Chances are, if you ask your students what art is, many will say, “Drawing and painting.” Even when other adults or colleagues find out you teach art, their responses usually run along the lines of, “I can’t even draw a stick figure!” Drawing is the medium primarily associated with art, and sculpture is usually an afterthought.

Be honest—how many three-dimensional projects do you incorporate in your curriculum? It is difficult to remember sculpture in our art classrooms if we aren’t teaching a siloed ceramics or sculpture course. If you teach a focused drawing course, have you thought about incorporating a three-dimensional project here or there to amplify drawing skills? Suppose you teach a foundations course or a general art class at the elementary or middle school level. Have you considered how adding a sculptural component could enhance engagement and push artmaking to the next level?

Debi West is going to help us answer these questions! Debi is a retired art educator with over thirty years of teaching experience. As a former writer for the online Magazine and an adjunct instructor for our graduate courses, she is a valuable part of the AOEU family. Debi has experience teaching drawing, watercolor, printmaking, and tempera and acrylic studio courses; however, she has particularly loved her last four years facilitating the sculpture course.

“But what if…”

Before we dive into how sculpture creates better drawers in your art classes, let’s take a quick moment to address some questions and put your reservations at ease.

“But what if…”

- “… I am not confident with sculpture?”

First off, you can always learn! The great thing about art teachers is that we are reflective, and we love to learn. You can learn by asking other art teachers, experimenting during your planning period, watching and reading tutorials online, or taking a class like our Studio: Sculpture course. Debi loves watching teachers have their “lightbulb moment” when they get excited about sculpture and all the possibilities that come along with it. When we learn with our students, they respect us, and it keeps us fresh and relatable. We can model the artistic process and troubleshoot when something goes wrong—which is bound to happen! - “… I don’t teach a sculpture course?”

This is an even better reason to add the occasional sculpture project to your curriculum. Debi explains that we can’t dismiss sculpture—art is both two- and three-dimensional. Art is not just a sculpture park but also buildings, chairs, cars, and jewelry. By exposing your students to as many mediums as you can, they will have a broader understanding of what art is. Plus, they may even end up loving three-dimensional art and want to pursue it down the line. - “… it’s too expensive for my budget?”

There are many budget-friendly ways to include sculpture. At the bare minimum, Debi has created fabulous sculptures with the following supplies: a cardboard cutter or scissors, an adhesive such as a hot glue gun and sticks (use low temp guns for elementary), tons of recycled and donated items, and strong classroom management for a safe studio. - “… I don’t have enough storage space?”

No storage space? Try smaller-scale sculptures by giving students a size constraint. Debi coined her size constraint policy as the “Size-O-Meter Box”—each sculpture could not be larger than a designated box. On the flipside, try doing larger-scale sculptures; make it a collaborative effort with fewer pieces to store. Stack bookbinding or bas-relief cardboard projects or stick them in portfolios. Debi also suggests storing in-progress pieces in public display cases throughout the school. Even though the artworks are not complete, they show the school community what you are working on in your room. You can also stagger three-dimensional units, so you only need to store a class or two’s work at a time. - “… I already know a lot about sculpture?”

This goes back to the first point—we are awesome at our jobs because we continue to stay reflective and learn. Even the most experienced in sculpture can grow in their knowledge and practice. The sculpture course has an advanced techniques unit that explores engineering and coding devices, lights, batteries, gears, and more!

Let’s examine 6 ways integrating sculpture into your curriculum can make your students better drawers.

1. Maintain rigor and engagement.

As an art teacher, I think drawing is fun! Unfortunately, many students do not feel the same way. Some students love drawing while others get bored. Switching things up with a sculpture activity or project now and then will break up the monotony of the curriculum. It can also support skills and learning in a new way. Throughout Debi’s thirty-plus years of experience in the art classroom—no matter the grade level—students consistently perk up when they hear they are about to make a sculpture!

2. Reinforce how to analyze a subject.

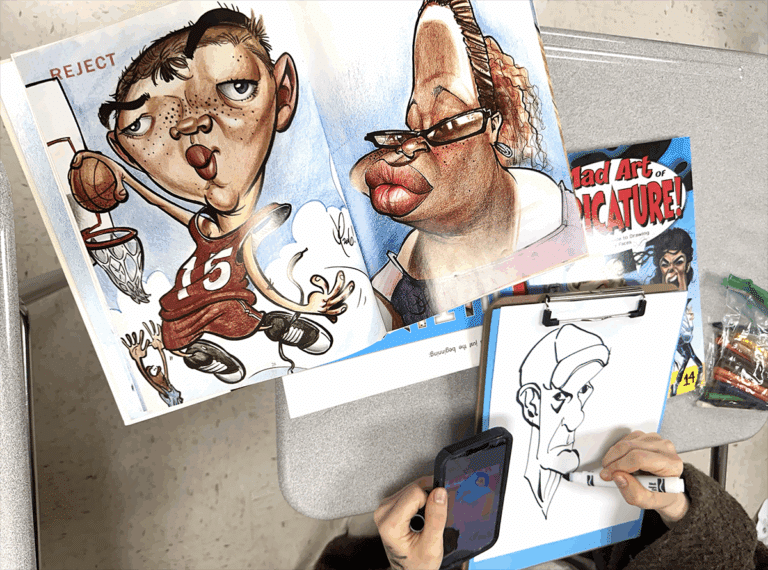

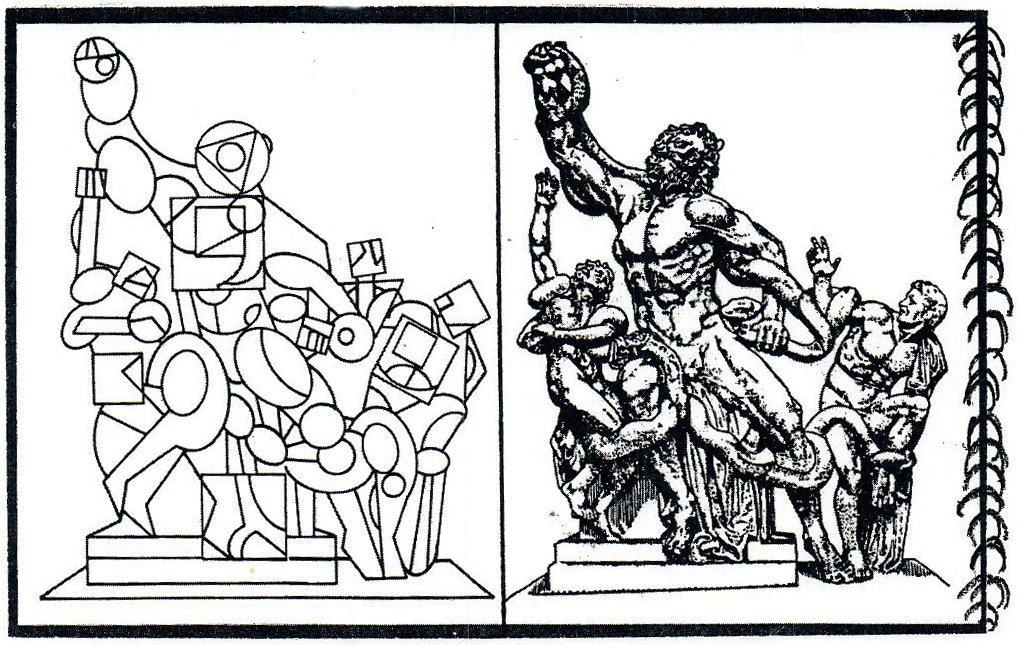

Drawing requires you to look at the person or object you are drawing and break it down into basic shapes before adding details. Sculpture is very similar in that it requires you to look at the person or object you are modeling and break it down into basic forms before adding details.

Try the following activities in your classroom:

- Print an image of a sculpture and discuss it in class for an art history component. Break down the sculpture by identifying the shapes/forms in the composition. Draw them on top of the image.

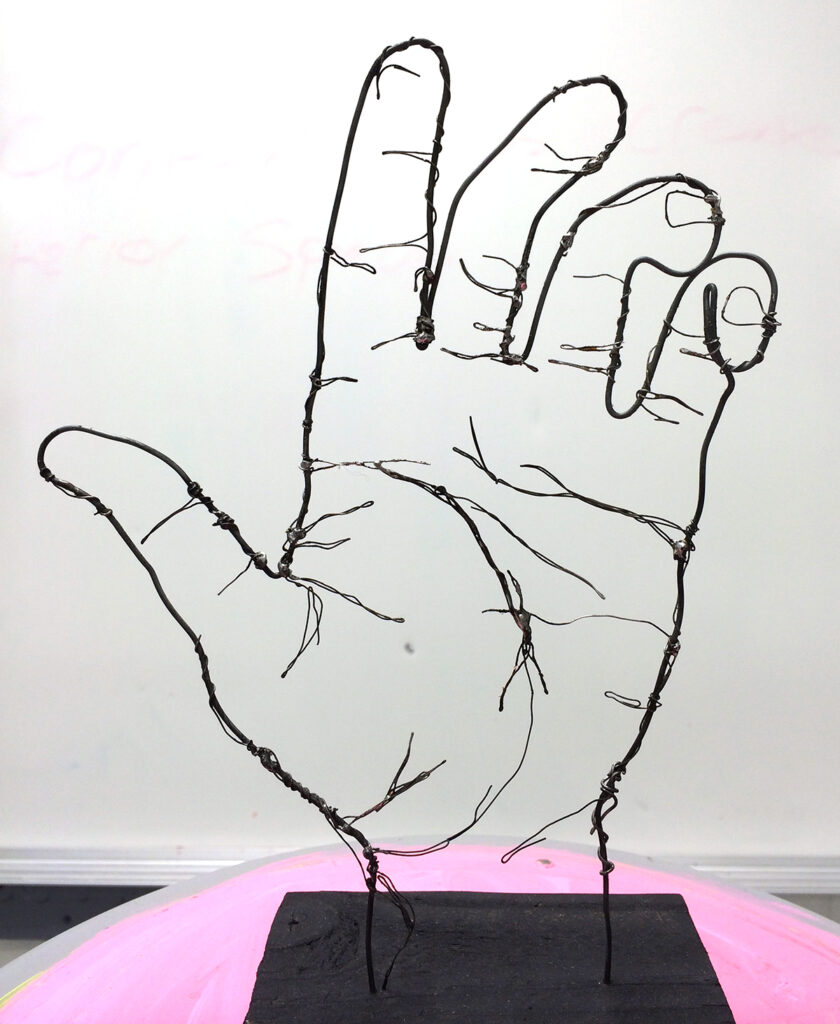

- Reference Alexander Calder’s wire pieces. Construct wire sculptures with a thin gauge wire in conjunction with a continuous contour line drawing unit.

- When teaching the parts of a landscape (foreground, midground, and background), try Debi’s lesson on environmental boxes.

3. Cultivate a deeper understanding of a subject.

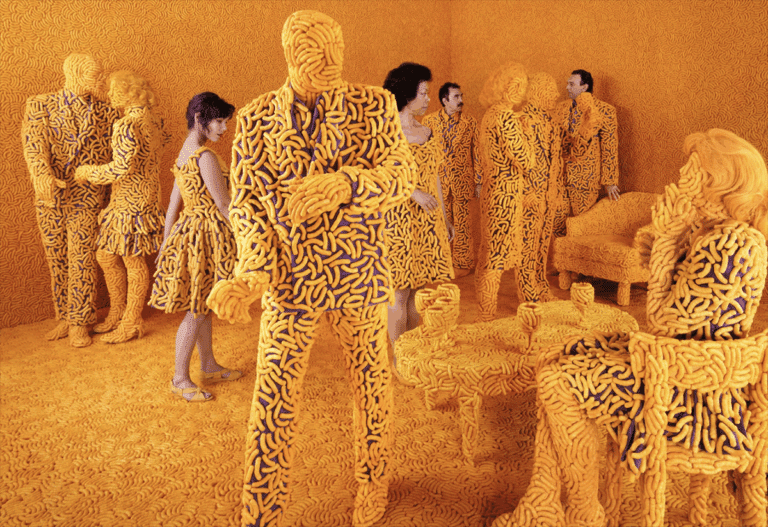

Drawing is usually one fixed perspective of a person or object. Sculpture helps you to understand your subject matter because it includes all angles. This gives you a more complete picture of a person or object. Sculptures also create shadows naturally as the piece is being formed. Observing where shadows occur on a sculpture can inform modeling on a two-dimensional plane. Being able to feel and see how deep an object is and how much space it takes up can also help students determine a realistic place to put a horizon line or cast a shadow in a drawing. Likewise, creating three-dimensional art involves an engineering aspect. How do you get the artwork to stand up and not fall over, fall apart, or droop? Understanding these elements can help students render proportion and scale more accurately in a drawing.

Do you want a quick activity for your classroom?

- Students draw a well-known sculpture for a sketchbook assignment. Be sure to provide a pre-selected list of sculptures. This incorporates art history and exposure to three-dimensional art. It will also provide students an opportunity to practice their shading and modeling techniques.

4. Consider a more conceptual approach.

In a drawing, the student determines the background and draws it. The background can be from observation or imagination. Because sculpture can be viewed from all angles, the background is often the exhibition surroundings of the sculpture. This can raise more questions around the impact of an environment on the material selection, the creation process, and how a viewer experiences an artwork. Applying these considerations to drawings will prompt more conceptual thinking.

Give these ideas from Debi a try the next time you want to challenge your students to think deeper:

- Draw on a non-traditional surface such as a scrap wood board, a found object, or a piece of fabric. Take it a step further and do something with the surface, such as building a structure, suspending the found object in a mobile, or sewing a garment from the fabric.

- As an extension activity, take an existing drawing or painting and ask, How can I make this more three-dimensional? Look at Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, a contemporary artist who merges two-dimensional painting with found objects.

- Work in small groups to design and build an installation in an area of the classroom or school.

- Add a twist on the traditional portfolio activity when students compile several drawings into an accordion book. The result is a portfolio and a sculptural piece. Students reflect on how viewing their drawings in a book versus spread out on a wall changes the experience or meaning.

5. Support fine motor skills and hand-eye coordination.

Observational drawing is all about looking at your subject matter and transferring that to your paper. Your eyes are flitting back and forth as your hand is constantly moving with the pencil. The motions are fluid. Sculpture is the same way. Your eyes are glancing back and forth between your subject matter, maquette, or preliminary sketches and your in-progress piece—all while both hands are modeling, bending, twisting, rolling, or more.

This is a fun bellringer activity to bring into your room:

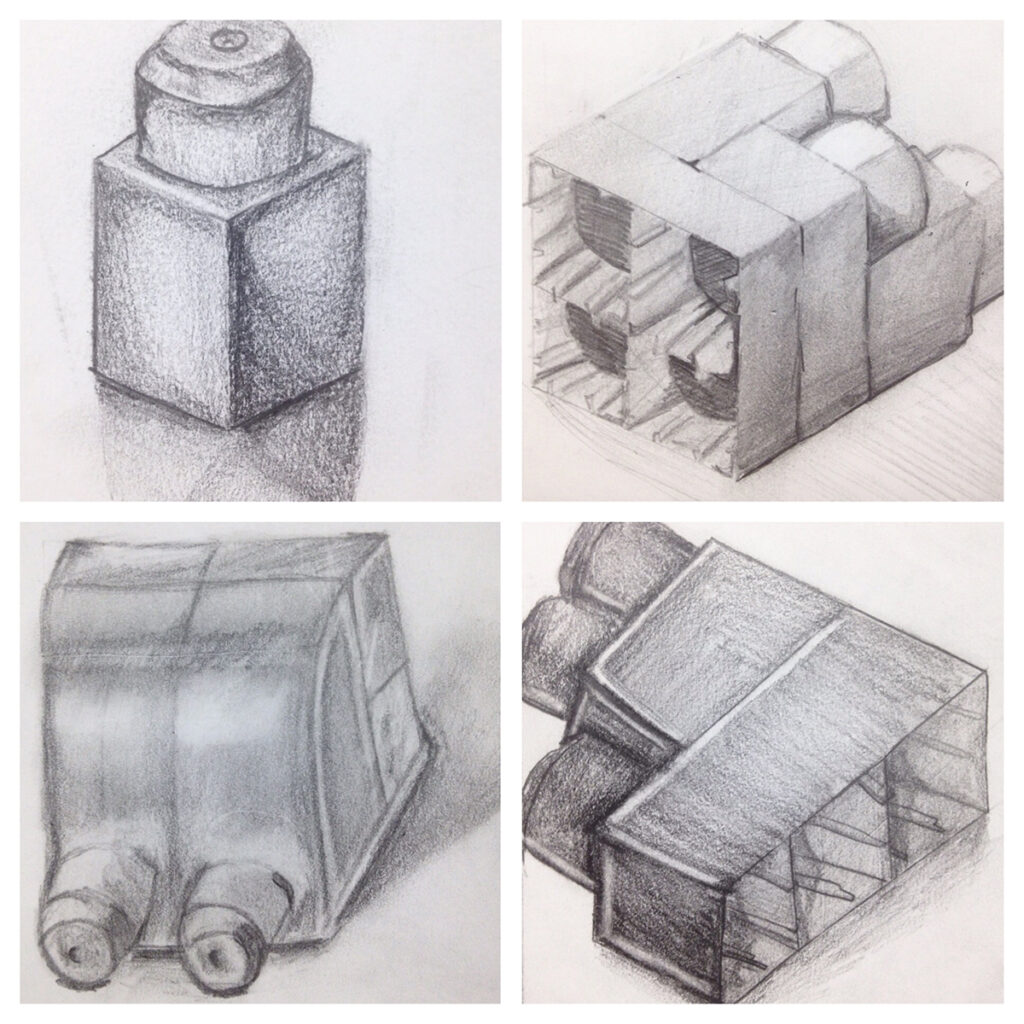

- Bring in building blocks or interlocking plastic bricks. Students construct something and then draw it from observation. Then switch things up. Students sketch a design and use the blocks to make the design a reality.

6. Develop ideas further.

For the most part, drawing can be a way to refine ideas before creating a final sculpture (or even drawing!). Look at it as formulating a plan and working out logistics before getting involved with materials. Sometimes a drawing won’t be fully realized until it’s completed as a three-dimensional piece. Imagine your student’s amazing drawing was just a plan. Stopping at the completion of a drawing could be holding a student up from developing their work or discovering a newfound love of sculpture!

Take a look at Debi’s two ideas to merge drawing and sculpture:

- Students take an existing drawing and turn the image into a sculpture. Once the sculpture is finished, go back and revise the drawing or create a new one inspired by the sculpture. How did things change or evolve with a three-dimensional understanding? Relate to the process of Henry Moore.

- Students take an existing drawing and manipulate it so it is incorporated into a sculpture. Examine the artist Robert Rauschenberg.

Sculpture does not have to be intimidating, expensive, or space-consuming. Rather, it can be a fun way to engage your students in all your classes and courses. It can also support and strengthen your students’ drawing and coordination skills. Three-dimensional art can help teach how to break down subject matter. Students gain a deeper understanding of subject matter by looking at something or creating something from multiple angles. Sculpture can also encourage a deeper thought process and the development of ideas. As you continue to plan your lessons and professional development this year, consider how to create connections between drawing and sculpture for your students.

If you are interested in adding more sculpture to your curriculum, check out the following resources to get you started:

- 7 Contemporary Sculptors Your Students Should Know

- Insider Secrets for Successful Found-Object Sculptures

- 12 Must-Have Materials For This Year’s Sculpture Projects

- Sculpture Ideas for Every Level (Ep. 075)

- Sculpture Ideas for the Art Room (Ep. 088)

- New Ideas for Fibers, Sculpture, and Metals (Ep. 191)

- Studio: Sculpture course

- Integrating Sculpture FLEX Collection found in FLEX Curriculum

- Beginning Sculpture PRO Pack found in PRO Learning

What are your favorite sculpture projects to do with your drawing, foundations, or general art classes?

How do you create connections between two and three-dimensional art with your students?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.