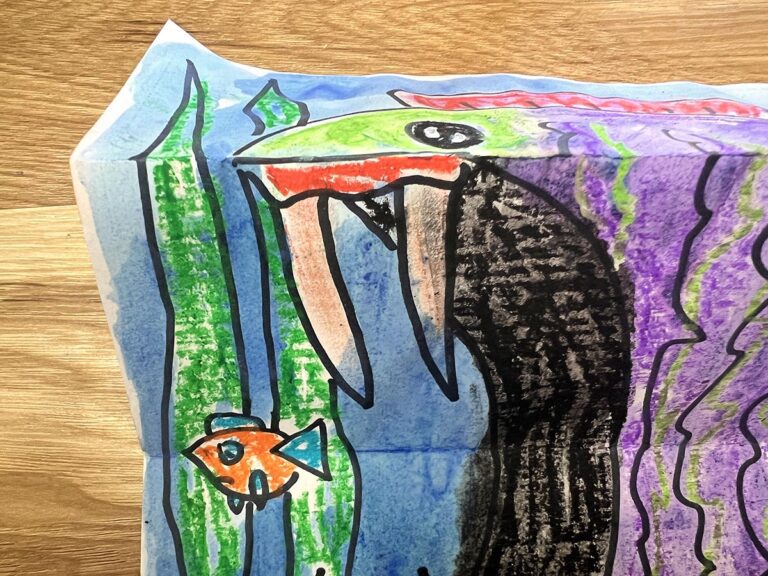

We’ve all received drawings covered in hearts because they’re about love. Or perhaps you’ve received landscape paintings of trees about nature. As students develop an understanding of the world around them, it’s formed with specific, concrete, and repetitive images. There’s nothing inherently wrong with using hearts or trees in an artwork. After all, students are using the visuals they know.

The beginning of the school year is when we see a lot of these trite symbols. As the year progresses, the goal is to challenge students to think beyond clichés to create more personal and meaningful artworks on their own. But how do you get there?

What exactly are clichés?

Before we can look at how to challenge clichés, we need to understand what they are. Clichés are overused, repetitive phrases. While they’re often unoriginal and stale, they can also be familiar and comforting. Clichés collectively connect us without a moment’s thought. In the art classroom, the cliché includes imagery and symbols to convey meaning. Like the example above, when we see a heart, we equate it with love. Show us a dove with a branch, and we think of peace.

Are clichés bad?

Developmentally, the use of clichés helps us form a sense of understanding and camaraderie. Young children learning how to communicate thoughts and feelings have a limited verbal and visual vocabulary. They discover that if they use a smiley face, adults and peers will know it means happiness. It takes time, maturity, and practice to identify and share complex feelings, such as frustration, elation, and confusion.

Clichés are not bad. But we do need to help our students dig deeper by reflecting on and shifting how we work with symbolism and meaning in artwork.

Use these eight tips to stretch your students beyond the cliché as they dive back into artmaking this year.

1. Address the elephant.

First things first, meet your students where they’re at. You wouldn’t expect a first grader to know how to depict love in a sophisticated, complex way. Why should you expect more from your freshmen? Students mature physically, mentally, and emotionally at different rates. You may have a sixth-grader who can express a vast array of emotions through everyday objects in highly symbolic ways. You may also have a senior who struggles to consider anything beyond hearts and stars.

The next step is to openly discuss clichés. Share a list of commonly used themes with your class. Ask students to draw the first symbol that comes to mind for each theme as you read down the list. Start tallying how many love hearts and peace doves you get as a class. This is a great way to show students how often we use the same pictures to convey a specific meaning.

Group students into teams. Challenge each team to come up with as many different ways as they can to depict love or peace. Give them a time constraint so they’re encouraged to work together to problem-solve and generate new, unique ideas. Will all of these ideas be stellar? Probably not, but by taking the time to push ideation, they’ll learn to identify cliché imagery. It will also provide a jumping-off point for where your students are.

2. Acknowledge the trite.

Despite our best efforts, some students are still going to use clichés. They may struggle to think beyond the basic symbolism or they may feel stubborn about using certain imagery because “that’s what they like.” Don’t wait until their artwork is finished to address the trite symbolism. Start working with students in the planning stage.

Identify and label the imagery for what it is, but be aware of how this might make students feel. We don’t want them to feel shame for their artistic decisions. Instead, use questioning strategies to support deeper thinking.

3. Let the love flow.

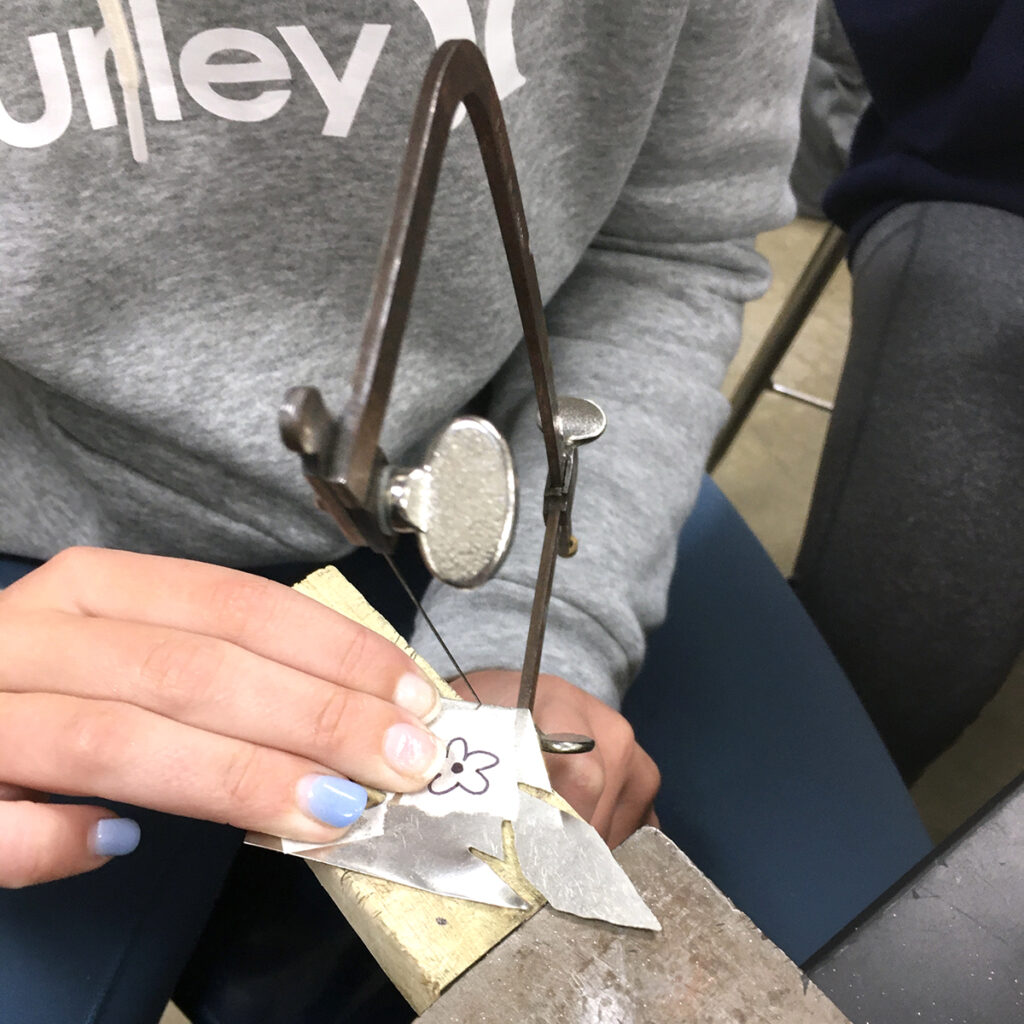

When starting a unit where students learn to saw metal, they inevitably design a heart pendant for their best friend or a paw tag for their furry family member. Instead of fighting that uphill battle, let them create using these simple shapes. Learning how to saw metal is risky enough. Take the conceptual pressure off and use a cliché shape to focus on skill proficiency. Students gain practice and get those symbols out of their system.

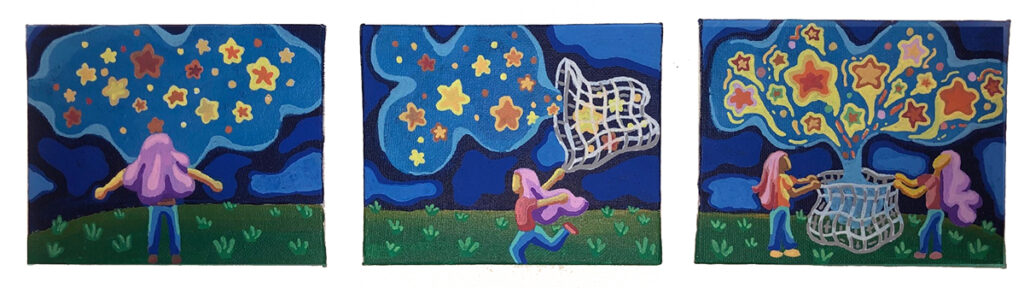

4. Go beyond the first thought.

Another exercise is to focus on one theme. Push students to create as many versions of one universal theme as they possibly can before settling on their final imagery. The exploration doesn’t have to focus on the subject matter. Talk about ways to expand clichés through other artistic choices, such as line weight variation, unexpected color schemes, or layered media. Check out How to Get Your Students to Move Beyond Trite Imagery and Develop Original Concepts for more ideas.

5. Explore cliché media.

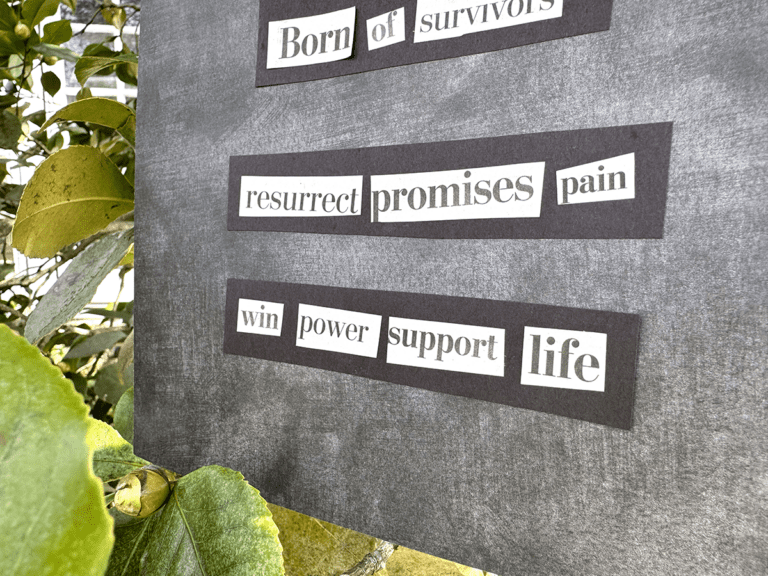

Introducing collage to a level one art class results in selfies taped to a bedroom wall. Even the way media is used can be cliché! Let’s look at the universal theme of identity. Students tend to look through magazines in search of their favorite foods, colors, and material objects. They often cut them out in squares and paste them, filling the page, or even worse, just floating in the middle of the paper!

Instead, teach different ways to cut and tear papers to fill a self-portrait. Students search for colors and textures that make them feel at home. Cut up imagery that addresses the prompt “why I matter” and arrange it in the background or as clothing. Show students how even though they all started with the same, broad theme of identity, each work reflects them as individuals.

6. It’s not always about world peace.

When students hit advanced levels, we expect them to dig deep, create a body of work, and synthesize media for rich meaning. That’s a high expectation for even the most experienced artists! Remind students that art doesn’t have to be about saving the earth from global annihilation or other controversial, social justice topics.

Art can also be about intentional mark-making, exploring the relationships between shape and color, or observing the wonders of nature. When students explore art for its inherent characteristics, they leave the overused symbols behind.

7. Let them use clichés.

Students might need to create with rainbows and smiley faces—let them! They might be working at their own level. Anything more complex could be too emotional to bring up without a professional counselor. Often, students need the safety of the familiar to take other risks. Sometimes, students don’t connect with a specific prompt, and this is their way of avoiding the topic.

Help build artistic confidence by supporting students’ decisions. Provide them with feedback on ways to push their work further. Ask open-ended questions to find out more about their choices. Maybe they were excited about creating with stars and realized later that it wasn’t so great. Ongoing support and feedback will help students come to these conclusions on their own, which makes the learning more meaningful.

8. Connect with artist inspiration.

What if you have a student who still digs their heels in? If you have a student who’s passionate about using cliché symbols, find artists who work with universal concepts and symbols in an innovative way. If hearts and rainbows are your student’s jam, have them look at artists like Stacie Swift, Lisa Congdon, and Mel Bochner. Your students may learn how to transform their symbols through the influence of these artists.

Let it go.

Remember, it’s their artwork, after all. Perhaps they don’t get the best grade in conceptual thinking, but ultimately, that’s up to them. Your role is to guide and support them through the artmaking process. You can prompt a student to think deeper with mind mapping and research. You can teach students multiple ways to approach a topic. You can demonstrate how to expand their artistic complexity. When it comes down to it, they get to decide how they’ll express themselves through their work. The important part is that they are making art, growing, and having a blast!

What are the top three cliché images you see in your room each year?

How do you identify and discuss clichés in your classroom?

What are your favorite strategies to push deeper thinking?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.