Once you are released into your art room, you are in charge of the growth and learning of every student with whom you work. This can be daunting, especially if you have little to no background in special education.

Unfortunately, this is a reality for most art teachers. Whether you teach a few courses or every student in the school, it can be tricky to keep track of and implement all of those IEPs!

Today, you are in luck. We are going to walk through the basics of inclusive education in the art room. We’ll go through the laws and ideas you need to know to be able to address the needs of all your student artists.

To delve into this important topic, I reached out to Jenna Gabriel, the Manager of Special Education at The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Together, we outline the big ideas behind inclusive education as well as how they specifically relate to art education and provide you with resources to support you in this work.

Here are three tips to help you understand inclusion in the art room.

1. Make sure you have a basic understanding of special education laws.

To begin, I asked Jenna to outline the special education laws and how they impact art teachers. Here is what she shared with me. (Italics denote text contributed by Jenna.)

Four federal laws intersect to support educational access for students with disabilities. Two of these address discrimination. The other two address education specifically.

Laws 1 and 2: The Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504 and The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA)

The Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 are civil rights laws. These laws are intended to prevent discrimination on the basis of disability in all walks of life—which means they apply in our schools, though the laws themselves are not education-specific.

These laws prohibit discrimination against individuals with disabilities who require support from the physical, programmatic, or communication environment in order to access activities provided by the school and the well-rounded education to which students are entitled. This includes access to the general education curriculum.

These laws define disability quite broadly to ensure students with disabilities receive the full protection of the law. Because this definition of disability is broader than that in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, described in full below), students with disabilities who do not receive special education services on an IEP plan may still receive appropriate accommodations under a 504 plan. Regardless of any accommodations put in place by the school on a 504 or IEP plan, the rights of any student with a disability to access the educational environment free from discrimination are still protected under these laws.

It’s important to note, though, that these two laws do not provide dedicated financial support to schools for implementation, and funds schools receive under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) can only be used to serve students with IEPs.

Law 3: ESSA (Every Student Succeeds Act)

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) is the primary federal education law. It provides funds to the states to support educational achievement for all students in K-12 public education. Signed into law by President Obama in 2015, ESSA touches on a few interesting aspects that affect students with disabilities in the arts.

First, ESSA offers a definition of “well-rounded education” that is extraordinarily arts-friendly. By acknowledging all students must have access to a well-rounded education, the definition of which includes the arts, the law affirms the right of students with disabilities to participate in arts learning, just as their typically developing peers do. It does not go so far as to require arts education, (that’s up to the states!) but it does support the claim that if a state includes the arts in their plan to provide a well-rounded education to all students, students with disabilities have an equal right to receive that instruction.

ESSA also acknowledges the importance of adequately prepared teachers, which is important in this work, as we know students with disabilities require specialized instruction and supports. For art teachers who often have students with disabilities included in their classrooms, this preparation is critical to providing equal access to meaningful arts engagement. Yet, statistics that have remained disproportionately static over the last thirty years show us that less than 25% of practicing art teachers received even one course in special education while in college. Furthermore, nearly two-thirds don’t feel equipped to meaningfully engage their students with disabilities in art instruction.

Law 4: IDEA (The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act)

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act is the federal law that most specifically addresses the needs of students with disabilities. This law outlines thirteen disability categories; a student must be diagnosed with one of these in order to receive services, and the disability must affect a student’s educational performance. This is a key difference between the definition of disability under IDEA and the broader definition under ADA and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504. Under IDEA, specially designed instruction is mandated. This includes adaptations to methodology and content that far exceed accommodations for access a student would receive on a 504 plan. It also calls on educators to provide that individualized instruction in the least restrictive environment—which the law tells us is alongside a students’ nondisabled peers to the maximum extent appropriate.

If you are looking for some streamlined information about IDEA, check out the handy download below. It will take you through the six core tenets and what they mean for you and your students in the art room.

Because we know art teachers see most students in a school, including those with significant learning needs, the thirty-year trends in art teacher preparedness Jenna describes are alarming. We must work to change this! It’s why I believe so passionately in the importance of supporting art teachers in developing these skills.

Here are three suggestions if you need more support in this area.

1. Take a course.

If you’re looking for an opportunity to grow your foundational knowledge and connect with other art teachers, consider one of AOEU’s courses. Autism and Art and Reaching All Artists Through Differentiation are two great choices. These courses will help you develop strategies and techniques for meeting the needs of all learners in the art room.

2. Attend in-person professional development specifically designed to support you in developing these skills—and connect with others from across the country while you’re at it!

The Kennedy Center’s Office of Accessibility and VSA aims to ensure the arts are accessible to students of all ages. They provide resources, conferences, lesson plans, webinars, online courses, networking opportunities, and more.

3. Seek out other PD that specifically addresses your knowledge gaps.

Here are some resources from AOEU:

- Teaching Adaptive Art PRO Pack, which can be found in PRO Learning

- Setting Up an Autism-Friendly Classroom PRO Pack, also found in PRO Learning

- 4 Concrete Ways to Modify Art Projects for Students with Special Needs

- How to Work with Students with Special Needs in a Choice-Based Space

2. Learn the difference between differentiation, accommodations, and modifications.

After Jenna explained the legal side of things, I asked her to talk about different ways art teachers can work with students with special needs. She told me, to start, it was important to lay out the differences between differentiation, accommodations, and modifications.

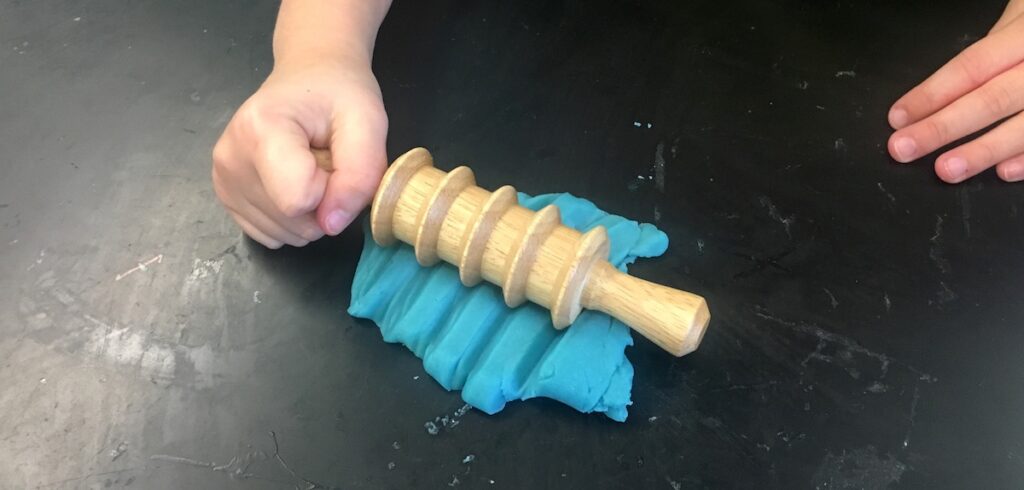

According to Jenna, differentiation in the art room is key when we look at meeting the needs of all learners. She describes differentiated instruction as a proactive approach to lesson design that responds to students’ varying interests, readiness levels, and learning styles. For most students in a room, this flexible and responsive approach will be enough to engage students in instruction.

We know, though, that some students will require additional support or adjusted approaches. These, Jenna shared, are called adaptations. Adaptations include both modifications and accommodations. Although we often use these terms interchangeably, they are actually different! I asked Jenna to provide an outline of these differences, and examples of how they might look in an art room.

Here is what she shared with me. (Italics denote text contributed by Jenna to this piece.)

Accommodations

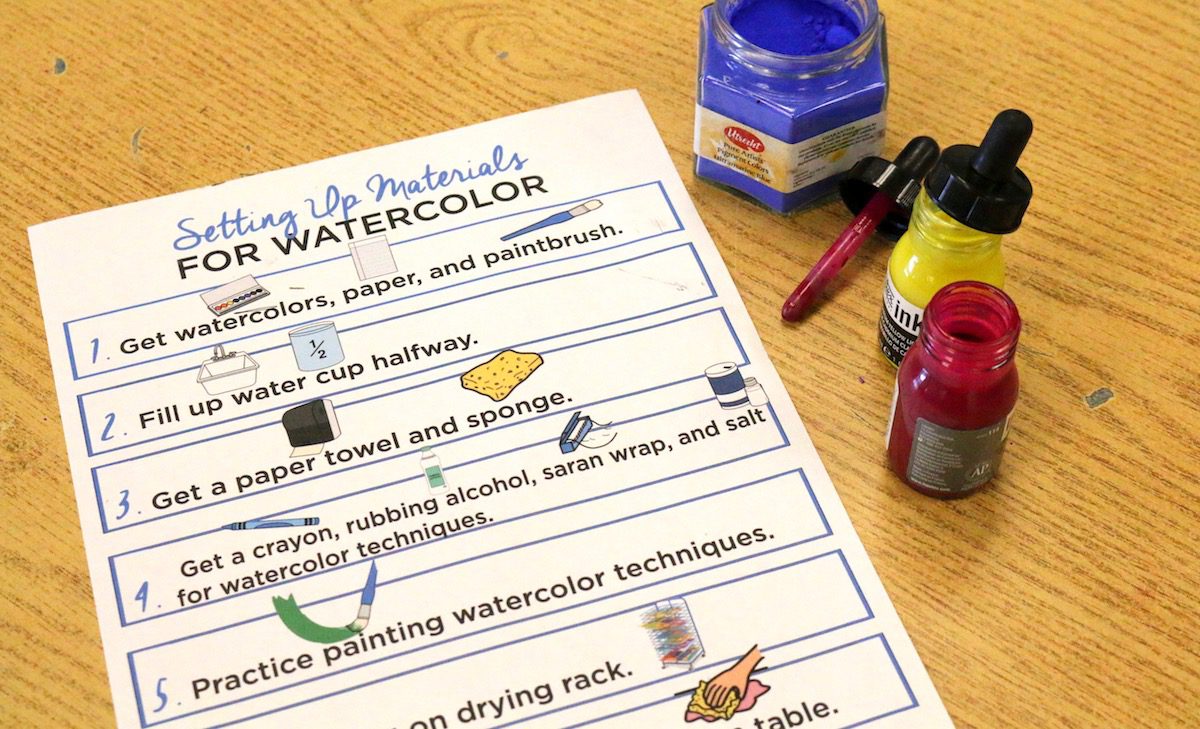

Accommodations are adaptations we make to the educational environment that allow students with disabilities to participate in the same activity as their peers. They can include classroom setup, tools, and materials—anything that works to remove a barrier to participation in the activity.

For Example:

- A specialized grip to make cutting paper easier, or an adapted grip for a paintbrush.

Adaptive tools are often low-to-no cost or can be made yourself—like inexpensive adaptive scissors or pushing a tennis ball onto a paintbrush so a student with fine motor deficits can hold his paintbrush. For many students, these tools may be all that a student needs in order to take part in an art activity such as collage or painting exactly as you designed it. - A pair of gloves or alternate material during a clay unit

Some students struggle to participate in certain art activities because of sensory aversions to the feel of materials like clay. Offering students a pair of gloves, allowing them to manipulate clay inside a plastic bag, or providing alternate material like Model Magic, might be enough for that student to participate fully in a sculpture lesson in which your primary learning goal is about clay as a medium.

Modifications

Students with more significant needs might need a modification—an adaptation to instruction or content that, unlike with an accommodation, necessitates modifying the activity itself.

For Example:

- Allowing a student to collage instead of paint.

Let’s say your lesson asks students to imagine a symbol and paint it. In that assignment are myriad complex cognitive skills–flexible thinking, planning, translating an idea into a design—in addition to the artistic skills related to paint as a medium. For some students, the cognitive leap of understanding what a symbol is and how to communicate it may be too challenging, for others the challenge may lie in the cognitive act of imagining something new and communicating it. Collage can offer students struggling with this part of the process a visual vocabulary to draw from, reducing the complexity of the assignment while still supporting participation in the creative process.

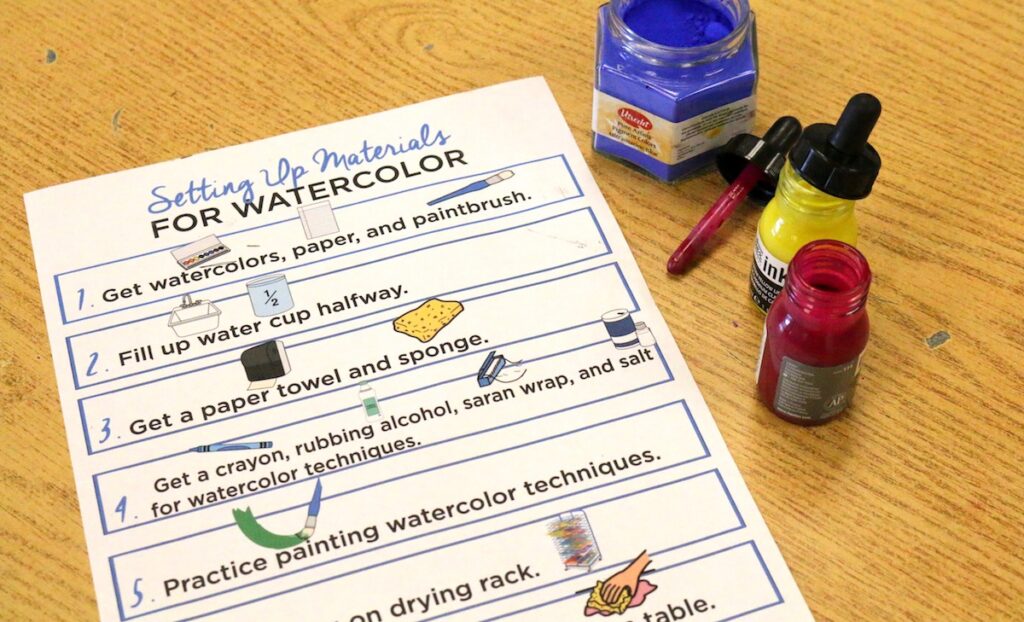

- Allowing a student to demonstrate individual clay sculpting skills instead of combining skills in an intricate sculpture.

An intricate sculpture assignment also combines multiple skills: perhaps you’ve asked students to slip and score to construct a free-standing structure or to coil clay to create a vase or pencil holder. For students still struggling with foundational skills as their peers progress into complex sculpting, you might offer the alternate activity of demonstrating the individual skill—for example, creating a simple coil of clay. In both of the above examples, it’s important to note the modified activity is still tied to the learning goal of the lesson: students doing collage are still utilizing visual symbols in their artwork, and students demonstrating foundational clay skills are still demonstrating their understanding of clay as an artistic medium. For situations in which you might consider offering an alternate activity, it’s important the proposed activity remain aligned to the learning goal you’re exploring with the rest of the class. This helps promote inclusion and full participation, even when the activity has been significantly modified.

3. Concentrate on what is most important.

It’s important to keep the focus on your learning objectives. Determine exactly what you want your students to learn from each lesson and then modify accordingly.

For example, consider a lesson where you’re asking students to create coiled creatures. Depending on the target learning objective, your modifications may vary.

Jenna explains, “If the most important content is related to skill in the medium, a student who does not create a creature from their coiled clay has still worked toward your learning objectives. They have participated in a pottery lesson alongside their peers.” In this case, a student could use coils to build a simple cylinder.

However, if the objective is to use clay to depict an animal, you can modify your instructional approach by providing scaffolds that will allow a student to participate. In this case, Jenna suggests you might provide a pre-assembled coiled base or a selection of pre-made animal features a student could choose from to assemble their sculpture.

In each of these instances, you’ve made significant modifications but ensured the student is still engaging with the same content.

Remember, the goal is inclusion. Your students with disabilities may need some adaptations or support, but they should always feel like they are a part of the class!

So what does inclusion really mean for art teachers? Here are four ways to support inclusion in the art room.

As you’ve probably already gathered, Jenna is a wealth of information when it comes to this topic. Here are four more insights to keep in mind as you support students with disabilities in your classroom.

1. Consider the physical space.

Students with disabilities who come to your art room should be sitting among their peers! However, don’t forget to consider their IEP requirements for preferential seating or limited distractions.

Furthermore, if a student attends art with a teacher’s aide and can work somewhat independently, let them! Suggest the aide circulates the classroom or makes modifications to materials rather than work with one child in isolation. Inclusive settings promote meaningful social relationships and positive behavioral outcomes as much as academic ones.

2. Recognize your students as individuals.

It’s imperative to remember all students have areas of strength and opportunities for growth. Your students with disabilities are no exception! Build relationships with your students to learn what they are interested in and harness their strengths in the art room.

3. Ensure all students have access.

A third important point is there should not be a separate curriculum for students with disabilities. As you can see from Jenna’s suggestions above, meaningful inclusion is about more than welcoming students with disabilities into the art room. It’s about utilizing best practices and evidence-based strategies to respond to students’ individual needs so they can be involved in all aspects of learning—work that, at the end of the day, improves instruction for all your students! Rely on principles of differentiated instruction and the use of specific adaptations to ensure all students have access to the same learning opportunities in your art room.

4. Be both a teacher and a learner.

Finally, as with any aspect of teaching, teachers are lifelong learners. We are reflective and look for new ways to solve the same problems. For students with disabilities, there is a team of educators and specialists dedicated to their educational success. If you are not sure who is available to help, ask!

Look for opportunities to learn and grow right along with your students and celebrate even the smallest of victories. Jenna reminded me that as art teachers, we often see our students in a unique light and see growth that has perhaps eluded educators working in other classrooms. This offers a fuller picture of who our students with disabilities are! Celebrate your students’ success in the art room by sharing it with other members of their team, and you can become an advocate for creative approaches to instruction across the curriculum.

Thank you so much, Jenna for sharing your incredible expertise with us. If you’d like to read more about Jenna, please see her bio below. And, don’t forget to check out more about resources and programs for your students from The Kennedy Center’s Office of VSA and Accessibility here!

_____________________________________

Jenna Gabriel is the Manager of Special Education at The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. She oversees education initiatives affecting students with disabilities and their teachers, including the annual VSA Intersections: Arts and Special Education Conference. Prior to joining the Center, Ms. Gabriel was based in Boston at IBA-Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción, where she directed all K-12 youth development programs. In this capacity, she designed and supervised out-of-school-time programs for ELLs and struggling readers—programming that was awarded the 2016 National Arts and Humanities Youth Programs Award, presented by Former First Lady Michelle Obama. Ms. Gabriel is the Founding Executive Director of Daytime Moon Creations, an NYC-based nonprofit offering arts programs to children with disabilities, and has led arts-based special education programming throughout NYC. Ms. Gabriel holds a BFA with honors in Drama from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts and studied Intellectual Disabilities and Autism at Teachers College, Columbia University before completing her Masters in Education at Harvard University.

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.